Rajasthan Digital Governance: Companies Gain While Elders Lose Pensions

Bhilwara/Alwar (Rajasthan): In the dim light of Bedi Ka Badiya village in Bhilwara, Sangri Devi, who is visually impaired, sat quietly as her son, Dau Ram Gujjar, explained her struggle. Despite her old age and living below the poverty line, she finally secured a social security pension in 2014 after years of waiting. However, the ₹750 monthly payment was suddenly discontinued in 2022.

The family later discovered the reason: the government records had wrongly declared her “dead.” “This is the first time we have found out why her pension was stopped: Ki record mein yeh guzar gayin hain,” said Dau Ram. For two and a half years, no official explained the stoppage, nor did the family receive any formal notice or letter from authorities.

The family grazes sheep that had now huddled in the hut’s courtyard in the night. Devi, frail at 81 years, sat quietly in the darkness at the door of her hut, resting her elbow on her knee. Next to her, Balu Singh, a rights activist, sat on his haunches peering at the screen of his mobile phone. On an app’s green and white interface, he read out, “Current status: Cancelled” and “End/Stop reason: Death”.

On the ground, Singh had laid out Devi’s multiple ID cards, comparing them till he spotted a mismatch: her Aadhaar, a biometrics-linked ID card, stated she was born in January 1944, making her 81 years old, while her pension records noted her birth date in February 1953, implying she is 72 years old. The old age pensions scheme has two key criteria – that a family’s annual income is below Rs 48,000 and the woman is older than 55 years. A discrepancy such as this one did not disqualify her.

Balu Singh, secretary of the Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan (MKSS), a grassroots union in Rajasthan, shook his head. “In village after village, we see similar digital exclusion,” he said. “Earlier, the postman would bring a money order and give monthly pensions of Rs 500-750 in cash. We could see the amounts on the paper receipts, tally them, and even catch the postman if he asked for a bribe of Rs 10-20 to deliver it.” He added, “Now, after it became digital, the pensioner simply gets cut off. Even when they go physically, attempt to give online authentication, there is no log that someone has come.”

Rajasthan has over 90 lakh (nine million) pensioners. In 2023-2024, around 13 lakh (1.3 million) pensioners’ payments were “cancelled” citing their death or migration, but these included many who were wrongly declared “dead”, or shown as having left Rajasthan even when they were too old and too feeble to even step out of their homes. Officials in Jaipur said that of those declared “dead”, 95% of the decisions were done through automated processes.

Rizwan Ahmad, an activist with the Pension Parishad, a set of organisations advocating for universal pensions, said that thousands faced problems because of delays and “data mismatches” such as in gender, or discrepancies in names and spellings. Even when these errors were identified at the local panchayat level, officials told the victims to get it corrected in Jaipur, the state capital. Rajasthan is India’s largest state. A visit to the capital translates to being told to travel over 200 km to get data errors corrected for those who live in villages.

The digital technologies did not translate to greater transparency. Pension activists advocated for months, demanding that the government’s apps publicly display the reasons while cancelling hundreds of thousands of pensioners’ names across the state.

“Despite grave errors leaving so many individuals without support for months or even years, no one is held accountable,” said Ahmad. “Genuine pensioners put in considerable effort to navigate getting back on the registry, but are not compensated.”

Rajasthan is set to further digitise and switch to algorithmic systems to deliver essential public welfare. Digital records will be sorted through the help of complex computer algorithms, branded as “machine learning”, and these systems will determine who gets welfare and who doesn’t. “We will use existing data, metadata to build “360 degree profiles” on the poor as individuals, on their families and predict and verify their needs,” said Dheeraj Gaur, a systems analyst and additional director in department of IT in the state capital in Jaipur.

What Sangri Devi faced was only the latest in a series of ongoing digital experiments on the poorest’s pensions scheme.

‘I curse those who took my pension’

Under the National Social Assistance Programme, the Rajasthan government gives a monthly pension of Rs 1,150 to its most vulnerable residents living below the poverty line: the elderly, single women, and those living with major disabilities.

The elderly, especially widows, often battle deteriorating health and face neglect even in better-off families. Most of those belonging to historically marginalised castes in villages worked on farms, mines or in construction, and have few savings. Though the amounts are small, these pensions are a vital source of sustenance for them.

For Sangri Devi and her family, her small pension was their only steady source of income, and they struggled hard to get it reinstated. Her son Gujjar explained that they even paid ₹260 for annual online verification at an e-mitra, an e-governance kiosk. Despite his mother’s disability—she is blind and hard of hearing—he managed to take her with great difficulty to the local panchayat office.

However, the pension authority’s mobile app, which the family could not access due to the lack of a digital device, still showed “Not verified” in a small column. According to state records, Sangri Devi had failed to “mark herself alive,” a mandatory step in the pension registry to remain eligible for payments.

