Sangam Literature: Exploring the Ancient Coastal Civilization and Its Harmony with Nature

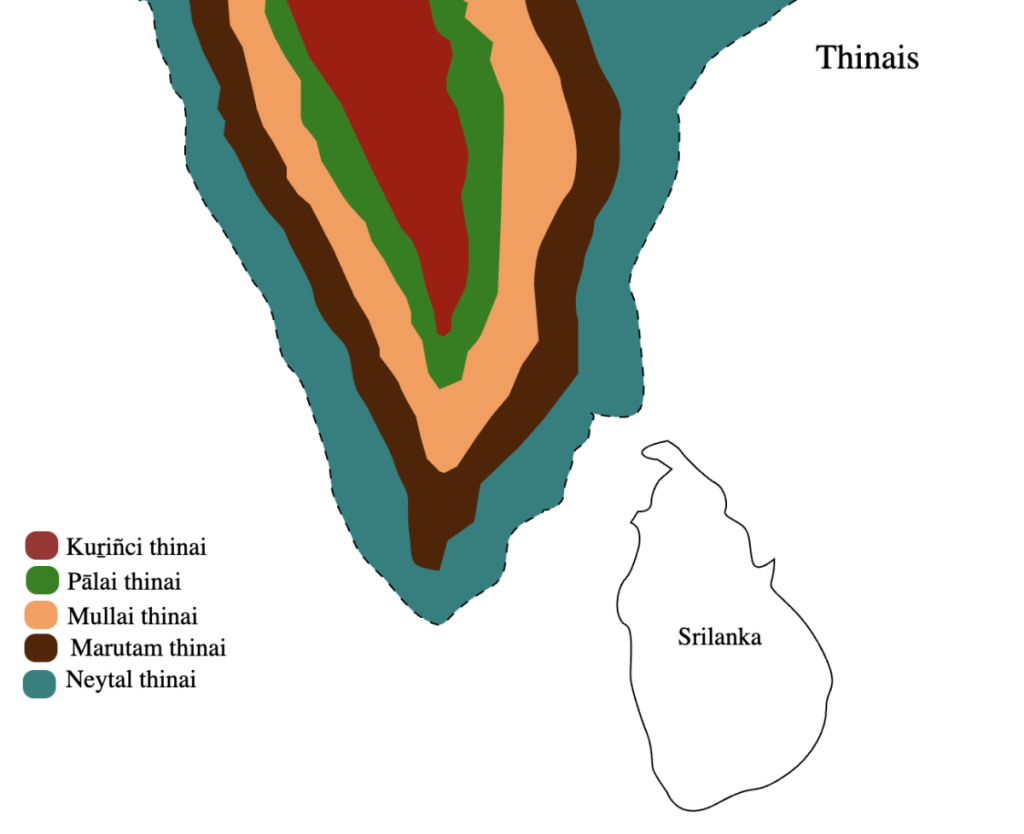

Sangam literature organises Tamil landscapes into five tinais (ecological zones): kurinji (mountains), mullai (forests), marutham (fertile agricultural plains), palai (arid zone) and neithal (coast). Each zone offers an integrated worldview, encompassing not only geography but also the food, livelihoods, customs, deities, emotional states and daily rhythms rooted in their ecological context.

This system is not a simplistic environmental categorisation, but a sophisticated lens that makes ecology inseparable from culture and effect – a model close to the modern ecological understanding of “biomes,” yet shaped by poetic, social and ethical meanings.

The world of neithal: an integrated ecosystem

Tolkappiyam describes each zone as a unique world, and for neithal, it uses the phrase “Perumanal Ulagam”, meaning a world of great sands, emphasising the distinctive, expansive, sandy landscapes of the coast. This frames the neithal as an entire ecological realm – not just in geography but as a living world of its own.

Natrinai offers a classic poetic snapshot of coastal life, referencing “Peruneer vilayul em siru nal valkai” – in big water (the vast sea) harvests, lies our small, simple life. This line beautifully captures how people’s modest, sometimes marginal, livelihoods were shaped within the abundance of the sea. The poem evokes the richness and challenges of neithal life.

This ecological world shapes the food, occupation, settlements and social organisation of coastal communities.

Together, these references from Tolkappiyam and Natrinai reinforce the idea that neithal was a world deeply interconnected, abundant, yet marked by humility and precariousness, where environment and society are tightly woven together.

This ecological imagination is central to the Sangam literary worldview and offers inspiration for reimagining urban and coastal development today.

