EC Asks Rahul Gandhi to Submit ‘Vote Chori’ Declaration and Proof – Candidate to Provide Evidence Under Oath

In an unprecedented move that could define the narrative of Indian politics in the upcoming 2025 general elections, the Election Commission of India has formally asked Congress MP Rahul Gandhi to provide a signed declaration—under oath—substantiating his public allegation of “vote chori” (vote theft). The directive comes in the wake of Rahul Gandhi’s repeated claims on campaign platforms and social media alleging systematic electoral manipulation by the ruling party. The Election Commission, responding to what it describes as a “serious and damaging allegation against India’s democratic process,” has asked Gandhi to submit formal documentation and credible evidence supporting his assertions.

The episode has triggered a political firestorm. The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has accused Gandhi of attempting to undermine public trust in the electoral process, while Congress has stated that the move by the EC is “an attempt to silence dissent and curb free speech.” As the political temperature rises, the episode represents a defining moment in the evolving relationship between India’s democratic institutions, its opposition leaders, and the public narrative around electoral legitimacy.

The Historical Context: Rahul Gandhi’s Critique of Democratic Institutions

Rahul Gandhi has, over the last decade, emerged not just as a central figure of opposition politics but also as one of the most vocal critics of what he alleges is the “institutional capture” by the ruling establishment. His commentary—delivered both inside and outside Parliament—has often focused on what he calls the “systematic dismantling of democratic institutions.”

In particular, Gandhi has been sharply critical of the Election Commission’s functioning. During the 2019 and 2024 general elections, he raised questions about the impartiality of the poll body, accusing it of selectively targeting opposition parties and turning a blind eye to the electoral misconduct of ruling party candidates. His 2025 statement claiming that the “entire electoral system is compromised and manipulated” was perhaps the most direct accusation yet—and it marked the point at which the EC decided to formally intervene.

Vote Chori: An Explosive Claim

The term “vote chori”, literally translated as “vote theft,” carries significant weight in India’s democratic lexicon. It invokes memories of past political scandals—from booth capturing in the 1980s to EVM manipulation allegations in more recent years.

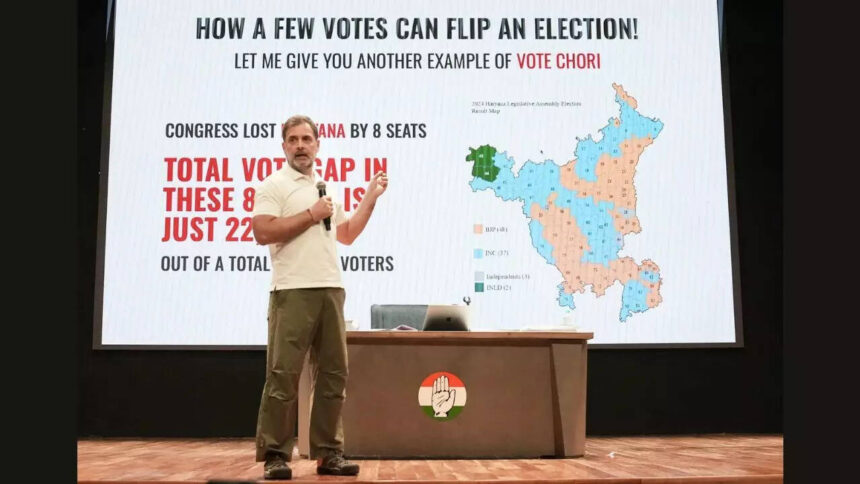

In a rally in Uttar Pradesh, Rahul Gandhi stated:

“Yeh vote chori ho raha hai, desh ke samvidhan ke khilaf sazish ho rahi hai. Janata ka faisla chhink liya ja raha hai.”

(“This is vote theft, a conspiracy against the Constitution of India. The people’s decision is being snatched away.”)

This statement, amplified through social media and mainstream coverage, sent shockwaves across the political spectrum. Civil society groups, legal analysts, and constitutional scholars began weighing in, some defending Gandhi’s right to question institutions, others warning of the dangers of delegitimizing electoral results without proof.

The EC’s Letter: Demanding Accountability or Silencing Dissent?

On August 5, 2025, the Election Commission formally issued a letter to Rahul Gandhi’s office. The letter, titled “Re: Demand for Declaration and Evidentiary Basis Regarding Public Statements on Electoral Malpractice,” includes the following directives:

- Submit a notarized affidavit detailing specific instances and evidence of vote theft as claimed.

- Provide the names of constituencies, polling stations, and any witnesses or documentation supporting these claims.

- Respond within 10 working days or face potential legal consequences under the Representation of the People Act and relevant sections of the IPC.