Some errors ended in tragedy. Between December last year and May 2025, two of nine pensioners who The Wire met and interviewed in central Rajasthan who faced difficulties completing biometric and digital verification processes – Dapu Devi and Amari Devi – passed away, cut off from their only means of income support in the final weeks of their lives. Hanja Bhil, another pensioner who has since died, was anxious when her daughter in law, a widow, lost her pension and neither of them knew how to rectify this.

In village after village, it was the most marginalised, those belonging to the Dalit castes, indigenous Bhil, pastoralist Gujjar families, elder single women who suffered from mislabelling and exclusion.

In central Rajasthan villages, where the MKSS union has its offices and worked with the pensioners to actively pursue these cases, they managed to get their benefits reinstated. But many pensioners were still waiting for compensation even after their names were reinstated.

Elsewhere, the elders have not been able to get their records corrected even after six months. For instance, in northern Rajasthan in Alwar’s Tulehra village, Parbho Devi Gujari was wrongly marked “Out of State”, or as no longer being a resident.

Gujari has dementia, is over 80 years old, and has been bedridden for the last three years. Her pension had stopped in January 2024. Her grandsons Jaisingh and Vijay Gujar said her biometrics no longer match her original enrolment data in Aadhaar, her fingerprints wouldn’t match. “I curse those who took my pension – may they fall in a well to perish!” muttered Gujari as she sat on her bed. After suffering a stroke, she is no longer coherent, they said. They found it difficult to physically take her pillion on the motorcycle to various offices to prove her presence.

Their situation became so desperate that last November, several pensioners tried to testify to the press in Delhi to show that they were alive. It was as part of a campaign to fight against being digitally excluded, organised by the MKSS and Pension Parishad.

Dipa Sinha, a development economist who advocates for better social security, said their testimonies showed how hard automation had made it for those not able to access digital technologies to merely prove that they were alive. “It is a disempowering system,” she said. “The government has become merely a computer interface. Village and block level officials say they cannot do anything because a software is not working, or a portal is not working that day. If a software is not working, then does it mean that no one is accountable?”

In the state capital, Jaipur, 250 km away, pension department officials said that between November 1, 2024 and April 30, 2025, more than 77,57,888 pensioners had verified their eligibility through various digital means and acknowledged that over 13 lakh pensioners remained. “When someone does not turn up for verification, we stop the pension. The pensioner can show up, verify and take it. It is not that we are dangling a sword over their heads,” said an official supervising this. He declined to be named, saying he is not authorised to speak to reporters.

After a large number of complaints and a few critical news reports, Hari Singh Meena, additional director in the Department of Social Justice, gave written assurances in a meeting with transparency activists at the end of 2024: The department would in the future give clearer reasons before cancelling pensions. In case of data mismatches, it would stop pensions but not “cancel” them without verification by field functionaries. Instead of 12 months, arrears may be provided for up to 36 months of lost pensions.

“We allowed village and block development officers the authority to “re-open” cancelled pensions. We said the local staff could verify the “deaths” in the gram sabha (village assembly). They could receive one-time passwords on their mobiles for those who cannot authenticate,” said B.K. Agarwal, a former director in the Department of Social Justice and Empowerment who oversaw the distribution of pensions last year.

‘Cradle to grave’

Rajasthan’s poorest are not new to this problem of death by their digital absence.

The Congress government followed by the Modi government pushed Aadhaar as a digital identifier on the national scale, arguing it would ensure welfare reaches those who really need it. Residents have to give facial scans, fingerprints and iris scans to get a 12-digit ID number. Biometrics fingerprint scanners often do not account for skin roughened by age or manual labour.

In 2015, the law specifying what citizens’ protections under Aadhaar would be was not yet passed. Still, the Rajasthan government pushed a switch of pensions payments from post offices to banks as part of Aadhaar-based payments. It simply struck off thousands who had not enrolled in Aadhaar or failed to open a bank account. Others were made ineligible if the e-mitra (e-governance services providers) made errors while linking the details of beneficiaries with their Aadhaar numbers.

Between 2015 and 2016, the state government declared a vast number – 2.9 lakh pensioners – dead. When district reporters of the Hindi daily Dainik Bhaskar surveyed families door-to-door in several villages in 28 of the state’s 33 districts, they found most who were declared dead then were still alive. But by June 2016, the state government claimed it had saved Rs 600 crore.

Since then, the volume of data and low-cost technologies available to the public sector has grown. So has the administrative pressure to show that digital technologies saved public funds by detecting fraud.

“On the tenth of every month, Bharat-Direct Benefits Transfer (DBT) mission (an office functioning directly under the Union cabinet secretariat) asks for the information, ‘How many ‘ghost’ and fake beneficiaries did you remove?’” said a senior official in the state government’s IT department in Jaipur. He added that there was similar pressure on every other office too, to show savings. “Sometimes we cannot find even a handful and have to show ‘Zero’, but most times we can show some data as the dead get removed in real time when their death certificate goes up online.”

India only mandated the registration of births and deaths in 1969, two decades after it gained independence from British rule. The Modi government amended this law in 2023 to introduce a national register, or electronic database of births and deaths, and said that households would be required to give details members’ Aadhaar to the registrar.

