Trump Resumes US Nuclear Testing, Sparking Global Tensions and South Asian Arms Race

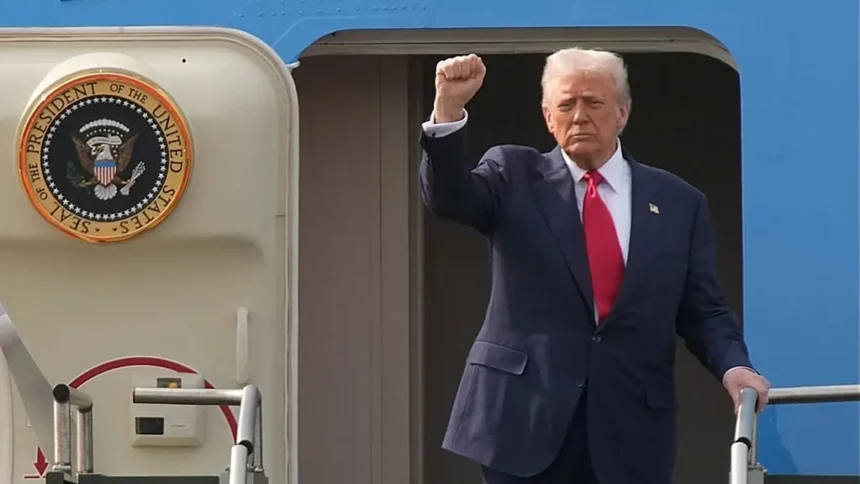

New Delhi: US President Donald Trump today announced that he has authorised the Pentagon to immediately resume the testing of nuclear weapons – 33 years after the United States conducted its last test and announced a moratorium on future testing – and put the blame on “other countries’ testing programs”:

“The United States has more Nuclear Weapons than any other country. This was accomplished, including a complete update and renovation of existing weapons, during my First Term in office. Because of the tremendous destructive power, I HATED to do it, but had no choice! Russia is second, and China is a distant third, but will be even within 5 years. Because of other countries testing programs, I have instructed the Department of War to start testing our Nuclear Weapons on an equal basis. That process will begin immediately.”

The last Chinese and Russian nuclear tests were at Lop Nor, Tibet in July 1996 and Novaya Zemlya in 1990, respectively, and neither country has resumed or threatened to resume testing. Thus, it is not clear what Trump means by ordering the ‘Department of War’ to “start testing” its nuclear weapons “on an equal basis”.

Indeed, both Russia and China, like the US, are signatories to the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (CTBT) though none of the three major nuclear weapon states has ratified it yet. Since the CTBT opened for signature in September 1996, three countries have tested nuclear weapons – India and Pakistan in 1998, and North Korea, from 2006 to 2017.

US media are linking Trump’s decision to recent Russian tests of new delivery systems for its nuclear arsenal, though the two are entirely different things. The US itself has never stopped working on its delivery systems.

Trump went public with his decision hours before his planned meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping in Seoul, which he also heralded on social media with a message: “The G2 will be convening shortly”.

The US president’s use of the ‘G2’ nomenclature suggests a fundamental shift in the American approach to power politics – one premised on the pursuit of a condominium with China, where the two major powers would jointly deal with global problems, rather than of containment.

The G2 concept was first floated by economist Fred Bergsten, former US national security adviser Zbigniew Brezinski and others around 15 years ago but has proved difficult if impossible to pursue except in short spurts.

The CTBT has not entered into force so there is no legal obstacle in the way of the US resuming nuclear testing. However, the ending of the US moratorium will almost certainly open the doors for Russia and China to test their own nuclear arsenal, both to ensure the ‘reliability’ of existing weapons and validate newer designs and concepts.

The US pushed for the CTBT following the last of its tests because it knew it had a dual advantage over Russia and China at the time: its arsenal was much larger, and it was confident of a superior ability to use computer simulations to design and ‘test’ new weapons. To the extent to which Moscow and Beijing feel the CTBT put the US in a better relative position, both of their militaries are likely to use any US explosive nuclear test as an alibi for a new series of their own tests.

India and nuclear tests

The US pursuit of the CTBT in the 1990s, especially under the Clinton administration, was also aimed at closing the door on undeclared nuclear weapon states like India and Pakistan before they had the chance to conduct explosive tests.

In response, India rushed to conduct a series of tests in May 1998 before announcing a testing moratorium, followed by Pakistan, and both countries were condemned by the UN Security Council at the time. The US imposed a series of sanctions on India that year but under the George W. Bush administration began a process of relaxation that culminated in the US committing itself in 2005 to the pursuit of full nuclear cooperation with India provided the latter stuck to its moratorium on nuclear tests, agreed to separate its military and civilian nuclear programmes and place the latter under International Atomic Energy Agency safeguards.

When Indian negotiators began discussions on how the 2005 nuclear agreement would be operationalised, they found the US side looking for ways to turn India’s voluntary moratorium on nuclear testing into a legally binding commitment. Indian officials parried that attempt but the US Congress and administration insisted on inserting a clause (Article 14) in the ‘123 Agreement’ of 2007 governing nuclear commerce with India that would allow Washington to not only terminate the agreement after giving notice of its reasons (presumably an Indian nuclear test) but also seek the return of any equipment or material it had supplied.

However, India’s negotiators successfully managed to dilute these US demands – widely seen as a deal killer – by predicating the return of any US equipment on Washington first ensuring the “uninterrupted operation” of Indian nuclear reactors in the event of any Indian nuclear weapons test.

More importantly, in the context of Trump’s latest announcement ordering the resumption of nuclear testing, Article 14.2 opens a door for India to cite its “changed security environment” as the trigger for any new nuclear test:

“[The US and India] further agree to take into account whether the circumstances that may lead to termination or cessation resulted from a Party’s serious concern about a changed security environment or as a response to similar actions by other States which could impact national security.”

In addition, India’s negotiating team also implicitly firewalled India’s strategic programme by having the 123 Agreement note (Article 2.4) that the “purpose of this Agreement is to provide for peaceful nuclear cooperation and not to affect the unsafeguarded nuclear activities of either Party.”

“Accordingly, nothing in this Agreement shall be interpreted as affecting the rights of the Parties to use for their own purposes nuclear material, non-nuclear material, equipment, components, information or technology produced, acquired or developed by them independent of any nuclear material, non-nuclear material, equipment, components, information or technology transferred to them pursuant to this Agreement. This Agreement shall be implemented in a manner so as not to hinder or otherwise interfere with any other activities involving the use of nuclear material, non-nuclear material, equipment, components, information or technology and military nuclear facilities produced, acquired or developed by them independent of this Agreement for their own purposes.”

At the time of the negotiations there was a group of nuclear scientists and strategic analysts led by PK Iyengar who wanted India to not just keep the option of testing nuclear weapons – which the 123 agreement did in a roundabout fashion – but to actually go ahead and test, especially a thermonuclear bomb, which they claimed had not performed as expected during the May 1998 tests at Pokharan.

Atomic scientist R. Chidambaram, who was the principal scientific adviser to the Manmohan Singh government at the time, denied this and went on record to state there was no military reason for India to test any further given the successful conclusion of the Pokharan II round.

However, the actual resumption of US nuclear testing will likely fuel a fresh debate in India on this question and possibly pave the way for India to resume testing. Pakistan, too, would then follow.