16 Rare Snakes Detected: Mumbai Airport Intercepts Unusual Cargo from Thailand

Unveiling the Exotic Cargo – Seizure of 16 Live Snakes at Mumbai Airport

Introduction: Wildlife Smuggling Unfolds Again

On a humid Sunday morning in June 2025, customs officers stationed at Mumbai’s Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj International Airport intercepted a returning passenger from Thailand. Hidden within his luggage lay a bizarre and unsettling cargo—16 live snakes, wriggling and sealed in plastic containers, destined to fuel the underground exotic pet trade in India. This marked the third such seizure this month alone, intensifying concerns over an escalating pattern of wildlife smuggling via the Thailand-India route.

Operation Wriggling Cargo

The seizure was executed as part of a routine inspection when customs officers, trained to detect irregularities in passenger movement, noticed suspicious packaging in the baggage. Upon detailed examination, they discovered:

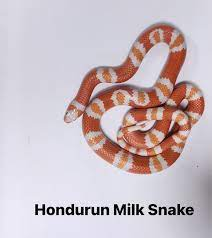

- Garter snakes – Commonly bred for ornamental purposes

- Rhino rat snakes – A visually striking reptile often found in black markets

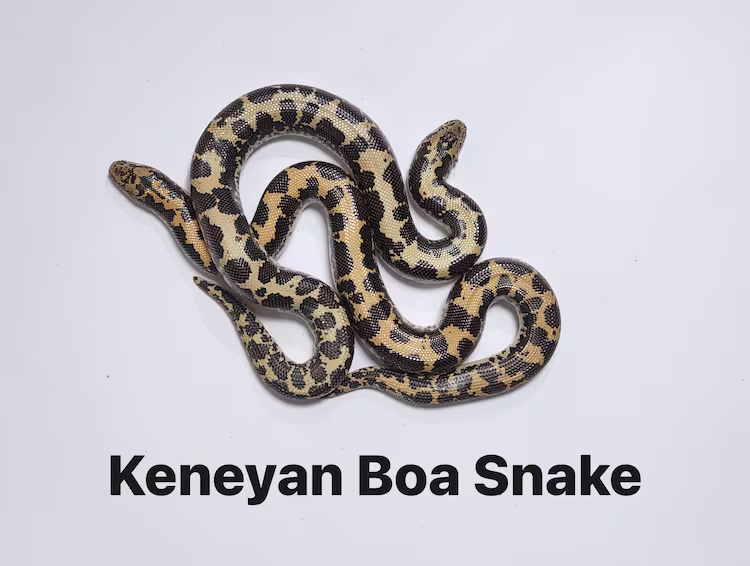

- Kenyan sand boas – A non-venomous species valued in illegal pet circuits

According to preliminary forensic veterinary assessments conducted by the Wildlife Crime Control Bureau (WCCB), all the species were in stable condition, though signs of dehydration and stress were evident.

Profile of the Perpetrator

The detained individual, whose identity remains undisclosed pending investigation, was apprehended under the Wildlife Protection Act, 1972, and provisions of the Customs Act, 1962. He is believed to be a mule for a larger international trafficking ring operating between Southeast Asia and India.

Customs issued a formal press release confirming:

“Customs officers foiled yet another wildlife smuggling attempt. 16 live snakes were seized from a passenger returning from Thailand. Further investigation is underway.”

Why Snakes? The Demand in Exotic Pet Markets

Non-native snakes, especially those perceived as harmless or ornamental, are increasingly trafficked due to high demand in India’s urban exotic pet markets. While the reptiles seized were largely non-venomous or had venom too weak to harm humans, their possession, trade, and transport without permits are illegal under Indian law.

Experts say buyers range from private collectors to upscale spas and resorts, where animals are kept as status symbols or part of luxury aesthetics. The creatures’ silence, compact size, and low maintenance requirements make them lucrative commodities.

Repeat Incidents: Alarming Pattern in June 2025

This is not an isolated case. In early June:

- Dozens of venomous vipers were seized from another passenger from Thailand

- Days later, another arrest followed involving 100 exotic creatures, including:

- Lizards

- Tree-climbing possums

- Rare sunbirds

Such repeated infractions within weeks indicate an organized trafficking network exploiting weak monitoring mechanisms and rising demand.

