Beyond the Mountains — The Return of Dialogue After Galwan

For the first time since the blood-soaked clash in the Galwan Valley disrupted a decades-old understanding between two of Asia’s largest powers, Prime Minister Narendra Modi will set foot in China. The occasion is the upcoming Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) Summit, scheduled for August 31 in Tianjin, and the significance of the moment cannot be overstated.

This is not just a diplomatic courtesy. It is a symbolic re-entry into a conversation that broke down the moment young Indian and Chinese soldiers, armed with nail-studded clubs and rage, clashed amid the freezing Himalayan air in June 2020. That night left 20 Indian soldiers dead — and an undisclosed number of Chinese casualties, casting a long and frozen shadow across bilateral ties.

Three years later, Modi’s planned visit to Chinese soil marks an unmistakable shift — one that’s equal parts strategic, cautious, and geopolitically urgent.

The Galwan Wound That Froze Dialogue

India and China have had a complicated, often uneasy relationship for decades, shadowed by the 1962 war and recurring border tensions. But since the late 1990s, both sides — pragmatic and growth-driven — worked around these disputes to build economic and regional cooperation.

That progress shattered in 2020.

The Galwan Valley clash was the deadliest encounter between Indian and Chinese troops in 45 years. The brutality was medieval, the terrain unforgiving, and the consequences long-lasting. For the first time in decades, Indian public opinion turned decisively against China — not just in New Delhi’s corridors of power, but in homes, markets, and social media timelines.

From trade bans on Chinese apps to stricter scrutiny of Chinese investments, the Indian government signaled that ties wouldn’t return to normal without a rollback of military aggression and forward deployment along the Line of Actual Control (LAC).

Diplomatic channels remained open, but trust had fractured.

What Changed Since Then?

Several rounds of corps commander-level talks, high-level phone calls, and even multilateral sideline meetings were held to defuse the military standoff. Some disengagement happened — notably at Pangong Tso and Gogra-Hot Springs — but large troop deployments remain in place on both sides of the LAC.

Despite this, realpolitik dictated that India could not permanently isolate China diplomatically — especially in forums like BRICS, SCO, and G20, where cooperation is critical to regional stability.

In recent months, two key developments likely influenced India’s decision to re-engage directly at a leadership level:

- China’s softening tone at SCO and BRICS platforms, particularly in addressing India’s security concerns without direct confrontation.

- India’s growing geopolitical leverage, including its leadership of the G20, expanding strategic relations with the West, and rising clout in the Global South.

In other words, India is now strong enough to talk, not compromise.

Why the SCO Summit in Tianjin Matters

The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) is more than just a regional forum. It is a geostrategic platform led by China and Russia, designed to foster economic, political, and security cooperation across Central and South Asia.

India joined as a full member in 2017. Though it’s not always aligned with the forum’s dominant powers, New Delhi has used the platform to:

- Counterbalance China’s influence in Central Asia.

- Build consensus on anti-terrorism and cross-border security.

- Forge energy and connectivity partnerships with Eurasian powers.

By attending the Tianjin summit, PM Modi sends three distinct messages:

- To China: India is open to dialogue — but from a position of strength and sovereign clarity.

- To the SCO bloc: India remains a committed player in the Eurasian space, regardless of its Western partnerships.

- To the world: India can engage even adversaries — diplomatically, maturely, and without losing face.

The Optics: First Modi Visit to China Post-Galwan

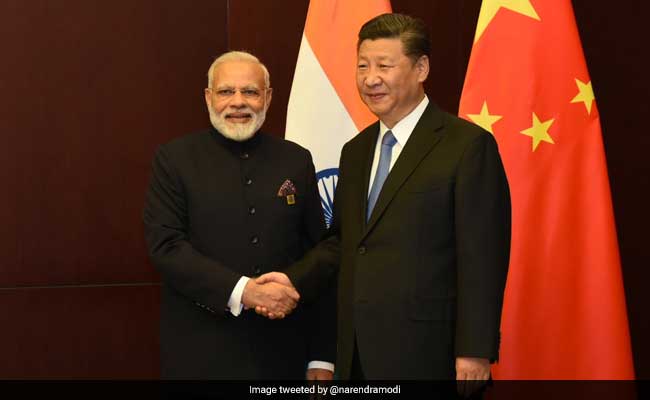

This trip is not just about what happens at the SCO roundtable — it’s about the optics, gestures, and protocols that surround it.