The EC emphasized that while freedom of speech is constitutionally protected, allegations that potentially “damage the credibility of India’s democratic systems” must be substantiated in good faith.

This letter marks the first instance in recent political memory where a sitting MP has been asked by the EC to provide a formal affidavit regarding a public political allegation.

Congress’s Counterattack: “A Threat to Democracy”

The Congress Party, in a press briefing led by senior leader Jairam Ramesh, condemned the EC’s action:

“This is not an impartial poll body demanding truth. This is a politically intimidated institution trying to muzzle one of the last voices of real opposition in India. Rahul Gandhi has every right to question the integrity of the process. Asking for a notarized affidavit is an intimidation tactic.”

According to the Congress camp, the EC’s letter is not a neutral act of constitutional discipline but a politically motivated attempt to shield the ruling party from scrutiny.

They also pointed to what they perceive as “double standards,” citing numerous instances where BJP leaders have made inflammatory or unsubstantiated claims with no institutional pushback.

Legal Analysts React: A Fine Line Between Accountability and Free Speech

Legal scholars are divided over the EC’s move.

Senior advocate Prashant Bhushan tweeted:

“Asking for a sworn affidavit is excessive. Politicians question institutions all the time. This could set a dangerous precedent.”

In contrast, constitutional expert Dr. Faizan Mustafa observed:

“Freedom of speech does not mean freedom to defame institutions without responsibility. If a politician makes serious allegations, they must be ready to defend them with evidence.”

The legal debate centers around whether political speech—especially in campaign settings—should be held to evidentiary standards or treated as rhetorical flourishes aimed at mass mobilization.

The BJP’s Stand: “Time to Expose the Lies”

For the BJP, this episode offers a political opportunity. The party’s IT cell and spokespersons have amplified the EC’s letter, calling it a moment of reckoning for Rahul Gandhi.

Union Minister Smriti Irani said:

“This is the same man who said ‘chowkidar chor hai’ and had to apologize in court. Now he claims vote chori. The nation deserves better than conspiracy theories and fake victimhood.”

The BJP’s communication machinery has been quick to turn the spotlight on what they describe as Gandhi’s “pattern of irresponsible and defamatory remarks,” demanding an apology if evidence is not produced.

Public Opinion: Polarized Reactions Across the Nation

On social media and in televised debates, reactions have been deeply divided.

- Supporters of Gandhi have lauded him for “speaking truth to power,” seeing the EC’s letter as part of a broader erosion of democratic freedoms.

- Critics accuse him of undermining democracy by making claims that can trigger public distrust in the election process.

A recent poll conducted by C-Voter suggests that 61% of urban voters believe politicians should be held accountable for public claims, while 42% believe Gandhi’s concerns are “legitimate and should be investigated.”

The Anatomy of the ‘Vote Chori’ Allegations and the EC’s Response

Following Rahul Gandhi’s explosive claim of possessing an “atom bomb” of evidence on “vote chori” (vote theft), the Election Commission (EC) has formally responded—triggering a constitutional and political standoff that has sent shockwaves through the electoral landscape of India.

Gandhi’s Evidence: What He’s Alleging

At a press conference on August 7, 2025, Rahul Gandhi intensified his attack by providing what he termed “proof” of vote theft, outlining five methods through which he claims electoral manipulation was carried out His allegations span across multiple states, including Maharashtra, where he questioned a suspicious rise in voter counts and alleged manipulation of polling processes

Critically, Gandhi accused the EC of withholding voter data in machine-readable formats and destroying CCTV footage—a move he interpreted as collusion in undermining electoral transparency

Formal Demand for Declaration and Proof

In response, the Karnataka Election Commission sought a formal declaration under oath from Rahul Gandhi, asking him to submit the names of allegedly ineligible or excluded electors to substantiate his claims and enable the initiation of necessary proceedings This move underscores the seriousness with which the poll body is treating these charges.

EC’s Broader Rebuttal

Earlier, the EC had dismissed Gandhi’s remarks as “baseless allegations” and directed electoral officials nationwide to ignore them while maintaining impartiality in their duties In parallel, Defence Minister Rajnath Singh publicly demanded that Gandhi present his so-called “atom bomb” evidence for public scrutiny

Public Mobilization and Demonstrations

Meanwhile, Congress ramped up its response with public mobilization. Leader Santosh Lad announced that Rahul Gandhi would spearhead a protest in Bengaluru, highlighting discrepancies such as “41 lakh extra votes in Mumbai and 61 lakh missing in Bihar”—amplifying the ‘vote chori’ narrative through mass engagement

Summary

- Rahul Gandhi presented detailed allegations and purported evidence of electoral malpractice.

