Fact-Check: Kolkata Floods — Was DVC, Farakka & Wetland Encroachment Really to Blame?

Kolkata: In the night between September 22 and 23, rains lashed Kolkata to an extent that has not been seen in the city since 1988. It rained 251.6 millimetres in 24 hours, Most roads in south Kolkata were inundated by waist-deep water. On social media, people shared images of books and possessions floating in their flooded ground-floor homes. Air, road and rail traffic came to a standstill.

It was a week until the Durga Puja festivities were to begin, so many roads and alleyways had already been blocked to put up pandals and decorations. Bamboo sticks, stored to be erected to accommodate the surfeit of festive advertisement hoardings, had clogged the lanes. Now the water made things worse.

By the end of September 23, it emerged that 12 people had died in Bengal, at least nine due to electrocution in the Kolkata area itself.

The Kolkata Municipal Corporation (KMC) tried to employ water pumps, but it took at least 48 hours for the whole of the city to lose its stagnant water. For many, during this time, there was no electricity as the power distribution company Calcutta Electric Supply Corporation decided to switch off power in some areas to prevent more deaths and injuries through electrocution.

In all, it was a terrible ordeal.

Early on September 23, the X account of Bengal’s chief minister Mamata Banerjee, in power in the state since 2011, and the leader of the Trinamool Congress which also controls the KMC posted a song for the festive season that Banerjee had composed. Over time, the Durga Puja has emerged as Bengal’s economic mainstay and Banerjee has been one to hype it up significantly.

She has incentivised puja organisers, set up a carnival in which Durga idols can be paraded in a procession before their immersion, and last year, in the aftermath of statewide protests over a junior doctor’s rape and murder, she had urged people to return to festivities. Even then, the tone-deafness of what was likely a scheduled post steeped in festive joy, irritated many. As criticism poured in, Banerjee gave quick interviews to top Bengali news channels. In those interviews and in a later post on X, the chief minister blamed a range of authorities for what Kolkata had to go through.

“This kind of rainfall has never happened before. Bihar’s waters entered the Ganga through Farakka, but dredging was never done. Neither DVC nor Maithon carries out dredging, and we are left to float in the water. Only tall talk, nothing else. My throat is sore listening to their empty words,” she said, according to PTI.

“Where will the water go when the Ganga is already full because no dredging has been done? When it rains like this in London, waterlogging lasts for 10 days. Even Delhi takes time to recover. But we don’t politicise deaths. These were unfortunate deaths,” she added.

On X, Banerjee wrote a similar thing in Bengali. The translation is mine: “The state was already flooded because of the unilateral release of water by the DVC, with rivers and canals overflowing. On top of that, large volumes of water are flowing in from Bihar and Uttar Pradesh through the Farakka Barrage, where lack of dredging has made matters worse. And now, this sudden, torrential rain has added to the crisis.”

Banerjee also blamed the CESC for the electrocution deaths and urged the company to add to the state government’s compensation for victims. The Sanjeev Goenka-owned company, thought to be rather close to Banerjee’s TMC, readily agreed, but added in a public post on X, “Kindly note that Street Light Poles and Traffic lights are not owned, maintained or managed by CESC.”

But while CESC may have had a role to play in the electrocution deaths, it is the claim that authorities controlling the Union government-owned DVC, Maithon and Farakka dams could be responsible for the Kolkata flooding that demands attention. In holding these responsible for the flooding, Banerjee is also, very adroitly, eliding over her own government’s very serious responsibility in taking away the one solution to the waterlogging problem in Kolkata, several experts say and show.

First, a few geographical positions. The DVC or the Damodar Valley Corporation is a statutory corporation which operates in the Damodar river of West Bengal and Jharkhand. Maithon, the dam Banerjee mentioned, is built on the Barakar river and has the largest of the reservoirs among dams maintained by the DVC.

Around 13 kilometres after the dam, the Barakar meets the Damodar, which is known to flood south Bengal often.

The Damodar meets the Hooghly at a place called Garchumuk, in the district of Howrah, to the south-west of Kolkata. The Datawrapper view of the Damodar meeting the Hooghly shows how its waters pour into the same river that passes through Kolkata, but after the city’s broadest limits are past.

“It is not that the lack of dredging is not an issue. The DVC’s decisions to release water often cause widespread flooding in the south Bengal districts, especially in low-lying Paschim and Purba Medinipur. But I don’t think the DVC was responsible for what happened in Kolkata,” says Debajit Datta, a professor who heads the geography department at Jadavpur University.

One of the many areas over which the state and Union governments are locked in a tussle is on how DVC chooses to release water, with Banerjee and her ministers often alleging it is not done with proper intimation. But Partha Pratim Biswas, a professor at the same university, who teaches construction engineering and has assisted several states in road, highway and aligned projects, agrees with Datta that the September 23 flooding in Kolkata could not have been caused by the DVC. “One does not need to be a scientist or engineer to know this.