Will Xi Jinping personally meet Modi on the sidelines? Will there be a handshake? A joint statement? Or will they keep their distance and let diplomacy play out in subtler ways?

Either way, this is Modi’s first visit to China since Galwan, and that image — of a Prime Minister who once vowed retaliation, now stepping onto Chinese soil — will be parsed in every newsroom, embassy, and war room from Washington to Moscow.

But unlike 2020, this time India walks in with:

- A stronger military posture along the border.

- A growing global footprint, especially in tech, defense, and diplomacy.

- And a sharpened ability to balance East and West — playing both SCO and Quad without ideological contradiction.

India and China share more than just a border — they share centuries of civilizational weight, global ambition, and a deeply embedded rivalry wrapped in diplomacy. Over the past decade, this relationship has not followed a smooth curve; instead, it has zigzagged between cautious cooperation and confrontational mistrust.

As PM Modi prepares to visit China for the first time since the Galwan Valley clash of 2020, it is crucial to understand how this relationship evolved — not just at the diplomatic level, but in the minds of two nations with billion-plus populations, assertive governments, and competing visions for Asia.

The Xi-Modi Era: High Hopes, Then High Altitude Hostility

When Xi Jinping and Narendra Modi first met in 2014, there was optimism on both sides. India saw an economic opportunity in Chinese investments; China saw in Modi a business-friendly leader who could stabilize and accelerate India’s rise.

The early years were marked by warm personal diplomacy — remember the images of Xi and Modi sitting on a swing by the Sabarmati riverfront in Gujarat? That symbolism seemed to represent a new era: pragmatic, modern, and cooperative.

But the honeymoon was short-lived.

- In 2017, the Doklam standoff near the India-Bhutan-China tri-junction nearly led to a military escalation.

- In 2019, India revoked Article 370 and reorganized Jammu & Kashmir, which China — in support of Pakistan — strongly opposed.

- In 2020, the Galwan clash undid whatever was left of the fragile trust.

Since then, the relationship has entered what Indian diplomats call “a state of frozen hostility with open channels.”

Economic Ties: Competition Wrapped in Dependency

Despite the security breakdown, one area that remained oddly robust was trade.

India’s imports from China grew steadily, even in the years following Galwan. In 2023, China remained India’s largest trading partner, with trade exceeding $117 billion — largely in electronics, telecom, chemicals, and machinery.

However, the nature of this trade is asymmetrical:

- India imports heavily from China.

- India’s exports to China remain minimal.

This dependency has become a strategic vulnerability — one that successive Indian governments have tried to address by boosting domestic manufacturing (Make in India, PLI schemes) and diversifying import sources.

Yet, breaking free is easier said than done. Chinese firms are deeply embedded in India’s supply chains — from smartphones to solar panels. The Indian consumer market is a lucrative space for Chinese electronics and apps, despite government bans on over 200 Chinese apps including TikTok, WeChat, and others.

In essence, India and China compete politically and militarily, but cooperate economically — sometimes reluctantly.

Military Posturing: Mountain Chess and Maritime Moves

After Galwan, India changed its stance from deterrence by presence to deterrence by dominance in certain sectors.

- Forward deployment of Indian troops in Eastern Ladakh became the new norm.

- India increased its surveillance capacity with satellite coverage and drones.

- New roads and bridges have improved Indian troop mobility in frontier zones.

- The Rafale jets, purchased from France, were quickly deployed to forward airbases.

On the Chinese side, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) also ramped up infrastructure, rotated elite troops to the LAC, and used psychological operations — like new border villages and propaganda films — to assert territorial claims.

Yet the standoff has remained largely cold, not hot.