TRAFFIC Sounds the Alarm

TRAFFIC, a global wildlife trade monitoring organization, has classified this trend as “very troubling” and noted a surge in seizures involving:

- Live reptiles

- Amphibians

- Small mammals and exotic birds

Their internal data reveals:

“Over 7,000 animals—dead and alive—have been seized on the Thailand-India air route in the last 3.5 years.”

This staggering number represents not only a failure of border surveillance but also a loophole in transnational enforcement cooperation.

Challenges in Enforcement

Authorities acknowledge that tackling wildlife smuggling through commercial airlines poses multifaceted challenges:

- Limited x-ray detection accuracy for non-metallic life forms

- The absence of real-time species recognition AI at entry ports

- Overworked staff unable to manually inspect every passenger from high-risk regions

Despite growing awareness, India’s 18 major airports have only 6 fully operational wildlife detection units.

India’s Legal Framework and Gaps

The smuggling of these species violates:

- Sections 49B and 51 of the Wildlife Protection Act

- CITES regulations (India is a signatory to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species)

- Customs-related offenses under Section 111 of the Customs Act

However, enforcement often suffers due to:

- Lack of trained personnel at ports

- Weak coordination between customs, WCCB, and foreign wildlife bureaus

- No centralized digital registry of intercepted species or offenders

Mapping the Trafficking Pipeline – From Thai Jungles to Indian Metros

A Transnational Smuggling Web

As investigators delve deeper into the Mumbai snake seizure case, a larger and more ominous picture emerges—a coordinated trafficking route connecting Thailand’s illegal reptile markets with India’s underground exotic pet trade. Intelligence gathered from wildlife enforcement agencies indicates that Mumbai, Kolkata, and Chennai serve as primary Indian gateways for smuggled wildlife arriving from Southeast Asia.

Source Locations in Thailand

Thailand, known for its lush forests and biodiversity, is also home to several unregulated exotic animal markets. The snakes in the Mumbai case are believed to have originated from:

- Chatuchak Market (Bangkok) – A known hub for endangered species

- Northeastern provinces – Where wild captures are common

- Backyard breeding farms – Operating without CITES licenses

Traders procure or breed these reptiles and sell them to international buyers or couriers for export. Despite crackdowns, corruption and under-enforcement allow the markets to flourish.

Trafficker Coordination and Air Transport

The smuggling method typically follows this blueprint:

- Recruitment of couriers (often Indian nationals visiting Thailand)

- Packaging reptiles in sealed, oxygenated containers

- Concealment in luggage, wrapped in clothes or hidden within electronic appliances

- Bribery or evasion of weak inspection stations at departure airports

Flights from Bangkok’s Suvarnabhumi Airport to Indian cities are frequent and inexpensive, making them ideal trafficking corridors.

Arrival in India – Entry Points and Loopholes

Once in India, trafficked animals enter via airports where detection is lax. Primary hotspots include:

- Mumbai Airport – With a history of wildlife seizures dating back a decade

- Chennai and Kolkata Airports – Entry points for exotic birds and reptiles

- Delhi Airport – Occasionally used for rare mammals and insects

Couriers often pass through the green channel, banking on low scrutiny. Only 10–20% of luggage from high-risk zones undergo manual checks.

Distribution Within India

Upon arrival, the animals are distributed through a loose but organized network of:

- Private breeders and collectors in metros like Bengaluru, Delhi, Pune

- Pet shop fronts operating illegally in cities and online

- Social media black markets (Telegram, WhatsApp groups, Instagram DMs)

The animals may be sold within hours—often before law enforcement can trace their movement post-seizure.

Data from the WCCB and TRAFFIC shows:

- Over 62% of smuggled reptiles end up in Mumbai, Bengaluru, and Hyderabad

- About 30% perish during transport due to poor handling and stress

- Nearly 45% of arrests involve repeat offenders or linked couriers

Smuggling via Courier Services and Parcel Post

Besides air transport by individuals, wildlife traffickers increasingly use:

- Courier shipments falsely declared as ornamental goods

- Postal parcels routed through NE India and border states

Customs officials have intercepted hundreds of reptiles in boxes labeled as “home décor” or “electronic spares.”

Human Trafficking Parallels: The Courier Chain

In many cases, couriers involved in smuggling are unaware of the exact contents or biological risks. They’re paid fixed sums—between ₹10,000 to ₹50,000 per trip. Organized rackets rotate these couriers to avoid detection patterns.

One WCCB investigator said:

“We are not just dealing with wildlife crime. We are also up against sophisticated courier networks, like those used in narcotics.”