It was localised and heavy rainfall – it was rainwater that flooded Kolkata, not the water released by the DVC. Kolkata isn’t affected by the waters let out by the DVC, it’s Howrah, Ghatal and the two Medinipur districts that suffer,” Biswas added.

What of Farakka, the other name mentioned by the Bengal chief minister?

The Farakka Barrage is across the Ganga river and near the Bangladesh-Bengal border. Its purpose is to divert 40,000 cusecs of water to the Hooghly – the part of the Ganga that flows through Bengal. Its stated purpose is to wash away the silt in the Hooghly. Its success in this regard is highly disputed. It has been blamed for more silt clogging up the Hooghly upstream and the river eroding away villages as it tries to find another path.

Then could the waters of the Hooghly have added to the rainwater and worsened the situation, like Banerjee is alleging? Not really, say the two experts.

Biswas mentions that siltation through the length of the Hooghly river is a huge problem and the riverbed is ripe for desiltation efforts, but both he and Datta maintain that lack of upstream dredging at Farakka cannot possibly have resulted in Kolkata flooding as a result of rain.

“Had this been the case, then the river Hooghly would have been responsible for floods in Kolkata – caused by the negligence at Farakkha – every time it rained heavily. Why would it be a one-time event?” said Datta.

Could Banerjee have meant that the silt in the Hooghly’s riverbed was preventing Kolkata’s rainwater from washing out? If she did, she would have been putting her hopes on an unscientific solution.

This is because Kolkata has a natural geographical slope from the west to the east. The Hooghly is to the city’s west. So the water from the city flows naturally from the west to the east – and not to the Hooghly. There are drains leading to the Hooghly from various parts of Kolkata, which can help in flushing the water out, through the river. But because the level of the Hooghly is higher than much of the city, there is no way water will flow out if not through pumping. Even then, during high tides, the lockgates will have to come down.

It is fortuitous that to the city’s east are river systems like the Matla and Bidyadhari and what was once the enormous East Kolkata Wetlands. These wetlands cover around 12,500 hectares of the state of Bengal, covering parts of Kolkata and two other districts. A Ramsar site since 2002, these criss-crossings of natural and man-made wetlands have functioned as the kidney of the city, ensuring Kolkata did not need an artificial system of treatment of sewage in the city. Left on its own, rainwater would flow naturally into the EKW.

It is here that the role of an authority that Mamata Banerjee did not mention comes into play – her own. Over the past few years, the EKW has shrunk at alarming rates. Construction on it has been encouraged by successive governments and now flourishes both legally and illegally.

There is also the Eastern Metropolitan Bypass, a 32-kilometre roadway to the east of the city that was made accessible to vehicles by 1982. “The bypass acts as a dam or a dyke, stopping the flow of water into the EKW,” says JU professor Datta. “Culverts were needed but they were not put there.”

