Panjab 95 Director Reveals 7 Shocking Moments with Censor Board: A Kafkaesque Ordeal

Panjab 95 director reveals 7 shocking moments with the Indian censor board, describing the approval process as a Kafkaesque ordeal that tested creative freedom.

The Long Silence — A Filmmaker’s Kafkaesque Struggle Against the System

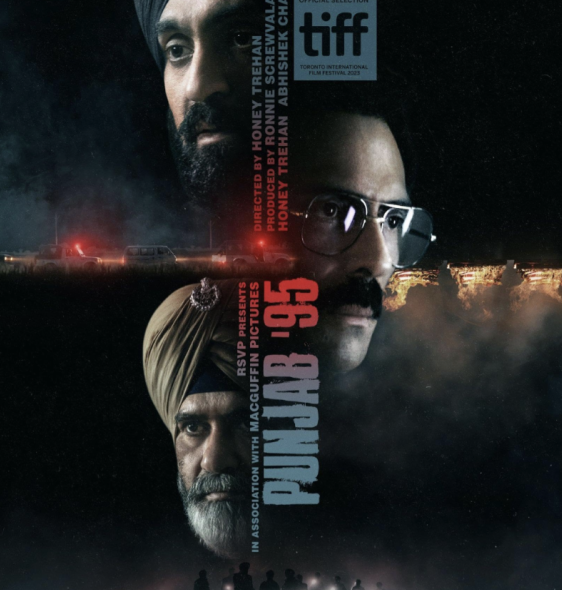

In what has evolved into one of the most high-profile instances of artistic suppression in Indian cinema, director Honey Trehan’s film Panjab ‘95 remains unreleased more than three years after completion, owing to an increasingly convoluted and obstructive battle with the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC). Trehan, a respected name in the industry and the creative force behind the film, has publicly detailed his ordeal — one that has drawn comparisons to Kafka’s surreal bureaucratic nightmares.

Originally slated for a world premiere at the 2023 Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF), Panjab ‘95 was withdrawn at the last minute, sending shockwaves across the global film community. In an in-depth, 90-minute conversation, Trehan opened up about the unrelenting censorship, the bureaucratic absurdities, and the emotional toll of seeing his vision buried under escalating demands for cuts.

The film — based on the life of human rights activist Jaswant Singh Khalra — tackles some of the darkest episodes from Punjab’s violent decade during the 1980s and 1990s. Khalra, a soft-spoken banker turned activist, uncovered a horrifying pattern of disappearances and extrajudicial killings by the Punjab Police, eventually leading to his own abduction and murder. The narrative, steeped in truth and grounded in documented history, is what has seemingly alarmed the censors.

“The film was given 21 cuts when we first applied for certification,” Trehan recalls. “We asked for reasons — there was no response. We had to go to the Bombay High Court because that was our only recourse.” What followed was a prolonged legal standoff — where the CBFC’s legal counsel was changed multiple times, hearings were indefinitely postponed, and the filmmaker was left chasing an elusive verdict.

Trehan recounts an especially surreal moment when the fourth CBFC lawyer, upon finally viewing the film, declared in open court that he had trouble sleeping after watching it. This subjective, emotionally charged reaction was then used as justification to argue that the film could provoke “militant sentiment” and cause a potential law and order situation. The judge, unimpressed, asked the counsel to identify even a single scene that incited separatism. None could be presented.

As the court proceedings progressed toward what seemed like a favorable judgment, the matter took an unexpected turn. The CBFC and the Information & Broadcasting Ministry allegedly pressured the producers behind the scenes, proposing a compromise: withdraw the case, make the cuts, and get certified. “Ronnie Screwvala, the producer, called and said: ‘We are not fighting this anymore.’ It was devastating,” Trehan says.

What followed was nothing short of Kafkaesque: 21 cuts became 37, then 45, and eventually ballooned to 85. “At one point, I’d lost my mind,” Trehan says. “This is arm-twisting. It’s not about cuts anymore — it’s about breaking your spirit.”

Trehan’s refusal to surrender was shared by lead actor Diljit Dosanjh, who declared he would remove his name from the credits if the film was released in its mutilated form. “Even Diljit said he will not be associated with a version that has lost its truth,” Trehan shares.

Censorship, Bureaucracy, and the Politics of Fear in Indian Cinema

The experience Trehan narrates reads less like the journey of a filmmaker and more like a slow descent into the darker corners of India’s state-censorship machinery. From the very beginning, Trehan and his team were met with obstruction. “The first time we submitted Panjab ‘95 to the CBFC, they stopped the screening after 30 minutes and asked us to apply to the Punjabi films’ board instead,” Trehan says. This, despite the film being multilingual — featuring significant Hindi dialogue and a pan-Indian cast.

