Bhupender Yadav’s Vision: Can Democracy and Development Coexist in India’s Environmental Future?

Bengaluru: On May 29, Union environment minister Bhupender Yadav spoke at the conclave of the Confederation of Indian Industry (CII), at a programme that was themed on “Building Trust – India First” and how climate, the environment and sustainability play a crucial role in this, with regard to industry.

Yadav called India a “land of development-oriented nature worshippers”, and said that India’s is a “story” of “democracy walking alongside development”, in the context of India’s economy rising ‘ahead’ of Japan, the United Kingdom and France. Prime Minister Narendra Modi has made environmental protection a “participative process”, he remarked, referring to Mission LIFE, a programme implemented by the current NDA government. India’s climate action and policy are built on building trust, and ensuring that India comes first, he said.

While Yadav dropped all the ‘right’ words and phrases in his speech – climate resilience, commitment to sustainability, and India being a voice of the Global South – there’s mounting evidence to show that India does not walk the talk when it comes to some of these aspects. This is especially true in matters pertaining to the environment, and the ministry that Yadav heads, the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change

Here are five instances where democracy and democratic dissent do not seem to apply to the environment in today’s India, especially with regard to developmental projects.

1. Ignoring dissent about the Nicobar projects and democratic safeguards falling through

A “disaster”, “death knell”, “catastrophic”: these are some of the adjectives that critics have used to define the slew of projects proposed by the Union government on Great Nicobar Island in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. The projects, costing more than Rs 72,000 crore, involve constructing an international transshipment terminal, a greenfield airport, a township and a power plant in the 970 sq km-small Great Nicobar Island that is surrounded by vibrant coral reefs and is the southernmost in the Nicobar group of islands in the Bay of Bengal.

The National Green Tribunal, India’s apex green court, has already ruled in favour of the projects despite the grave ecological concerns that social and science researchers have warned will affect both the indigenous communities living on the island (the Shompen and the Nicobarese, who are listed as Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups) and its endemic and unique biodiversity. The Union government has also already denotified a part of the tribal reserve which had been set aside for the indigenous communities; in 2021, the Union environment ministry under Yadav denotified the Galathea Bay Wildlife Sanctuary for the projects too.

The Andaman and Nicobar Administration, in a recent tender notification, claimed that gram sabha consent—which the Forest Conservation Act (1980) had mandated as essential for such projects—would not be required from the villages or the indigenous communities living in the area. This change is due to recent amendments to the Act, which exempt projects related to “national security” and similar categories from needing gram sabha approvals.

Conservationists and expert groups were quick to point out this loophole when the amendments were brought to Parliament for discussion in 2023. However, the government did not follow the proper process. The committee assigned to review the amendments overlooked key concerns and warnings raised by these groups, eventually pushing through the new Van (Sanrakshan Evam Samvardhan) Adhiniyam in 2023 without incorporating their recommendations.

Union Minister for Environment, Forest and Climate Change Bhupender Yadav speaks during the 24th edition of the World Sustainable Development Summit (WSDS 2025), in New Delhi, Wednesday, March 5, 2025. Photo: PTI

2. Anger brews in Arunachal courtesy the Siang mega dam, but the government is turning a blind eye

Protests are gathering steam in Arunachal Pradesh’s Siang district and its adjoining areas against the Siang Upper Multipurpose Project. This ~11,000 megawatt hydropower dam that India plans to build on the Siang river in northeastern Arunachal, just as it enters India from China, is touted as a response to China building its own mega dam upstream on the Siang. However, experts as well as local residents have repeatedly noted that the concern that water flow will decrease in the Siang after China’s dam is constructed does not rise because the Siang is also fed by streams on Indian territory.

Local communities have reiterated, time and again, that they do not want the dam as it will submerge their homes and agricultural lands, erasing their cultural identities. However, their demand has fallen on deaf ears: the state government has repeatedly deployed armed forces in the area, most recently over the past week to forcibly conduct a pre-feasibility study for the project.

Villagers took to the streets in hundreds, even burning a hanging bridge at Beging in Siang district last week in an effort to prevent the army from reaching the area. And yet the Union government turns a blind eye: armed forces still occupy these areas, and the state has filed complaints against an activist and lawyer, Ebo Mili, for allegedly spearheading these protests.

3. Cutting trees, displacing people, diverting land: There’s nothing that fosters sustainability or climate resilience here

In his speech at the CII on May 29, Yadav talked of climate resilience. The UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change defines climate resilience as the “capacity of social, economic and ecosystems to cope with a hazardous event or trend or disturbance”. Resilience includes adaptation abilities of people or communities to deal with climate change-related events such as floods and droughts. Yadav, in his speech, said that India’s climate policy is about green energy access to its people, and keeping our skies blue and our oceans clean; and that India remains the most trusted partner for the global world, for, among others, its “unwavering commitment for a sustainable world”.