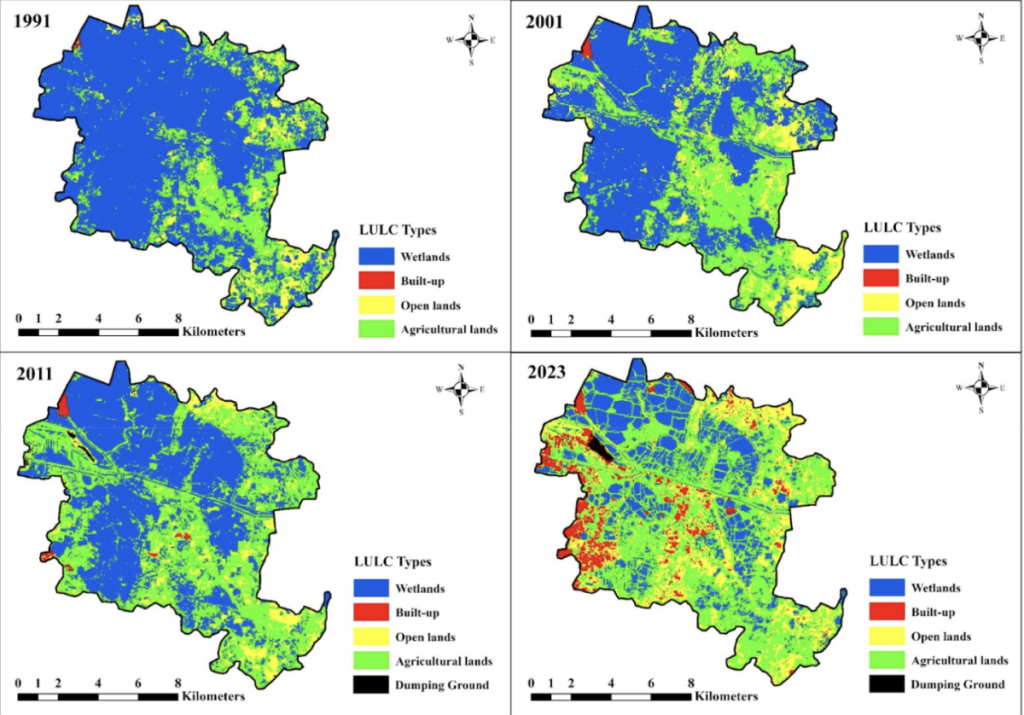

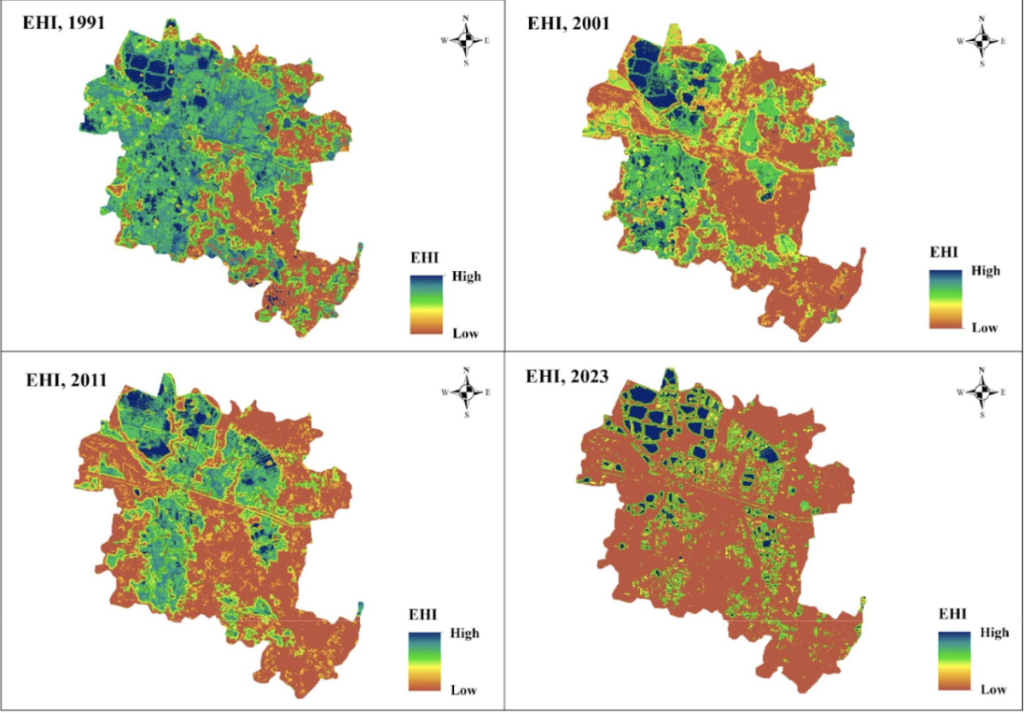

Priyanka Jha and her co-authors at New Delhi’s Jamia Millia University – Pawan Kumar Yadav, Priyanka Jha, Md Saharik Joy and Taruna Bansal, have published multiple studies on the EKW. In one paper published last year at the Journal of Environmental Management, they studied the evolution of the EKW over 32 years from 1991 to 2023. Their conclusion has been simple: Human activities are linked to the declining health of the wetland ecosystem.

In the above figure, Jha while speaking to The Wire, encourages readers to look closely at the dumping ground at the heart of the EKW, which has only grown in size between 2011 and 2023, as a symbol of the blatant disregard for the EKW’s health.

While degradation had well begun much before 2011, the year Banerjee came to power, it has been almost fast-tracked since then, the satellite images show.

For Bonani and Pradeep Kakkar, the testimony of the scientists is borne out by their own three-decade efforts to get the governments of Bengal to do nature’s bidding.

The Kakkars, through their NGO People United for Better Living in Kolkata (PUBLIC), in 1992, moved the public interest litigation in the Calcutta high court which resulted in the very first order granting legal protection to the EKW. Bonani, once part of the East Kolkata Wetlands Management Authority, told The Wire that she saw its democratic structure overtaken by a former mayor of Kolkata and then eventually, its gradual spiral into ineffectiveness.

Jha and her co-authors have written a new paper this year titled ‘Investigating the role of policies in the sustainable management of East Kolkata Wetland’ which notes that despite stringent regulations, weak enforcement mechanisms and inadequate monitoring systems are major barriers to effective wetland conservation.