Subsequent screenings with the Revising Committee didn’t improve matters. The Committee rejected the film’s narrative premise, with one member reportedly saying, “None of this ever happened in India.” In response, Trehan submitted a comprehensive 1,800-page research dossier composed of official court records and historical documents. The members’ response? “Who is going to read so much?” they asked.

“We even highlighted specific segments related to each of the 21 objections,” Trehan explains. “And yet, the committee watched the film again and returned with more observations.” These included bizarre suggestions such as replacing historically accurate place names — like changing Trilokpuri to “Khanpuri.”

Even after complying with initial demands, the number of cuts kept rising. The final tally reached a staggering 127 cuts. “This was not editing. This was dismemberment,” Trehan says. “At one point, someone at the CBFC asked Ronnie Screwvala, ‘Why don’t you write off this film?’”

Trehan also details how, even after multiple viewings and compliance, the CBFC Chairperson had still not watched the film. In one instance, a peon informed the team waiting outside that “Sahab has left for the day. He will communicate via email.” That communication never came.

Amidst this chaos, Trehan sought validation elsewhere. He screened the film for the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee (SGPC), the Akal Takht, and even Jaswant Singh Khalra’s lawyers. All of them reportedly endorsed the film, moved by its emotional power and factual grounding. “I kept thinking — am I missing something? Am I blind to some harm in my own work? But no one could give me a credible reason to justify these objections,” Trehan says.

Trehan calls the CBFC a compromised institution — a gatekeeper of narratives that serve political interests. “Their job is not to regulate cinema anymore — it is to affirm state propaganda,” he states bluntly. “You want to make 50 films that praise your government, go ahead. But at least let one film from the other side tell the truth.”

His most poignant grievance is not with individuals but with a system built to stifle dissent. “Some CBFC members privately told me they loved the film, but said, ‘In bureaucracy, our hands are tied.’ This duality is painful,” Trehan adds.

One of the few bright spots in this exhausting journey was the support Trehan received from the Punjab Police itself — despite the fact that the film portrays historical wrongdoing by their institution. “When I told a DSP in Tarn Taran that the film was about Jaswant Singh Khalra, he said, ‘Then the villains must be the Punjab Police?’ I didn’t say anything. He then said, ‘He was too great a man. His martyrdom is bigger than any of us. I’m glad you’re making a film about him.’”

To Trehan, this acknowledgment — from within the very system his film critiques — holds deeper value than any official certificate. But without that certificate, Panjab ‘95 remains unreleased, its voice silenced by an administration more afraid of history than fiction.

The filmmaker now stands at a crossroads. The battle may have drained him, but his resolve remains unbroken. “I’ve made it clear,” Trehan says. “If the film is released with 127 cuts, I will not attach my name to it. That’s not my film. That’s their Frankenstein.”

Anatomy of a Silencing — The Legal Vacuum After FCAT’s Abolition

One of the most critical yet underreported dimensions of the Panjab ‘95 censorship saga is the absence of a key institutional safeguard: the Film Certification Appellate Tribunal (FCAT). In 2021, the Government of India abolished the FCAT, effectively leaving filmmakers without a structured legal recourse if they disagreed with CBFC decisions. For Trehan, this wasn’t merely an administrative detail — it was the collapse of an essential buffer between creative expression and political interference.

“We used to have a process. If the CBFC asked for unreasonable cuts, you could go to the FCAT and argue your case before a balanced, semi-judicial body,” Trehan explains. “Now, all you can do is go to the High Court — a lengthy, expensive, and emotionally draining process.”

The removal of FCAT was framed by the government as part of its effort to streamline tribunals and reduce bureaucracy. However, to many in the film industry, it signaled something far more troubling: the consolidation of control over cinematic narratives. Without the FCAT, the CBFC became both judge and executioner, and filmmakers were left pleading before overburdened courts or capitulating to arbitrary censorship.

In Trehan’s case, the court battle did offer some hope. But the CBFC’s approach within the legal proceedings betrayed the spirit of open adjudication. Counsel after counsel appeared unprepared. Arguments were based not on facts but assumptions. The turning point came when a CBFC lawyer declared the film had kept him awake at night — not because of violence or incitement, but its emotional impact. “How can the emotional strength of a film be grounds for censorship?” Trehan asks. “By that logic, every great work of art is dangerous.”