- The EC countered by seeking formal documentation via a declaration from Gandhi.

- Senior ministers and the commission characterized the claims as unsubstantiated, prompting political escalation.

- Congress is mounting public protests, converting electoral integrity into a mass campaign issue.

Legal Foundations—Understanding the Framework Behind the ‘Vote Chori’ Dispute

The growing confrontation between Congress MP Rahul Gandhi and the Election Commission of India (ECI) has not only entered the political sphere but has also invited critical examination of India’s legal and constitutional framework governing elections. As the ECI demands proof and Gandhi asserts electoral fraud, the judiciary may be forced to arbitrate this confrontation rooted in two very different interpretations of electoral fairness.

The Representation of the People Act (1951): The Backbone of Electoral Law

India’s election process is primarily governed by the Representation of the People Act (RPA), 1951. This Act regulates the conduct of elections and provides mechanisms for the resolution of disputes:

- Section 8–10A deal with disqualification.

- Section 123 outlines what constitutes “corrupt practices.”

- Section 136 addresses the jurisdiction of courts regarding electoral matters.

Under Section 123, allegations such as manipulation of voter rolls, use of official machinery for electoral gain, booth capturing, or undue influence may constitute electoral malpractice. However, proving these claims requires hard evidence—affidavits, documents, data trail—rather than political assertions alone.

This is why the EC’s demand for a sworn declaration from Rahul Gandhi is not mere posturing—it’s a step toward potential legal proceedings if sufficient grounds are found to register a case under the RPA.

Indian Penal Code (IPC): False Claims and Perjury

Rahul Gandhi’s allegations, if proven false, could potentially fall under Section 182 (false information with intent to cause public servant to use lawful power to the injury of another), Section 211 (false charge of offence made with intent to injure), and Section 499–500 (defamation) of the Indian Penal Code.

Conversely, if the EC is found to have knowingly destroyed evidence or suppressed voter data, provisions under Sections 204 (destruction of documents), 217 (public servant disobeying law with intent to save a person), and 218 (public servant framing incorrect records) could apply.

This makes the current exchange not only politically explosive but legally precarious for both parties.

Constitutional Provisions and the Role of the EC

Article 324 of the Indian Constitution vests the superintendence, direction, and control of elections in the hands of the Election Commission. It is empowered to:

- Conduct free and fair elections.

- Issue binding instructions to electoral officials.

- Monitor electoral integrity across polling stations.

However, the EC’s role has increasingly come under public scrutiny. Accusations of bias, lack of transparency in the voter roll management, and delays in acting on complaints have dented public confidence.

Rahul Gandhi’s charge that the EC is no longer neutral is a direct challenge to its constitutional sanctity. If unaddressed, such a charge could erode public trust and force reforms.

Legal Remedies Available to Rahul Gandhi or the Congress

Should the EC reject Rahul Gandhi’s submissions as unsubstantial, Congress has recourse through legal channels:

- Filing an Election Petition in the High Court under Section 80 of the RPA if they believe elections in any constituency were materially affected.

- Seeking judicial review through a Public Interest Litigation (PIL) in the Supreme Court on the grounds that the EC violated Article 14 (right to equality) and Article 324.

- Approaching the Chief Election Commissioner (CEC) directly with voter roll anomalies backed by documents.

However, courts have traditionally been cautious about intervening in electoral processes unless strong prima facie evidence is presented.

Has This Happened Before? Precedents in Indian Electoral Jurisprudence

India’s election history is replete with legal disputes:

- In 1975, the Allahabad High Court found Indira Gandhi guilty of electoral malpractice, resulting in her disqualification and the infamous Emergency.

- In 2004, BJP’s Uma Bharti was disqualified for inciting communal tension during a campaign.

- More recently, EVM tampering allegations in 2017 and 2019 were dismissed by courts due to lack of empirical evidence.

Thus, if Rahul Gandhi’s claims are supported by legally verifiable proof, they could form the basis of a judicial inquiry of national importance. If not, they risk falling into the category of political rhetoric.

- The Representation of the People Act and IPC provide robust legal mechanisms for both prosecution and defense in electoral disputes.

- The EC’s demand for a sworn affidavit aligns with legal procedure under electoral law.

- Courts require verifiable proof, not just public allegations, to intervene in electoral matters.

- Precedents show that even powerful leaders can face disqualification—but only through due process, not political pressure.

As the confrontation intensifies between the Election Commission of India (ECI) and Congress MP Rahul Gandhi, public attention is increasingly fixated on the five-point accusation made by Gandhi that forms the spine of his “Vote Chori” (vote theft) narrative. In speeches across multiple states, and particularly in his response to the EC’s legal notice, Gandhi laid out a multi-layered claim of systemic manipulation—alleging that the ruling party, aided by a compromised administrative apparatus, rigged elections by exploiting loopholes in digital, physical, and administrative systems.

