Devastation in Afghanistan: The Night an Entire Village Was Destroyed by Falling Stones

Kunar province, Afghanistan – It was a Sunday evening in late August when Hayat Khan returned to his home in the tiny village of Aurak Dandila. The 55-year-old farmer had been celebrating a wedding at a neighbour’s house – one of just nine stone homes built into the mountainside.

Partially concealed behind corn stalks and tall grass deep in the mountains of Afghanistan’s Kunar province, Aurak Dandila overlooks a patchwork of small farms, where the villagers grow corn and beans, walnuts and apricots. A stream cuts through the fields, and children would jump from the giant boulders that line it into the frigid, crystal-clear water.

Everyone in the village belonged to one extended family and thought of their quiet, peaceful spot overlooking the valley as a “little piece of heaven”.

The only way out was via a treacherous, unpaved road that snaked around a mountain – but most villagers survived off the land and had no need to leave. Those who did went in search of work in Afghanistan’s cities or neighbouring Pakistan and sent money home to those who stayed behind.

That morning, one of Hayat’s sons, 27-year-old Abdul Haq, had contemplated leaving.

Hayat knew what it was like to be away from the village. Six years earlier, when fighting broke out between the Taliban and ISIL (ISIS) fighters, Hayat had fled with his wife and children. In Lahore, the softly spoken father found work selling street food. But when he heard that the Pakistani authorities were cracking down on undocumented migrants and refugees, he decided to return. That was three years ago, and now he was back, happy with his life in the village, surrounded by his six sons and four daughters.

“Abdul Haq wanted to leave the village to get a paid job and make some money,” Hayat recalled. “But I told him to just keep being a farmer and God will give him food and all he needed.”

That night, when Hayat returned to the seven-room home he shared with Abdul Haq and 15 other members of his family, he went straight to his room to sleep.

At around the same time that Hayat was climbing into his bed, another villager was sitting outside her house.

Gulalai was talking on the phone to her husband, Khan Zada, who worked as a watchman in Pakistan. Earlier that night, he’d shared the good news – in 10 days, he’d be returning home for a visit.

Gulalai had told their six children, who’d gone to bed happy after a dinner of beans and pumpkin. Now, the couple in their late 20s were excitedly making plans for the visit.

Gulalai’s house was on the other side of the stream from Hayat’s and sat perched against the mountain, its large grey boulders high above. The three-storey house had been built by her father-in-law with the kind of love and attention that instilled pride in the family.

“He handpicked every piece of wood and stone from around the valley,” she explained.

“We used limestone to whitewash the inside of the house, and the colour of the window frames and door was red. If any of the kids damaged anything around the house, my mother-in-law would always remind them how hard their grandfather worked to build it.”

It was, she added, “as beautiful as a flower”.

It wasn’t long after Hayat closed his eyes that he woke to a feeling that “the earth was boiling”.

“It was like a black, dense storm of dust and stones.”

He screamed for his sons.

“I was looking for my phone to use its torch, but I couldn’t find it. I used the small light from my watch, and a cloud of dust hit my face.”

That was when he saw Abdul Haq lying dead in the rubble.

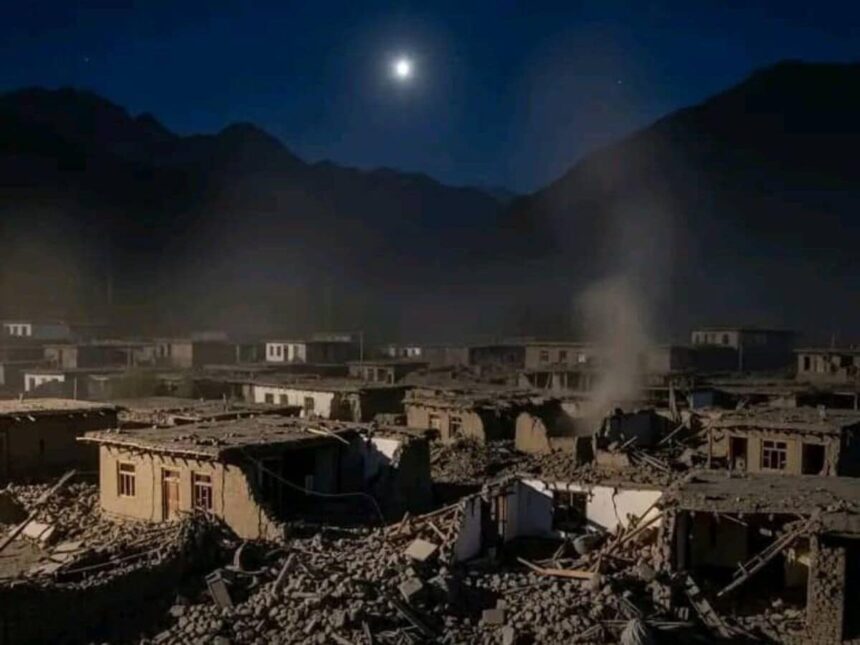

A magnitude 6 earthquake had struck Afghanistan, killing approximately 2,200 people and destroying more than 5,000 homes, most of them in Kunar, according to Afghan authorities.

As the earth shook, large boulders fell from the mountain onto Aurak Dandila, destroying everything. By the time the dust settled, all that remained was a single wall with a window and a badly damaged house on the outskirts of the village.