Even the judiciary seemed baffled. When the CBFC admitted that objections were coordinated with the Ministry of Information & Broadcasting, the judge remarked: “What’s the point of having the CBFC as an autonomous body then?”

Legal scholars have weighed in on the implications of FCAT’s abolition. “It’s like removing the right to appeal from a court verdict,” says media law expert Nandita Roy. “You’ve made it prohibitively difficult for a filmmaker to assert their right to free expression.”

The result? A chilling effect that stretches far beyond Panjab ‘95. “People have stopped writing what they want,” Trehan says. “Everyone is self-censoring. And that’s the most dangerous form of censorship — when you start policing yourself.”

The Chilling Effect — How Fear Fuels Self-Censorship in Indian Cinema

As Honey Trehan’s legal struggle over Panjab ‘95 drags on with no official resolution, the ripple effects of his case are increasingly being felt across the Indian film industry. Directors, screenwriters, and producers now speak — often anonymously — about a growing tendency to avoid politically sensitive subjects altogether. The ghost of censorship now haunts the writing room, not just the edit bay.

“I’ve shelved two scripts this year alone,” a veteran screenwriter shared under condition of anonymity. “One involved a journalist investigating custodial deaths, and another was a satire on election campaigning. I didn’t even bother developing them further. What’s the point? They won’t get cleared.”

This climate of fear, also known as the ‘chilling effect,’ occurs when creators preemptively dilute or discard controversial content to avoid regulatory retaliation. And in the Indian context, it’s a rapidly normalizing practice.

Trehan believes that Panjab ‘95 is just one example among dozens. “Everyone in the industry saw what happened to us,” he says. “No one wants to go through that. The process isn’t just slow — it’s humiliating. It breaks your will.”

Film trade analysts report a significant dip in the number of socio-political dramas being pitched or financed since 2021. Historical biopics, which once enjoyed a renaissance, are now under close scrutiny for ‘nationalistic alignment.’ Any portrayal of institutional corruption, caste violence, or communal conflict is seen as a red flag.

“Studio executives now advise us to keep films apolitical,” said a young filmmaker from Mumbai. “They’ll say, ‘Let’s not take risks. Just make something entertaining.’ Even OTT platforms have become wary since the Tandav controversy.”

The OTT space, once celebrated as a haven for creative freedom, has also been brought under the CBFC’s regulatory purview through new IT Rules introduced in 2021. While not officially part of the certification process yet, these rules create a framework for content policing based on ‘public order,’ ‘morality,’ and ‘national integrity’ — all loosely defined and widely interpretable terms.

In this atmosphere, filmmakers are turning to euphemism, metaphor, and safe nostalgia as shields. “You’ll notice more films set in the 70s and 80s, but not dealing with actual history — just using it as an aesthetic backdrop,” says film critic Deepika Raman. “It’s a way of appearing meaningful without touching real issues.”

For many creators, this self-censorship begins before pen touches paper. It’s now a mental filter — what can we say, how can we say it, and most importantly, should we say it?

This trend is deeply concerning for Trehan, who fears it will erode Indian cinema’s power as a medium of truth-telling. “Cinema has always been a mirror to society,” he says. “If that mirror starts distorting the reflection to please the powerful, then what are we left with? Just glossy illusions.”

He emphasizes that Panjab ‘95 was never meant to be incendiary — only honest. “This is a film about one man who stood up and spoke truth to power. And they silenced him. Now they’re trying to silence the film about him too.”