Settlements and built forms along the coast

The architecture and settlement patterns of neithal reflect deep adaptation to coastal hazards and changing ecological conditions. Sirukudi: small, low-built houses made of palm leaves and grass are described in Sangam literature as being resilient to the region’s strong winds, storms and seasonal rains. These perishable, easily rebuilt homes allow communities to recover swiftly from coastal disasters, including cyclones and flooding.

Urban coastal centres, known as pakkam or pattinam, were characteristic of neithal regions and frequently functioned as maritime ports and trade hubs.

The naming convention is telling: “pakkam” and “pattinam” are associated with neithal towns, while “oor” is more common for Marutham (agricultural landscapes). In places where sea and agriculture interacted, there were unique transitional zones known as Neithal ul Marutham. Some historic neithal towns grew and harvested salt-tolerant crops alongside fishing, notably in the Cauvery delta at Thalainayiru, where there are accounts of fishermen cultivating salt-resistant varieties in boats, akin to the Pokkali system in Kerala, though this traditional adaptation has nearly vanished today.

This intricate blend of architecture, nomenclature and agrarian innovation underlines how neithal societies not only adapted to coastal risk but also created hybrid landscapes of resilience and productivity, deeply tuned to the dynamic edge between land and sea.

Coastal features and ecological knowledge

Sangam literature captures the complexity and richness of coastal ecological knowledge that is often ignored or misunderstood today. Perukali Nadu refers to the extensive backwater systems that were vital for neithal’s livelihoods, showcasing how freshwater (Naneer) and saltwater (Muneer) environments intersected to create unique ecotones. These intertidal areas, often incorrectly dismissed as “wastelands” in modern land, used planning, sustained fisheries, navigation and food security for centuries.

Remarkably, Sangam texts explicitly mention tsunami events (kadal kol) and submarine volcanoes (vadavai), demonstrating an ancient awareness of oceanographic phenomena that modern science has only recently begun to explore. The reverence for “ullur kadal” (“each village’s sea”) illustrates a profound place-based knowledge: a recognition that each stretch of coast is ecologically and experientially unique, and that even the same ocean is different for neighbouring villages.

This explains the diverse artisanal fisheries and local ecological expertise seen today along different Tamil coasts, such as the Coromandel, Palk Bay and Gulf of Mannar, each with its own marine species, customs and technologies.

Sophisticated spatial skills, such as triangulation (mukoona kanipu), were employed by coastal navigators, demonstrating an advanced understanding of geography, ocean currents, and spatial orientation hundreds of years before European navigation techniques gained prominence.

All these examples illustrate the depth of traditional ecological knowledge embedded in the Sangam literature, which is vastly relevant for reassessing our approach to modern coastal management and resilience.

Flora, fauna and ecology of neithal

Sangam literature richly documents the flora, fauna, and wildlife integral to the Neithal coastal landscape, portraying a sophisticated ecological and cultural knowledge system. Key plants include screw pine (thazhai), palm trees (panai), water lilies (neithal) and mangroves (neermulli), each of which is crucial for maintaining ecological balance and supporting livelihoods.

For example, the palm tree symbolises neithal itself, providing material for houses, beverages and fruits, while also serving as habitat for numerous birds. The punnai tree offers shade for drying fish and sheltering old boats, showing a practical blend of ecology and culture. Coastal birds like swans (Annam), glossy ibis (Andril), painted storks (Painkal Kokku), herons, cranes and gulls are vividly described. The poets note their habits, migrations and even monogamous bonds centuries before modern ornithology.

Sand-binding creepers, such as Adumbu (Ipomoea), play a crucial ecological role in stabilising sand dunes, which serve as nesting sites for birds and turtles. This awareness leads to careful conservation practices by fishermen, highlighting a conservation ethic rooted in ecological knowledge.

Additional features include nocturnal shark movements into backwaters (uppankali sura), sand wells (Uvaneer Keni) supplying fresh water from coastal sands, and northern winds shaping sand dunes poetically described as swaying like fine fabric (Natrinai 15). These descriptions reveal an acute awareness of coastal geomorphology and its slow, vital processes that sustain human settlements.

Today, much of this detailed knowledge is lost; modern coastal towns rarely have visible sand dunes or intact traditional ecological practices. Sangam literature, thus, offers invaluable insights into a sophisticated, ecologically embedded worldview that can inform contemporary coastal conservation and restoration efforts.