The Kakkars have detailed records of how each mouza of the EKW has changed hands – often legally but in a way that defies explanation. “One of the areas with heavy encroachment in the EKW – Kheadaha II Gram Panchayat area, especially Bhagabanpur mouza, almost went under during these rains. The Kheadaha I Gram Panchayat area, on the other hand, is overwhelmed by plastic units that are unauthorised,” Pradeep Kakkar told The Wire.

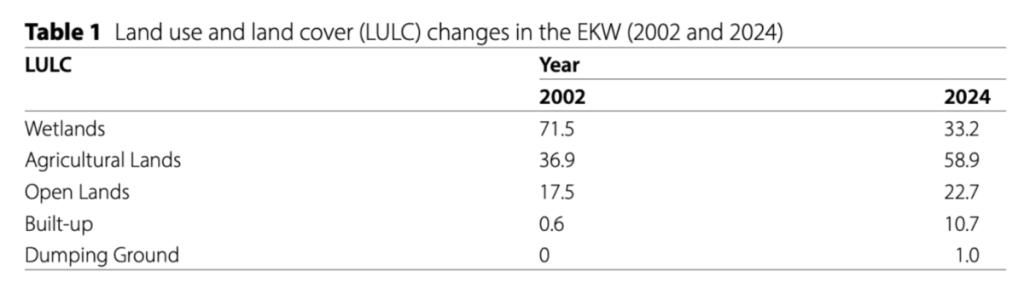

A table furnished by the Jamia researchers in their latest paper shows how land changed from 2002 to 2024.

In the above, the researchers highlight that the increase of open land indicates that land is being cleared for construction.

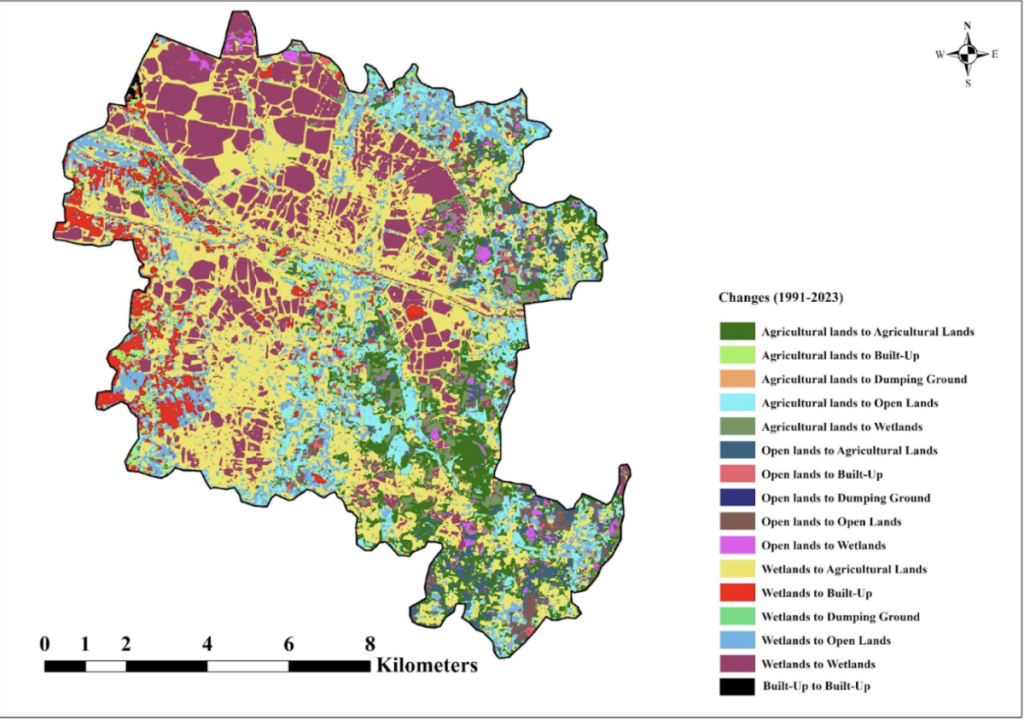

The following diagram illustrates much of the same.

These diagrams only drive home what is, in fact, plain to see – that construction on the EKW has increased several-folds in the last three decades.

Click on the play button below for a visual of the changes through the years.

In a low-lying city such as Kolkata, with climate change resulting in rising sea levels, there are obvious risks in sealing with concrete the very avenues that were naturally in place for the draining of water.

As chief minister, Banerjee has been quick to assign blame on factors which had little to do with this urban crisis, while ignoring a glaring and ongoing flaw in her own policies and those of her predecessors.

Incidentally, Banerjee once against blamed the waters released by the Centre-controlled DVC and Farakka for widespread flooding in the Himalayan and Himalaya-adjacent districts of Bengal – Darjeeling, Kalimpong, Jalpaiguri, Alipurduars and Cooch Behar on October 4 and 5. Thirty three people have died so far. However, both dams are, in fact, downstream from where the flooding and destruction happened.