This section dissects each of the five claims Rahul Gandhi has referenced, tracing the technical, procedural, and evidentiary dimensions involved—and what each means for India’s democracy.

Manipulation of Voter Rolls: Names Missing, Lists Inflated

Gandhi’s first and most frequently cited allegation is that millions of genuine voters—particularly Dalits, minorities, and urban poor—were systematically removed from electoral rolls in BJP-ruled states. Congress claims to have obtained data showing:

- Massive deletions of names in urban constituencies without due public notice.

- Bogus names or duplicate entries inflated in BJP strongholds.

- Selective transfer of voters to distant polling booths.

Fact Check & Legal Lens:

Voter rolls are updated through a combination of Form 6 (inclusion), Form 7 (deletion), and Form 8 (correction), administered by local Booth Level Officers (BLOs). If deletion happens without proper field verification or notice, it’s a direct violation of EC’s Manual on Electoral Rolls and Article 14 of the Constitution.

However, substantiating this allegation requires certified voter roll data before and after revision, mapped against geographic and demographic trends—something Gandhi has not yet publicly disclosed in court-ready format.

Form 17C Manipulation – The Holy Grail of Polling Booth Data

Perhaps the most explosive technical allegation is that Form 17C—a statutory record of votes polled at every polling booth—was manipulated or misreported. According to Rahul Gandhi, in several constituencies, the total number of votes counted exceeded the number of votes polled, as recorded in these forms.

Understanding Form 17C:

Every polling officer issues this form on polling day, containing two parts:

- Part I: Records the total number of votes polled.

- Part II: Provided to candidates or their agents at the time of counting.

A mismatch between votes cast and votes counted is not only irregular but grounds for immediate legal challenge under Section 100 of the Representation of the People Act, 1951.

Congress’s Next Step:

If Rahul Gandhi’s team has photographic or scanned copies of Form 17C from polling agents, it could form strong admissible evidence in an election petition. However, no such documentation has been formally submitted to the EC or courts yet.

Alleged Use of Government Machinery for Voter Intimidation and Booth Management

Gandhi has alleged that state agencies—especially local police, state intelligence units, and district magistrates—were used to intimidate voters and manage booths in favor of the ruling party. These claims point to:

- Heavy police presence at opposition stronghold booths, discouraging turnout.

- Selective malfunction of EVMs in opposition-dominant booths.

- Unlawful transfers of polling officers in the run-up to election day.

Election Commission Protocol:

Transfers of electoral officers and deployment of security forces are monitored by the ECI, which also relies on randomization software for deployment of polling staff. Any manipulation here would require access to backend systems and collusion at a high administrative level.

Challenge:

The burden of proof again lies with the accuser. Unless detailed internal communications or field reports are made public, this remains politically persuasive but legally ambiguous.

Missing or Tampered CCTV Footage from Strong Rooms

Another technical pillar of Rahul Gandhi’s accusation is that CCTV footage from strong rooms—where EVMs are stored post-polling—was either missing, incomplete, or tampered with in key constituencies.

- According to Gandhi, Congress candidates in states like Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, and Gujarat filed formal complaints about disrupted surveillance feeds.

- There are claims that CCTV cameras mysteriously stopped working during critical hours before vote counting.

Electoral Norms:

CCTV surveillance of strong rooms is mandatory. Feed must be available to all contesting parties and monitored by Returning Officers. Any downtime or recording gaps must be logged with justification.

Legal Implication:

If logs are missing or footage was overwritten without explanation, it may indicate deliberate tampering—a violation under Sections 135A and 136 of the RPA, and a matter for judicial inquiry.

Allegations of Strategic Counting Delays and Server-Level Interference

In some of his more high-level claims, Rahul Gandhi has alleged that counting of votes was “delayed” in a manner that allowed backend manipulation—implying data-level interference with the ENCORE (Election Commission Network for Counting of Results) system.

Gandhi pointed to:

- Last-minute lead reversals in closely contested seats.

- “System not responding” errors reported by counting agents during crucial rounds.

- Possible server-based manipulation of digital result transmission.

ECI Rebuttal:

The EC has repeatedly asserted that ENCORE is air-gapped, meaning it is not connected to the internet, and that data transfer from EVMs to servers does not happen digitally, only manually via Form 17C entries.

Unless Gandhi’s team can prove inside access or illegal modifications to the system architecture, this allegation, while dramatic, may not hold in court.

Also Read : Adani Airports to Invest ₹20,000 Crore in City‑Side Infrastructure — 70% for Mumbai & Navi Mumbai