Lack of Coordination Between India and Thailand

While both countries are signatories to CITES, coordination gaps include:

- No real-time data sharing on seizures or suspects

- No joint investigation units or task forces

- Rare cross-border prosecutions or extraditions

Thailand’s environment ministry occasionally issues advisories, but few translate into actionable enforcement.

The Role of Airlines and Airport Security

Most airlines are yet to train their ground staff to:

- Detect live animal concealment techniques

- Report suspicious baggage declarations

- Coordinate with WCCB when alerts are triggered

CISF personnel stationed at Indian airports often lack exposure to wildlife crime scenarios.

Inside India’s Black Markets – Digital Trafficking, Urban Breeding, and Legal Grey Zones

Introduction: The Indian Underground Pet Industry

While the customs seizure in Mumbai revealed the trafficking pipeline from Thailand, what happens once these creatures enter Indian soil is a more cryptic and deeply embedded issue. Exotic animals, especially snakes, are quietly traded across Indian cities through a network that merges dark web operations, encrypted messaging apps, breeder circles, and unregulated exotic pet expos.

This part explores the complex and elusive world of illegal wildlife sales within India.

Digital Smuggling 2.0: From Telegram to Instagram

Gone are the days of shady dealers in dark alleys. Today’s wildlife black market thrives in:

- Telegram groups with invite-only access

- WhatsApp broadcasts using coded terms

- Instagram pages disguised as reptile enthusiasts

- Facebook marketplace clones hosted on private servers

Dealers operate under pseudonyms and post:

- Photos of snakes with no price (DM for rate)

- Codes like “G-SB” for Garter Snake Boa

- Emojis as availability indicators (e.g., 🐍 = ready, 🛑 = sold)

These digital platforms offer anonymity and global reach. Payments are often done via:

- UPI handles registered to fake IDs

- Cryptocurrency wallets

- Cash-on-delivery via intermediaries

Offline Channels: Expos and Pet Circles

India’s metro cities—Delhi, Bengaluru, Mumbai, Pune, Hyderabad—regularly host underground exotic pet expos that masquerade as hobbyist fairs. Under the guise of “educational reptile awareness,” animals are displayed and discreetly sold.

Buyers range from:

- Film and TV production houses (for props)

- Upper-class hobbyists

- Social media influencers seeking content

- Private breeders looking to cross-breed for rarity

In 2023, an NDTV sting operation exposed one such fair in Hyderabad where:

- 19 species of exotic animals were openly displayed

- Prices ranged from ₹15,000 to ₹2.5 lakh

- Foreign handlers were present, suggesting cross-border links

Urban Breeding Farms: The Domestic Supply Chain

Besides imports, some traffickers have now turned to in-house breeding. In suburbs like:

- Bawana (Delhi)

- Hadapsar (Pune)

- Peenya (Bengaluru)

Investigations found dozens of houses doubling as snake farms. These urban setups:

- Use modified fish tanks and UV lamps

- Employ untrained handlers

- Have no veterinary supervision

These farms breed for quantity, not quality—leading to poor animal health and high mortality.

The Pricing Game: What an Exotic Snake Costs in India

| Species | Street Price (₹) | Black Market Price (₹) |

|---|---|---|

| Kenyan Sand Boa | 10,000–15,000 | 25,000–30,000 |

| Rhino Rat Snake | 30,000 | 50,000+ |

| Garter Snake (rare) | 8,000–12,000 | 20,000–25,000 |

| Ball Python (albino) | 50,000 | 1–1.5 lakh |

These prices exclude transportation, vet concealment, and cage charges—bringing total costs to often triple the MRP.

Legal Grey Zones: The Loopholes Enabling Crime

Despite the Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972, and India’s commitment to CITES, there exists a legal grey zone:

- Non-native species not listed under Schedules are unprotected

- Reptiles and amphibians often don’t have specific enforcement guidelines

- Poorly maintained CITES import/export databases

For example, the Kenyan Sand Boa, while illegal to trade, is not explicitly listed in enforcement manuals, making prosecutions difficult.