“I took my son out, and I kept coming to the house to try and save the others,” Hayat explained, remembering how, earlier in the year, he’d asked Abdul Haq to get married, but his son had initially rejected his request.

“He said he must improve his economic condition first. I told him our condition is good, and if we are all together as a family, life will always be good. He finally gave in and married two months ago.”

Hayat lost four members of his family that night: Abdul Haq and his wife, his oldest son Zai Ul Haq, 30, and Afsa, his two-year-old granddaughter.

Sitting on a stone under a walnut tree, Hayat began to cry. He held his head in his hands as a heavy silence descended upon the valley, broken only by birdsong and the sound of water rushing downstream.

“I saved one of my grandsons, and I was hearing other calls while I was rushing back to the house: ‘Uncle, uncle, save me.’ I recognised my grandson Zubair’s voice, but I couldn’t find him,” Hayat said, wiping tears from his face.

“I found him early in the morning; he was stuck in the rubble under a window.”

Hayat managed to pull his grandson out, and a rescue team eventually evacuated him to an emergency hospital about 200km (125 miles) away in the capital, Kabul.

“They have amputated one of his legs. He is just six years old,” he said, adding, “You cannot forget these things that break your heart.”

Trapped under the rubble, Gulalai could see that her house was still standing. She called out for her 14-year-old son, Zafar Khan.

“Then the big boulders rolled from the mountain and destroyed our house.”

Gulalai lost 14 members of her family, including all six of her children – Zafar Khan, 10-year-old Haleema, eight-year-old Khadija, six-year-old Abbas, four-year-old Hajira and Zinab, who was just two.

“My brother-in-law lost his wife and all his five children — four boys and one girl. One sister-in-law, who wasn’t married yet, also died together with my father-in-law.”

Gulalai, her mother-in-law and her brother-in-law were the only ones to survive.

She described how, unable to feel the pain at first, she’d “tried hard to get out from under the rubble”. By the time her brother-in-law pulled her out and carried her to the farmland, she was screaming in agony. “There was nothing he could do to ease it,” she said of the pain.

At about 10 in the morning, after the earthquake, they spotted helicopters in the sky. Concerned that they might not see their tiny village below, the surviving villagers began waving their clothes in the air.

“They couldn’t land at the location where we were, [so the rescue team] had to carry us to where the helicopter could land,” Gulalai explained.

They cleaned the blood from her head and face, patched her wounds and then evacuated her.

When Khan Zada heard the news, he rushed home as quickly as he could. Back in the village, he pointed towards the mountainside. “That was where my house was. See that trail of stones? That was it,” he said of the house his father had painstakingly built when Khan Zada was a young boy.

Now, Gulalai said, she does not want to return to the village and hopes her husband can find them somewhere else to live. “The rest of our life remains buried under the rubble,” she said.

A few metres away from the piles of stones that were once the first homes as you entered their small village, three men sat on a traditional woven bed.

One of them was Hayat’s cousin, Mehboob.

“When the earthquake happened, my 13-year-old son Nasib Ullah was sleeping next to me. I woke up, got out of bed, and started looking for the torch. Then, suddenly, the whole room moved from the falling rocks. When I tried to reach my son, the wall and the floor slid down, and I couldn’t catch him,” the 36-year-old explained.

“[It was] worse than the day of judgement.”

“Houses collapsed, boulders from the mountain came crumbling down; you couldn’t see anything, we couldn’t see each other.”

Everyone was injured, he explained. Some had broken ribs and broken legs.

“In the dark, we took our kids who were still alive to the farmland below, where it was safer from the boulders.”

That night, he counted more than 250 tremors, he said: aftershocks that continue to shake the valley even weeks after the earthquake.

When daylight came, he tried to dig through the rubble to find his loved ones. “But my body didn’t want to work,” he said.

“I could see my son’s foot, but the rest of his body had disappeared under the rubble.”

His 10-year-old daughter, Aisha, had also been killed.

“It was the worst moment of my life,” he said.

It took two days for villagers and volunteers to recover the bodies.

When Hayat’s brother, Rahmat Gul, received a message from his brother telling him that the entire village was gone, he immediately rushed there from his home in Parwan province, some 300km (185 miles) away.

When he finally reached Aurak Dandila, the surviving villagers asked him to wrap Mehboob’s dead son in a blanket.

“Mehboob asked me to show him the face of his son, but I could not do it,” Rahmat Gul explained as Mehboob, sitting beside him, looked out over the farmland in the valley below.

Nearby, Hayat stood up and began pacing.

“God has taken my sons from me, and now I feel like I have left this world as well,” he said.

In Aurak Dandila, a small cornfield has become a graveyard. “Here is where we buried our loved ones,” Hayat said. The graves are marked by stones.

He remembers how he had urged Abdul Haq to stay in the village. “The next day, everything was gone, and he lost his life.”

Now, Hayat believes, “there is nothing left to live here for”.

“How can I continue living here?” he asked, pointing at the debris of what was once his home.

“The stones are coming from above; how can anyone live in this village?”

“We will settle somewhere else, and we will look for the mercy of God. If he has no mercy on us, then we will also die.”

Also Read: Ladakh Turmoil Explained: How J&K’s Bifurcation Triggered Unrest