One baseline to foster both climate resilience and sustainability is to protect existing natural ecosystems and wild spaces, as Yadav pointed out. India’s role as voice as the global South is supported by three interlinked drivers, he said, one of them being “protecting natural ecosystems and strengthening resilience”.

However, evidence from Chhattisgarh shows how the government is robbing people and local communities here of their existing sustainable ways of life and their ability to be climate resilient by permitting corporations to fell trees and mine coal in the very forests that people here depend on. In Chhattisgarh’s Hasdeo Arand, one of the last-remaining largest contiguous forests in the country, indigenous communities are still protesting the allocation of their forests as a coal block for mining by the Union government.

Activists and citizen groups have alleged that at least 15,000 trees were illegally felled in the Korba and Sarjuga districts here to carry out coal mining in the Parsa East Kete Basan coal blocks by a subsidiary of the Adani Group for its client, the Rajasthan Rajya Vidyut Utpadan Nigam (RRVUN, the power generation company of Rajasthan state). Villagers claimed they never gave their consent for mining but trees were felled in Parsa anyway. Violent clashes between residents and police followed. Later, an investigation by the Chhattisgarh State Scheduled Tribes Commission found that clearances for mining in Parsa block were given based on forged gram sabha consent documents.

Through petitions filed by activists, the matter is being heard at both the Chhattisgarh high court and the Supreme Court. This is one reason it cannot take up the petitions linked to the issue at the National Green Tribunal, the Tribunal said in an order on May 28 this year. In the judgment, accessed by The Wire, the Tribunal also added that it had already heard related cases and asked a joint committee to submit a “factual and action taken” report. On perusal of the report, the Tribunal said that the committee had not reported any violation.

In a previous judgment, the Tribunal had noted that authorities had taken “due permissions” for the cutting of the trees and thus disposed of the cases related to the tree felling submitted to the Tribunal. With the apex green court washing its hands off the issue, reprieve for local communities will now hinge on what the Chhattisgarh high court and Supreme Court rule on these cases.

4. Rights of forest dwellers remain on paper, many fear eviction from their homes

In 2006, India introduced the Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, also called the Forest Rights Act. It aimed to recognise and protect the pre-existing rights of indigenous communities who depend on wild spaces for sustenance and livelihoods, acknowledging that they also play a crucial role in conservation. Though hailed as a landmark legislation, this Act still remains mostly on paper nearly two decades later. Authorities of several states have not granted rights to many applicants: their claims have been rejected, making them vulnerable to relocation out of protected areas and their homes without their consent.

According to a 2013 estimate, six lakh forest dwellers have already been displaced from their forest homes. In June last year, the National Tiger Conservation Authority – which implements and oversees Project Tiger across the country, and operates under Yadav’s Union environment ministry – sent an order to wildlife wardens in all tiger states asking them to expedite the relocation of 591 villages, comprising 64,801 families, from all tiger reserves. Thousands of tribes from tiger reserves across the country have been protesting against this impending forced eviction since then.

According to one report, the government has identified at least 5.5 lakh Scheduled Tribes and other forest dwellers who live in 50 tiger reserves across India for involuntary relocation by Project Tiger to create “inviolate areas” for tigers. Petitioners had also filed cases in the Supreme Court regarding why the families whose claims had been rejected under the FRA had not been ousted from parks yet. Though the Supreme Court was to hear the crucial case pertaining to this in April, this has not happened so far.