Case Study: The Bengaluru Snake Ring Bust (2022)

In one of India’s largest urban snake trafficking crackdowns, authorities raided a home in Whitefield, Bengaluru and recovered:

- 23 snakes

- 15 turtle species

- 9 rare amphibians

The perpetrators were released on bail within 72 hours because:

- Many species lacked protection status in Indian law

- Seized animals were not venomous or endangered

- Legal definitions did not cover urban exotic pet abuse

Veterinary Complicity and Forged Certificates

In many cases, buyers are issued forged health certificates from complicit veterinarians. These include:

- Fake quarantine clearance

- Forged municipal approvals

- Non-existent lab reports certifying the animal as safe

Such documentation makes enforcement harder, especially if owners claim ignorance.

The Hidden Fallout – Ecological and Public Health Risks of Snake Trafficking

Introduction: Beneath the Surface of Exotic Trade

While the economic and enforcement dimensions of snake trafficking are vast, a deeper consequence lies in its hidden impacts—on ecosystems, native species, and public health. The underground movement of exotic snakes into urban and rural Indian environments poses a triple threat: ecological imbalance, outbreak of zoonotic diseases, and erosion of community-level biodiversity.

Ecological Disruption: Invasive Species and Habitat Competition

Many exotic reptiles released or escaped into the wild pose a serious invasive threat to India’s native ecosystem. Species like the Rhino Rat Snake and Garter Snake, which are non-native, compete directly with indigenous snakes for:

- Prey species (frogs, small rodents, birds)

- Microhabitats (bamboo groves, abandoned fields)

- Reproductive territory

A 2023 study by the Indian Institute of Ecology and Wildlife Sciences found that invasive snakes released in Maharashtra’s Konkan belt outcompeted native vine snakes in 43% of observed zones.

Additionally, these non-native snakes can:

- Introduce foreign parasites and pathogens

- Disrupt local food chains

- Cause species extinction via predation or interbreeding

Case Example: Kerala’s Silent Invaders

In 2022, forest officials in Thrissur district reported an abnormally high population of Boa constrictors, traced back to an illegal breeder who released them during a raid. Over 14 native species saw declining numbers in the next year.

Zoonotic Diseases: A Public Health Blind Spot

One of the most ignored risks of snake smuggling is its role in zoonotic disease transmission—infections that jump from animals to humans. Exotic snakes may carry:

- Salmonella bacteria – causing foodborne illnesses

- Arenaviruses and Paramyxoviruses – deadly to humans

- Novel parasites – capable of mutating in Indian environments

These pathogens can be passed to:

- Handlers and owners through direct contact

- Household members through contaminated cages or surfaces

- Local species through fecal matter and bites

Experts from the National Institute of Virology warn that:

“Just one infected reptile introduced into a dense urban area could trigger a new viral outbreak. The lack of vet quarantine or bio-control makes this highly likely.”

Case Study: Pune Gastroenteritis Cluster (2021)

In July 2021, a cluster of gastroenteritis cases in Pune was linked to a family illegally housing Garter Snakes. The snakes carried high loads of Salmonella, traced via stool samples. The local health department issued warnings but lacked protocols for reptile-borne illness containment.

Veterinary Voids and Lack of Reporting

Veterinary care for reptiles is largely absent in India. Even in Tier-1 cities:

- Less than 3% of registered vets are trained in herpetology

- There are no national reptile disease reporting systems

- Exotic snake deaths are not required to be reported unless endangered species are involved

This makes early warning, containment, and treatment of zoonotic spillovers virtually impossible.

Risks to Native Biodiversity and Cultural Practices

India’s forest-dwelling communities and rural populations often coexist with native snake populations—sometimes integrating them into:

- Local medicine practices

- Rituals and temple beliefs (e.g., Naga Panchami)

- Pest control roles in agriculture

The influx of non-native species threatens these delicate human-wildlife relationships. If aggressive or venomous species are released:

- Traditional snake-charmers face new risks

- Villagers may resort to indiscriminate killing of all snakes

- Cultural faith in co-existence is undermined

Climate Change and Trafficking Synergy

Climate change is expanding the habitable zones for many tropical reptiles. Areas previously unsuitable for species like the Ball Python or Kenyan Sand Boa are now viable habitats due to:

- Warmer winters

- Extended rainy seasons

- Shifting vegetation patterns

Traffickers are exploiting this by targeting emerging zones like:

- Madhya Pradesh’s Satpura forests

- Himachal Pradesh’s lower valleys

The illegal trade in exotic snakes is not just a conservation or legal issue—it is a biosecurity threat. From zoonotic disease emergence to ecosystem destabilization, the fallout of unchecked trafficking is already unfolding across India.