Coastal communities

The fishermen (Parathavar) and salt-makers (Alavar, Alathiyar) were central figures of this world. They built boats (naavai, vallam, thoni), fished with nets and spears, harvested salt from backwaters, and traded fish, toddy, honey and venison. Maritime merchants (umanar, umattiyar) linked coast to hinterland, weaving economies of exchange that sustained entire regions.

Coastal life in Sangam literature reveals a deeply intertwined social and moral fabric rooted in ecological sensitivity. The guilt experienced by fishermen over catching pregnant fish, as depicted in Aikurunooru, reflects a strong ethical awareness about sustaining marine life and respecting reproductive cycles.

Women’s social roles as kadal kaimpen (widows of the sea) and as dry fish sellers highlight their integral participation in both the economy and social continuum of coastal communities.

Many poems vividly describe how coastal people carefully avoided disturbing life on the shore, such as being mindful not to trample eggs laid on creepers by birds or turtles. Their abandoned carts and boats would be parked near the shade of trees, which became a nesting site for birds.

This emphasises a worldview where human and non-human lives are interconnected and respected, showcasing an ecological morality that goes beyond survival to include care and coexistence with nature. Such narratives exemplify a nuanced relationship with the environment, acknowledging ethical duties that sustain both social order and ecological balance.

Food and culinary practices

The neithal diet depicted in Sangam literature reflects a rich and varied culinary tradition closely tied to the coastal environment. Food items included fried fish, dried fish (karuvadu), fatty fish (kolumeen), and toddy derived from palm trees. There was also kulal fish cooked over akhil driftwood, underscoring the intimate connection between natural resources and cooking methods.

Social distinctions in dietary habits between Brahmins, kings and coastal communities indicate layered cultural identities and hierarchies. The Pattinapalai describes a public kitchen in Kaveripoompattinam, where warriors consumed roasted shrimp and steamed tortoise, alongside palm toddy (panai marakal) and dried fish, reflecting both every day and elite culinary practices.

The coastal identity was marked by a stereotypical “non-vegetarian smell,” a perception that persists even today. However, as portrayed in Natrinai 45, this stereotype coexists with the acknowledgment of a simple yet prosperous lifestyle, where women in the poem tell their lovers that although their place may smell due to non-vegetarian food, their small lives are rich with abundance and fulfilment.

This highlights the integration of ecological realities and cultural identity in the neithal coastal world.

Worship, rituals and cultural beliefs

Rituals, too, reflected this ecological intimacy. The sea was divine – Varunan, the guardian god, ruled over its moods. Temples faced the ocean (kadal valipadu), not turning their backs on it.

The sura kombu (shark’s horn) was worshipped as a talisman of strength, acknowledging the dangerous grace of marine creatures. Boats were placed under punnai trees and reverently garlanded. Tools of livelihood – nets, oars, sails – were sacred.

This was a spiritual ecology: an understanding that survival itself was a sacred act, and every element of nature, animate or inanimate, carried life. The poems breathe an ethic of coexistence, one that recognizes life as a continuum rather than a hierarchy.

Forgotten coastal histories: Neithal Marantha Nagaram

As one stands on Chennai’s concretised beaches today, the old neithal ulagam seems almost mythic. Modern Indian coastal cities were once vibrant neithal landscapes – a mosaic of wetlands, saltpans, mangroves and tidal creeks. The Palmyra palms that once shaped the skyline have given way to glass and concrete. Ports, power plants and “beautification” drives have erased the delicate ecotones that once sustained fisher livelihoods.

What was once neithal has now become neithal marantha nagaram – a city that has forgotten its coastal soul. The sea that once nourished life is now fenced off by ports and promenades. Fishing communities face eviction not only from industries but, ironically, from “blue flag” conservation projects that sanitise beaches for tourism.

The poetic consciousness of the coast, that sense of balance between abundance and humility, has been replaced by an urban arrogance that sees the sea as scenery, not kin.

In forgetting the neithal, cities like Chennai have lost more than their ecology; they have lost a way of seeing.

The Sangam poets remind us that the coast is not a fringe but a frontier of imagination – where earth and water, human and non-human, constantly negotiate. In the Tolkappiyam’s vision of Perumanal Ulagam, we find an ethics for our time: to live lightly, rebuild easily, respect cycles, and honour the sacredness of the ordinary.

To remember the neithal is to remember that the coast is alive: that its sand, trees, birds, and people form one breathing body. If Chennai is to survive the rising seas and the storms of our century, it must learn again from the old wisdom of the waves, from a world where even a fisherman’s guilt or a woman’s waiting carried the moral weight of the ocean.