The real concern now lies in the dual-theatre doctrine: India must prepare for the possibility of a simultaneous threat from China and Pakistan. This strategic concern has led India to strengthen:

- Naval partnerships with the U.S., Japan, and Australia (through the Quad).

- Defense procurement diversification — from Russia, Israel, France, and the U.S.

- Joint military drills like Yudh Abhyas and Malabar exercises.

In a subtle but important shift, India no longer treats China as a competitor. It increasingly prepares for it as a potential adversary.

Public Opinion and Political Rhetoric: Nationalism Across Borders

Post-Galwan, Chinese products became a political flashpoint in India. Calls to “boycott China” echoed across WhatsApp groups, street protests, and television panels. Politicians across party lines found a common enemy in Beijing.

PM Modi himself, while careful not to escalate rhetorically, sent unmistakable signals:

- Surprise visits to forward areas.

- Military briefings at the LAC.

- Inauguration of high-altitude infrastructure projects.

In China, nationalist media portrayed India as both aggressive and weak. The Global Times, China’s state-aligned tabloid, repeatedly accused India of “provocations,” while lauding PLA restraint.

Yet both governments walked a fine line. Neither wants a full-scale war. But both are aware that domestic political capital can be mined from controlled confrontation.

Diplomacy in the Shadows: Silent Talks, Strategic Red Lines

Even during the most tense military standoffs, India and China kept talking — not just through official channels, but via Track-II diplomacy, academic exchanges, and multilateral sidelines.

What emerged over time were mutually understood red lines:

- India will not accept further Chinese encroachment or loss of status quo at the LAC.

- China will not accept India as an unquestioned regional hegemon, especially in South Asia.

Within this framework, co-existence remains possible, but never frictionless.

India’s participation in the Tianjin SCO Summit is not an act of reconciliation, but a calculated engagement within a limited framework.

As Prime Minister Narendra Modi prepares for his high-stakes visit to China for the SCO Summit in Tianjin, it is crucial to understand the stage on which this geopolitical drama is playing out: the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO). Behind the ceremonial handshakes and group photos lies a complex web of competing agendas, evolving power dynamics, and carefully negotiated positions.

The SCO is not just a regional forum — it’s a strategic theatre where China projects its influence, Russia defends its legacy, Central Asia seeks balance, and India asserts sovereignty.

What is the SCO?

The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation was established in 2001, originally as a mutual security alliance between China, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan. It was founded in the post-Soviet landscape to:

- Promote regional stability.

- Combat terrorism, separatism, and extremism.

- Develop economic and security cooperation.

Over time, it has evolved into a broader Eurasian political, economic, and security bloc. With the inclusion of India and Pakistan in 2017, the SCO became the world’s largest regional organization in terms of geographic scope and population, representing over 40% of the global population.

In recent years, Iran also joined as a full member, further tilting the group toward anti-Western alignments.

China’s Vision for the SCO: A Eurasian Power Platform

For Beijing, the SCO is not merely a diplomatic club — it is a strategic asset. Through it, China:

- Counters U.S. influence in Asia.

- Establishes connectivity via the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

- Exercises soft control over Central Asia through infrastructure, loans, and trade.

- Builds a regional security order that is non-Western, non-NATO, and authoritarian-friendly.

China uses SCO summits to push its vision of “multipolarity” — code for a world where no single power (i.e., the U.S.) dominates.

Importantly, while the SCO is often described as a security alliance, it has no collective defense mechanism, unlike NATO. It is a forum for consensus, not intervention — which suits China’s preference for non-interference rhetoric.

India’s Approach: Presence Without Alignment

India’s inclusion in the SCO in 2017 was a strategic gamble. On one hand, it gives New Delhi:

- A seat at the Eurasian table.

- Access to discussions with Russia, China, and Central Asia on terrorism and regional security.

- A chance to counter Pakistan’s narratives at a multilateral level.

On the other hand, the SCO includes Pakistan and China — both of whom India has hostile relationships with. India has consistently:

- Refused to endorse China’s BRI (particularly the CPEC project through PoK).