Jaswant Singh Khalra — The Martyr India Forgot

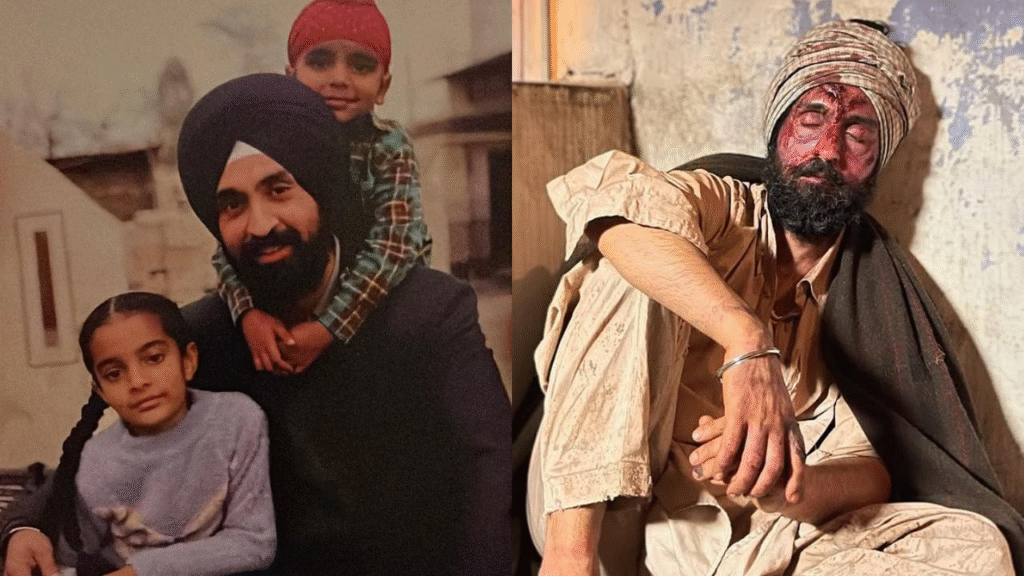

At the heart of Panjab ‘95 lies the extraordinary true story of Jaswant Singh Khalra — a name that, despite his global recognition in human rights circles, remains curiously absent from most mainstream Indian discourse. Khalra was not a revolutionary in the traditional sense. He wasn’t part of any militant outfit or political group. Instead, he was a quiet, principled man — a bank employee by profession — who uncovered one of the most horrific human rights violations in India’s post-Independence history.

In the early 1990s, Punjab was emerging from the long shadows of a violent insurgency and counterinsurgency period. Thousands had died, many more had vanished without a trace. It was during this time that Khalra, while searching for a missing friend, stumbled upon municipal records from Amritsar showing unclaimed bodies being cremated by police — bodies with names, identification numbers, and even family details.

Khalra began meticulously documenting these entries. What began as a few dozen cases quickly escalated to thousands. His research revealed over 2,000 illegal cremations in just one district. The implication was devastating: the Punjab Police had engaged in large-scale extrajudicial executions, disposing of the bodies in unmarked pyres without informing families or conducting investigations.

Khalra’s findings were eventually presented at international human rights forums, including in Canada and the UK. His work drew the attention of Amnesty International and the UN Human Rights Commission. For the Indian government and state authorities, it was a public relations disaster. For Khalra, it was a death sentence.

On September 6, 1995, Khalra was abducted from outside his home in Amritsar. Multiple eyewitnesses saw plainclothes policemen forcing him into a vehicle. For weeks, officials denied any involvement. But after sustained pressure, a CBI inquiry was launched. The investigation revealed that Khalra had been illegally detained, tortured, and ultimately murdered by officers of the Punjab Police. His body was never found.

In 2005, after a decade-long legal struggle, six police officers were convicted for their role in Khalra’s abduction and murder. The case remains one of the few instances where law enforcement officials were held accountable for atrocities during the Punjab counterinsurgency.

And yet, outside of activist and academic circles, Jaswant Singh Khalra remains largely unknown. No chapter in Indian school textbooks is dedicated to him. Few documentaries or public memorials exist. Honey Trehan’s Panjab ‘95 aimed to change that.

“This isn’t just a story — it’s a national reckoning,” Trehan says. “Khalra stood for truth, justice, and dignity. He paid the ultimate price. But the system he exposed continues to suppress his story, even today.”

For Trehan, the emotional responsibility of doing justice to Khalra’s life was immense. “I didn’t want to sensationalize anything. The script was built on facts, on court documents, on interviews with his family and colleagues. We weren’t making fiction — we were chronicling a legacy.”

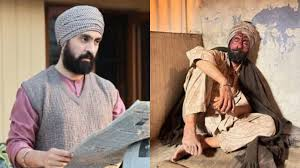

Diljit Dosanjh’s casting as Khalra was equally deliberate. Known for his rooted performances and credibility in Punjab, Dosanjh brought both authenticity and restraint to the role. “Diljit didn’t want to just act — he wanted to understand who Khalra was, what he stood for. He met the family. He read every document. He treated it like a responsibility,” Trehan says.

Despite this reverence and rigor, Panjab ‘95 has faced resistance at nearly every institutional level. “Why is it so hard to tell the story of a man who spoke the truth?” Trehan asks. “What are we afraid of? If we don’t remember Khalra, who will we remember?”

Also Read : Mumbai Police Increases Security Outside Kapil Sharma’s Oshiwara Home Amid Safety Concerns