Legal Remedies, Enforcement Innovations, and Global Cooperation

Introduction: Turning the Tide on Trafficking

As India grapples with the expanding crisis of exotic snake trafficking, a clear realization has emerged—piecemeal enforcement and ad hoc raids will not suffice. What’s needed is legal reform, multi-agency coordination, international cooperation, and technological innovation. This part explores the tools, frameworks, and emerging best practices being deployed or proposed to combat the illegal wildlife trade more effectively.

India’s Wildlife Laws: Strengths and Gaps

India’s primary legal shield against wildlife trafficking is the Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972. It criminalizes trade, possession, and transport of protected species. However:

- The Act focuses primarily on native species

- Non-native exotic animals not listed under Indian Schedules are often left out

- Enforcement depends heavily on species classification and paperwork

To address this, in 2022, an amendment was passed that introduced:

- Regulation of exotic species through permits

- Mandatory declaration of exotic pets

- Expanded role of the Directorate of Wildlife Preservation

However, its implementation is still in its infancy.

Role of the Wildlife Crime Control Bureau (WCCB)

The WCCB, under the Ministry of Environment, is the nodal agency for wildlife crime intelligence. Its roles include:

- Maintaining a wildlife crime database

- Coordinating inter-state raids

- Liaising with customs and INTERPOL

Key challenges it faces:

- Understaffing (only ~100 officers nationwide)

- Lack of real-time data sharing with customs and airport security

- Limited access to advanced tech (e.g., cargo scanners, DNA forensics)

Technology Innovations in Wildlife Crime Enforcement

Several promising tools are being explored:

- AI-Powered Scanning: Trials at Bengaluru and Delhi airports use AI to detect irregularities in baggage images

- Blockchain for CITES Permits: Ensures authenticity of wildlife trade paperwork

- DNA Barcoding and Reptile Genome Banks: Helps identify species in real-time

- eDetection Apps: A mobile app by WCCB allows citizens to report suspected wildlife crime anonymously

International Protocols and India’s Role

India is a signatory to major treaties such as:

- CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species)

- Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD)

- INTERPOL’s Environmental Crime Programme

Through these, India:

- Shares seizure data internationally

- Participates in Operation Thunder (global wildlife enforcement action)

- Cooperates with ASEAN-WEN (Wildlife Enforcement Network)

Yet India has not yet established:

- Permanent transboundary intelligence-sharing cells

- Joint operations task forces with high-risk nations like Thailand or Myanmar

Case Study: Operation WILDNET (2023)

In 2023, WCCB and Interpol launched a sting operation targeting online wildlife trafficking. Key outcomes:

- 187 accounts tracked across Instagram and Telegram

- 49 arrests in Mumbai, Hyderabad, and Kochi

- Seizure of 77 reptiles and 13 amphibians

This highlighted the digital-first nature of current wildlife crimes—and the need for cybercrime units trained in ecological crime.

Judiciary and Penalties: The Weak Link

Even when arrests are made, convictions are rare. Reasons include:

- Poorly documented seizure protocols

- Lack of forensic evidence

- Low fines (₹25,000–₹50,000)

Recent court suggestions include:

- Fast-track wildlife crime benches

- Wildlife-specific training for prosecutors and magistrates

- Enhanced penalties for repeated or large-scale smuggling

Community Engagement and Whistleblower Networks

Communities are vital to enforcement. Programs that have shown promise:

- Wildlife Watch Volunteers in Assam and Maharashtra

- Cash incentives for reporting illegal pet trade

- School-based awareness campaigns in Kerala and Tamil Nadu

Yet more integration is needed at the panchayat and municipality level.

Policy Proposals and Roadmap Ahead

Experts recommend:

- Comprehensive Exotic Wildlife Bill to fill legal gaps

- Mandatory CITES registry for all exotic imports

- Airline and cargo operator compliance training

- Creation of a National Exotic Species Control Authority (NESCA)

Such a body could:

- Maintain real-time exotic species registries

- Issue digital clearance certificates

- Lead habitat restoration for seized species

While India’s enforcement of native wildlife laws has evolved over decades, the rise in exotic snake trafficking calls for a 21st-century overhaul. Technology, legal innovation, global cooperation, and public participation must converge to stop the underground reptile economy from destroying biodiversity and endangering public health.

Also Read : Bengaluru Woman Found Dead in Garbage Truck: 5 Key Facts About Live-In Partner Case