- Clashed diplomatically with Pakistan during SCO forums, especially over terrorism and Kashmir references.

- Treaded carefully on collective statements that seem to align with authoritarian regimes or anti-West rhetoric.

For India, the SCO is a platform for strategic signalling, not ideological alignment.

The Tianjin Summit: What’s at Stake?

The 2025 SCO Summit in Tianjin, China comes at a delicate moment:

- Post-Galwan tensions remain unresolved along the LAC.

- China-Pakistan closeness continues to deepen through military drills and economic cooperation.

- India-U.S. ties are at their strongest, with new defense pacts and technology agreements.

- The Ukraine war has redefined Russia’s posture, dragging the SCO into alignment with an anti-Western axis.

- Iran’s inclusion adds a sharper geopolitical edge to the group, particularly in the Middle East context.

In this setting, PM Modi’s visit to China is neither ceremonial nor casual. It is a high-wire act of diplomacy where every word, gesture, and absence will be scrutinized.

India is expected to raise:

- Cross-border terrorism (with an indirect reference to Pakistan).

- Respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity (a veiled pushback against both China and BRI).

- Connectivity on Indian terms (opposing BRI corridors through disputed regions).

- Energy and trade corridors (like INSTC, linking India with Central Asia and Russia).

SCO’s Real Purpose for India: Eurasian Access, Not Compliance

Despite its contradictions, the SCO remains India’s only formal grouping where it sits with both China and Russia — two powers that dominate Asian geopolitics.

Through the SCO, India:

- Engages with Central Asia beyond the Pakistani barrier.

- Ensures it is not excluded from Eurasian deliberations.

- Uses it as a stage to assert its own global standing — not through confrontation, but through diplomatic poise.

India does not see the SCO as a solution, but as a strategic opportunity — one that can be used without submission.

A Stage of Paradoxes

The Tianjin SCO Summit will likely end with a joint declaration full of generic affirmations on peace, cooperation, and economic development. But beneath the platitudes lie stark divergences:

- India and China disagree fundamentally on border, trade, and sovereignty.

- India and Pakistan clash on terrorism and regional strategy.

- China and Russia use SCO as a soft balance against the U.S., while India balances it without abandoning its Western ties.

Thus, the SCO Summit becomes a show of unity without true unity — a political theatre where strategic posturing takes center stage.

While official statements often focus on grand narratives of “regional cooperation” or “peaceful multilateralism,” what actually unfolds before a Prime Minister-level international visit is a high-stakes game of backdoor diplomacy, intelligence inputs, strategic hedging, and calibrated public messaging. This is especially true when the destination is China, and the backdrop is still shadowed by the 2020 Galwan Valley clash.

As Prime Minister Narendra Modi prepares to set foot on Chinese soil for the first time since the deadly Ladakh standoff, the groundwork for the visit has been months — if not years — in the making. While Tianjin and the SCO Summit are the visible setting, the actual game is played quietly in diplomatic corridors in Delhi, Beijing, Moscow, and Washington.

Intelligence Briefings: Reading the Terrain, Not Just the Map

Every move in foreign policy begins with an intelligence assessment. Before greenlighting Modi’s participation in the Tianjin SCO Summit, the Indian government relied on:

- RAW (Research and Analysis Wing) inputs on China’s military postures along the LAC.

- MEA backchannel communications with their Chinese counterparts.

- IB (Intelligence Bureau) reports on domestic reactions and risks.

- Inputs from defense attachés stationed in Beijing and Moscow.

- NSA-level consultations led by Ajit Doval.

The consensus was clear: while border tensions remain unresolved, China has also not escalated further militarily in recent months. That left the door open for a carefully choreographed visit — one that signals engagement without endorsement.

Moscow’s Role: The Quiet Stabilizer

Another key player behind the curtains has been Russia.

With Vladimir Putin’s close relationship with both Xi Jinping and Narendra Modi, the Kremlin has played a crucial intermediary role:

- Urging de-escalation post-Galwan through informal diplomatic messaging.

