Adoor Gopalakrishnan’s “Global Festival Gaze” Exposed as Caste Bias, Not Artistic Critique

At the Kerala Film Policy Conclave on August 3, veteran filmmaker Adoor Gopalakrishnan – long canonised as the moral centre of Malayalam cinema – voiced what was framed as concern but sounded unmistakably like caste-coded anxiety. Objecting to a government scheme offering Rs 1.5 crore grants to first-time filmmakers from Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe communities, and women filmmakers, Gopalakrishnan claimed that most recipients were not properly qualified and should undergo “at least three months of intensive training” before being allowed to make films. He proposed slashing the amount to Rs 50 lakh and dividing it among more people.

What passed as paternal advice was, in fact, a quiet rehearsal of caste hierarchy, dressed up in the language of artistic discipline. That his words invited immediate backlash was predictable. But it is their cultural undertone – the refusal to surrender inherited authority – that deserves closer attention.

Singer Pushpavathi, vice-chairperson of the Kerala Sangeetha Nataka Akademi and one of the few Dalit women in institutional positions of cultural visibility, called Gopalakrishnan out. His response, in an interview the following day, was to dismiss her as “a non-entity.” When reminded of her stature, he called her a “passer-by.” This was no slip. It was Manuvad in its most fluent form: the refusal to acknowledge a Dalit woman’s presence as legitimate, her critique as worthy.

Pushpavathi’s intervention was not simply about individual dignity. It revealed the grammar of who is seen and who is erased, who is heard and who is silenced. And that grammar, let us be clear, is caste. When critique from the margins is met not with rebuttal but with denial of existence, the wound is no longer aesthetic but ontological.

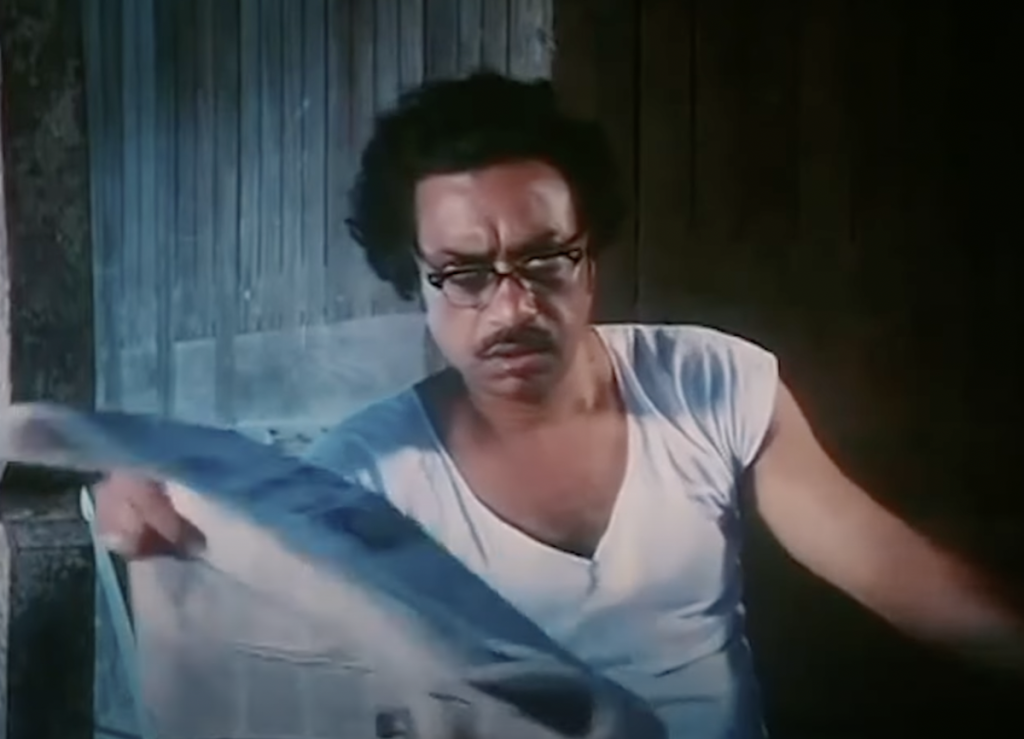

Gopalakrishnan’s condescension, in form and spirit, recalls his own film Elippathayam. In it, a decaying Nair patriarch watches the world pass him by. The land reforms, the political upheavals, the women around him – all push against his inertia. But he resists change not with fury, nor with insight, but with apathy. In one scene, a cow intrudes into his yard and begins nibbling on young coconut saplings (from around 15:30 onwards). From his poomukham (the semi-open, roofed verandah at the entrance of traditional Kerala homes), he makes a half-hearted gesture – more an assertion of entitlement than engagement.