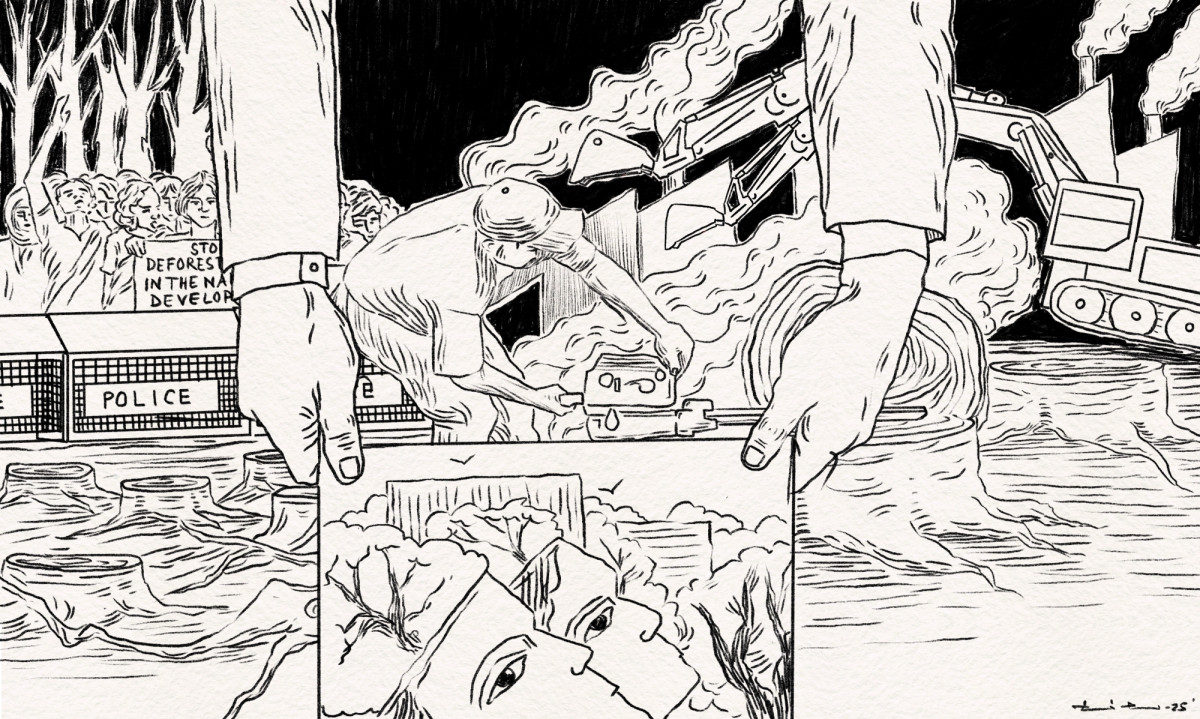

Illustration: Pariplab Chakraborty

5. Ladakh’s protests for the Sixth Schedule to protect their environment

In February last year, the people of Ladakh intensified their long-standing demand for statehood and inclusion in the Sixth Schedule through district shutdowns, peaceful protests, indefinite fasts, and long marches. Inclusion in the Sixth Schedule would grant Ladakh—designated a union territory in 2019 after being separated from the state of Jammu and Kashmir—tribal status, thereby providing local communities greater autonomy and a framework to protect their distinct cultural heritage.

This movement gained strong support from two key political groups, the Leh Apex Body and the Kargil Democratic Alliance. Additionally, renowned climate activist and innovator Sonam Wangchuk, a native of Ladakh, led several protests and “climate fasts,” urging the Union government to honor its promise of statehood and greater protections for the region. The BJP had included this promise in its 2019 election manifesto.

Among the prime reasons for these demands has been the fragile environment of Ladakh. With local communities already witnessing the impacts of climate change in the area, there has been stiff resistance against Union government-backed projects such as a 10-gigawatt solar energy project in Pang in the Changthang which would take up at least 150 square kilometres of prime grazing areas, and a geo-thermal energy plant (which is currently stalled due to technical issues). With Ladakh being rich in critical mineral resources, it could also witness mining for minerals such as uranium and lithium.

In April 2024, Wangchuk and Ladakh’s local leaders called for a “Pashmina March” to highlight how indigenous pastoralists are losing large tracts of prime pasture land in the Changthang – a high-altitude meadow where local communities graze their indigenous sheep, the wool of which is used to make prized pashmina shawls – to corporates who want to develop projects including energy projects.

In response to protests, the Union government came down hard on the people; it imposed curfews in Leh and other areas on multiple occasions. In October last year, dozens of climate activists from Ladakh, led by Sonam Wangchuk, marched from Leh to New Delhi’s Rajghat to remind the Union government of its promises to implement the Sixth Schedule in the Union Territory. However, they were detained as soon as they crossed the Singhu border and entered Delhi.

Many of the protesters questioned the state of democracy in India, shocked by the forceful response to a peaceful march. As news of the detentions spread, citizens from across the country expressed solidarity with the Ladakhi activists, calling on the government to listen. Eventually, the detainees were released, and the Union government agreed to hold talks with Ladakh’s leaders to work toward a resolution.

Talks are still ongoing at a snail’s pace, as Ladakh’s local leaders and the Union government rally on several points of discussion. Meanwhile, work linked to setting up energy parks and transmission lines in Ladakh continues. On May 28, the Power Grid Corporation of India (POWERGRID) – a government of India enterprise and the country’s largest electric power transmission utility – invited bids to establish a pilot project at the Pang HVDC (High Voltage Direct Current) station in Ladakh. The project involves constructing a 2,100 kilowatt off-grid solar photovoltaic power plant along with a 300 KW/1,200 kWh Battery Energy Storage System, with a provision for grid integration in the future, at a cost of about Rs. 137 million.

On May 22, it had also invited bids to set up a transmission line from Pang to Sarchu (on the border of Ladakh and Himachal Pradesh), associated with the transmission system for the evacuation of renewable power from energy parks in Leh (listed under the 5 GW Leh-Kaithal transmission corridor).

Also Read: Vande Bharat Express to Connect Kashmir for the First Time – Historic Rail Launch 2025 Begins