- Pushing both India and China to not let bilateral tensions derail multilateral cooperation in the SCO.

- Signalling to China that alienating India from Eurasian platforms could push New Delhi fully into the Western camp.

Russia, increasingly isolated due to its Ukraine war, needs both India and China to remain within its strategic orbit to keep the SCO relevant. It was likely Putin’s persuasion that convinced Beijing to allow a face-saving diplomatic format for Modi’s return to China.

Backchannel Diplomacy: MEA and MFA Engagement

Formal summits are only the tip of the iceberg. Below the surface, diplomats from India’s Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) and China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) have been:

- Negotiating language in the joint declaration.

- Agreeing on protocol sensitivities (Will Modi and Xi meet one-on-one? Will there be a handshake? What about photo-ops?).

- Working out red lines on public statements — especially regarding terrorism, Kashmir, and the Indo-Pacific.

India’s diplomats are acutely aware that China often uses multilateral statements to sneak in language favoring its geopolitical narrative. This time, they’ve insisted on tight editorial control.

Sources suggest that while a bilateral Modi–Xi meeting may not occur on the sidelines, there could be a “pull-aside” conversation — a diplomatic euphemism for informal chats with no official agenda but major symbolic value.

Domestic Optics: Managing the Nationalist Pulse

Back home, the Modi government walks a tightrope. Public memory of the Galwan clash, where 20 Indian soldiers were killed, remains emotionally raw. Any overt image of Modi appearing deferential on Chinese soil would:

- Be weaponized by the opposition (especially the Congress).

- Raise questions within India’s nationalist base.

- Appear contradictory to India’s Atmanirbhar Bharat narrative and border defense buildup.

Thus, every visual, every speech line, and every diplomatic phrase is being pre-tested for domestic optics.

The MEA has reportedly:

- Asked the Chinese side to avoid any symbolic locations linked to the People’s Liberation Army.

- Insisted on neutral flag placements and diplomatic parity during photo ops.

- Drafted talking points that reaffirm India’s stand on sovereignty and border integrity.

International Coordination: What the U.S. Knows and Watches

Even though the SCO is an Eurasian bloc often seen as anti-Western, India’s closest defense partner, the United States, has not been kept in the dark.

In fact, diplomatic sources suggest:

- India briefed the U.S. State Department and Pentagon about the visit and India’s strategic intent.

- Washington understands that India must keep a foot in both camps — the Western Indo-Pacific Quad and the Eurasian SCO — to maintain its global leverage.

- U.S. officials have even welcomed India’s participation in SCO summits as a balancing act against China’s dominance.

This confirms a new phase in Indian diplomacy — one where strategic autonomy is asserted by participation, not isolation.

The Role of Think Tanks and Strategic Communities

Beyond governments, strategic thinkers in India — from ORF to IDSA and CSDR — have been feeding in policy papers and briefings that help shape India’s messaging in SCO settings. These notes often stress:

- Non-alignment but proactive engagement.

- Reaffirmation of multilateral rules-based order (an indirect pushback against Chinese aggression).

- Linkages between SCO and India’s Central Asian energy diplomacy.

These institutions help the government create a cognitive narrative that aligns global policy with domestic confidence.

Opposition Watch: Political Traps to Avoid

India’s opposition parties are also watching closely. While foreign policy is traditionally kept above party lines, past instances — such as:

- Congress raising questions on Modi’s silence after Galwan,

- Or the TMC and AAP targeting Modi’s proximity to China in economic deals —

— reveal that even foreign summits are fair game in Indian electoral politics.

Thus, the Modi government’s communication strategy around the visit is being handled by:

- MEA’s public diplomacy division, and

- PMO’s digital media team, in coordination with the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting.

Everything from Modi’s airport departure visuals, to his meeting backdrop, to Twitter hashtags will be designed to:

- Show strength, not surrender.

- Display dialogue, not diplomacy for its own sake.

- Frame India’s participation as leadership, not concession.

Also Read : Trump’s Transshipment Crackdown Threatens Southeast Asian Economies and Supply Chains