Gopalakrishnan’s intervention at the conclave was that same gesture, replayed in real life: a feeble flick of the wrist against a world he no longer understands. The cow, this time, is the arrival of new filmmakers – Dalit, tribal, women – claiming the screen without waiting for permission.

Where Gopalakrishnan’s poomukham offers only aestheticised retreat, Malayalam writer Vaikom Muhammad Basheer offers another grammar in Njan Engine Oru Ezhuthukaranayi (How I Became a Writer)?. When a jackal strays into his yard, Basheer hurls at it the very Tamrapatram, the copper plate, awarded to him by the Kendra Sahitya Academy. It is an act of irreverence so radical it deflates the solemnity of state recognition itself. Basheer, the bricoleur, mocks the legitimacy that Gopalakrishnan, the engineer, seeks to preserve. One scavenges meaning from marginality; the other seals meaning within caste-coded refinement.

This is not merely a stylistic divide. It is a clash of worldviews. The bricoleur knows the system from below and mocks its symbols. The engineer builds it from above and demands reverence. The former disrupts; the latter preserves.

Gopalakrishnan belongs to the Tamrapatram generation and is a filmmaker whose frames are soaked in the light of official recognition, whose silences are not interrogative but consecrated. His cinema does not linger at the margins of society; it resides within its most protected interiors. It is no accident that Dalits, Adivasis, Muslims, and Christians – communities that have shaped Kerala’s modernity – barely appear in his films. And when they do, they are shadows: labourers, servants, unnamed threats. Never subjects. Never histories. Maybe symbols. Maybe metaphors. But never flesh, voice, or perspective.

One might point to Mathilukal, his film about Vaikom Muhammad Basheer. But even here, the exception proves the rule. Basheer is not an ordinary Muslim subject, he is a towering literary icon, already canonised by the state. His life, stripped of its political margins, is folded neatly into Gopalakrishnan’s aesthetic of solemn isolation. The Muslim enters not as a community, but as charisma.

Gopalakrishnan’s defenders will point to the formalism of his cinema – the long takes, the slow edits, and the meditative pace – as evidence of artistic intent. But formalism is never innocent. His glacial slowness is not just a rebellion against commercial tropes; it is the tempo of caste comfort, the stillness of a world that refuses to be unsettled.

The rhythm of Gopalakrishnan’s films does not subvert the social order, but aestheticises its endurance. The pauses in his films do not open space for contradiction; they reify the structures already in place. The silence is not contemplative, it is controlled. The stillness is not radical, it is regulatory.

Even in moments where his narratives appear to challenge order, they collapse into submission. Swayamvaram begins with a woman choosing her own husband in an act that gestures toward autonomy. But that choice is not sustained; it is punished. Her assertion of agency, rather than opening a grammar of freedom, is rendered as a fateful transgression.

One night, during her pregnancy, she dreams (from 1.12 onwards) of a temple pond full of lotuses. She steps into the water to pluck one. Suddenly, a hand pulls her under. It is her father’s. She tries to run, but her legs won’t move. She calls out to her husband; he is nowhere. She flees through a forest. The father chases. The imagery is vivid, mythic, but also unmistakably caste-coded. The daughter who dared to marry without sanction must now be retrieved by the symbolic force of caste patriarchy.

The Manusmriti still speaks through the dream: “Pita rakshati kaumare, bharta rakshati yauvane, putrah rakshati vārdhakye”—the father guards her in childhood, the husband in youth, and the son in old age. At no point is she her own. The moment of female autonomy must be narratively closed with ancestral dread.

In the final scenes, she feeds her infant from a bottle, rain falling outside. Her father is gone. Her husband is dead. A sex worker lives next door, and once, a few men – her customers – had knocked on the protagonist’s door by mistake. The protectors are missing; the caste gaze hovers anxiously. The camera lingers, not in solidarity, but in surveillance. She is stranded in the interregnum of patriarchy: between the guardian she fled and the guardian yet to come.

Gopalakrishnan’s cinema cannot imagine female agency unless it ends in drift or doom. It cannot accommodate ruptures unless they resolve into elegy.

And yet, international festivals lap it up. Why?

Because Gopalakrishnan offers the Global North precisely what it wants from the Global South: slow decay, metaphysical paralysis, upper-caste melancholy lit like Caravaggio and stripped of all political volatility. The Western gaze sees in his characters a soft, brown Hamlet, paralysed not by caste anxiety but by existential insight. His feudal inaction becomes Eastern profundity. His silence becomes philosophy.

This is the trick of the master’s gaze: caste-coded inertia gets exported as universal art. Political evasion is mistaken for spiritual aloofness. Gopalakrishnan’s protagonists don’t resist modernity, they sulk in its shadow. And the West, mistaking that sulking for wisdom, claps politely from afar.

Even Nietzsche’s tragic reading of Hamlet – the idea that the prince hesitates because he has seen through the horror of existence – finds an eerie echo in Gopalakrishnan’s frames. But what Nietzsche saw as metaphysical dread is, in this world, caste dread: the horror not of existence, but of its reordering. And like Hamlet, Gopalakrishnan’s protagonists hesitate not out of insight, but because the world no longer mirrors their place in it.

But even Nietzsche’s formulation must be held accountable. His ideal of tragic paralysis—elevated to metaphysical insight—has long been challenged by feminist, Dalit, Black, and decolonial thinkers who ask: whose horror is being universalised? Whose suffering is mistaken for profundity? In this masculinist, race-marked, Eurocentric schema, the hesitations of a privileged subject are projected as the template for all human insight, while the voices of those structurally excluded are treated as noise or absence. Gopalakrishnan’s films inherit this aesthetic solemnity and sanctify it. Across Nietzsche and Gopalakrishnan alike, what is structurally violent becomes ontologically tragic; what is caste-marked becomes aesthetically sublime.

This is why the silence in Gopalakrishnan’s cinema feels less like mourning and more like management. Less like loss and more like control.

Walter Benjamin, writing in the wake of fascist modernity, offered this vision of cinema’s emancipatory promise: “Our taverns and our metropolitan streets, our offices and furnished rooms, our railroad stations and our factories appeared to have us locked up hopelessly. Then came the film and burst this prison-world asunder with the dynamite of the split second…”

This is precisely what Gopalakrishnan’s cinema refuses. His camera does not detonate the rooms it enters – it preserves their aura, catalogues their despair, and leaves the debris outside the frame. The prison remains intact, made beautiful by its decay. The walls are not cracked; they are caressed. The violence is not shown; it is styled.

If one were to approach his films with historical curiosity – hoping to see what Dalits, Adivasis, or Muslims thought, felt, or endured during the transformations his narratives claim to depict – one would come away with little more than symbolic silence. Not the meditative silence of contemplation, but the sanctioned silence of erasure.

These bodies appear, if at all, only as figures in the periphery – labourers, threats, metaphors. They are not historical subjects; they are narrative props. Their exclusion is not an oversight; they are rendered unimaginable.

And so we must return to the question. Not whether Gopalakrishnan’s cinema is art, but as to whose absence it aestheticises, whose invisibility it preserves, and who gets to decide who matters.

When Gopalakrishnan dismisses a Dalit woman artist as a “non-entity” and a “passer-by,” it is not merely arrogance, it is caste speaking fluently. It is not a critique of artistic quality; it is a declaration of ontological worth. He was not just flicking away a dissenting voice – he was reaffirming who is allowed inside the poomukham, and who must wait outside the gate.

But the gate no longer matters.

The Indian constitution does not authorise any filmmaker – however decorated – to decide who belongs and who does not. It does not permit the guardians of aesthetic orthodoxy to distribute dignity by caste and gender. Cultural legitimacy is not a matter of lineage. It is a question of justice.

And justice does not arrive through the quietude of a well-lit frame. It arrives, as Benjamin foresaw, like the dynamite of the split second – shattering the prison-world, breaking the slow trance of reverence, and letting in the sound, colour, urgency, and assertion of those long denied the screen.

In short, Gopalakrishnan is not merely a chronicler of a crumbling order, he is its spectral father. Like the dream in Swayamvaram, he appears under the protective authority of tradition to drag Dalits, Adivasis, and women back into the depths, from where no voice escapes, and no gaze returns. This is the nightmare of the marginalised.

The question now is not only for us, but for those who continue to award, subtitle, and circulate this cinema as global art. Will the master’s gaze – the Global North’s festival gaze – ever develop a sense of justice? Or will it remain content with slow, beautiful erasures, so long as they are lit exquisitely and framed just right?

Also Read: India China Bonhomie Reshaping Trade and Challenging U.S. Influence in Asia