Now, by integrating pension schemes with the death registry, Rajasthan officials were trying to determine who had died and was thus no longer eligible. The IT department official said that to do this, they already used software and automated systems developed by RajComp Info Services Ltd, a government company, and Aurionpro, a Mumbai-based technology corporation, that credits government business for one-third of its tech innovation group work. In 2018, it had bagged the Rs 70 crore contract for “City Surveillance projects for seven Cities” in Rajasthan.

In 2022, it received a Rs 180-crore contract to build “the nation’s first 3-D model”, or a digital twin of Rajasthan’s capital, Jaipur for urban planning. Besides Rajasthan, the IT company had bagged surveillance contracts valued at over Rs 400 crore total from governments of Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra and Delhi in the last six years.

“Earlier we had no way of knowing if anyone on a welfare list had died,” said Sitaram Swaroop, an additional director in the Jan Aadhaar authority that comes under the state’s IT department. “Even if two or three members of a family died, the household would continue to receive five kg ration grains or small pensions some months. When we authenticate with Aadhaar, the database is authenticated and robust. As the death certificate goes up online, this gets communicated to the pensions portal in real time.”

He explained, “As various departments such as social justice, food, agriculture use our data to determine eligible beneficiaries, we too ‘reverse-seed’ their data. Such as, we can collate and interlink who gets pensions, who took farm loans, or even how many cattle does someone own, though it has been difficult to keep that last one up to date.”

Pension officials acknowledged that sometimes, there were errors such as when the wrong Aadhaar ID number got entered manually at the village. Other times, they explained, some got wrongly declared dead in a combination of manual and automated processes.

By the end of the pandemic, the state further tightened the digital gate-checks. In Rajasthan, the government reduced the exceptions provided to those whose Aadhaar authentication through biometrics verification or mobile passwords failed. After 2022, it made not only having the central ID, Aadhaar, but enrolling in a state database Jan Aadhaar (that uses data from Aadhaar, the Union government biometrics ID, as its foundation to create a family ID) compulsory, and synced the Aadhaar, Jan Aadhaar and pension portal’s data.

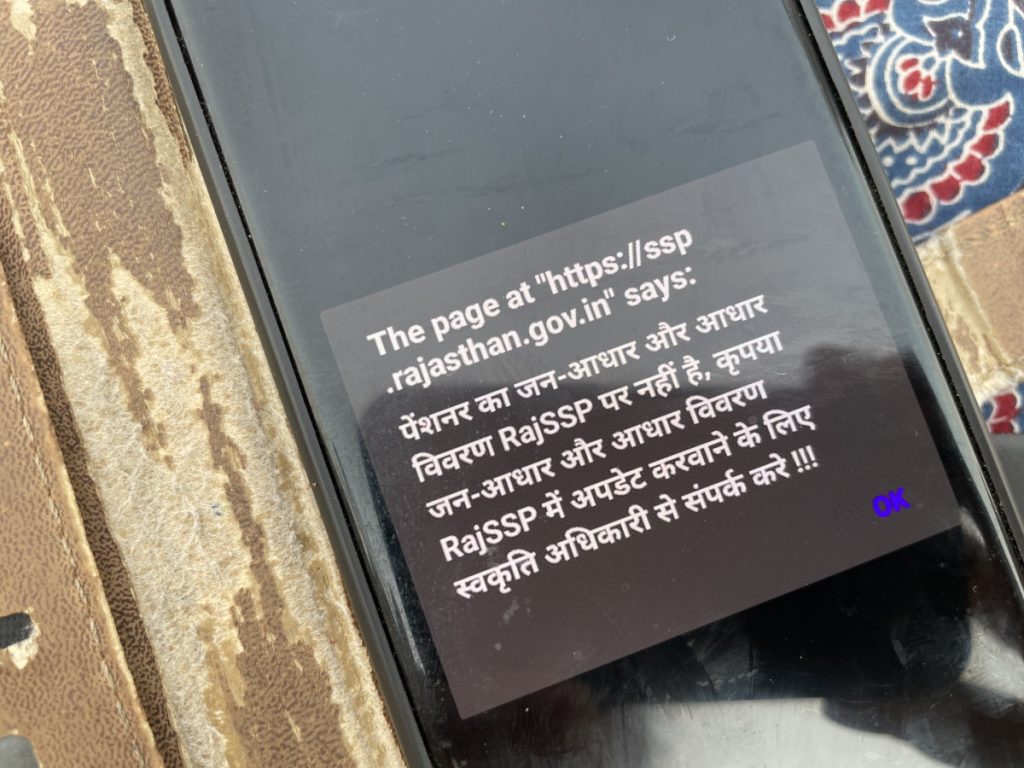

Those whose records presented even a small discrepancy, even if it did not change their pension eligibility, started encountering problems. Incomplete data left people stranded or led to their entitlements being disabled. They had little access to formal redress or grievance redressal locally.

In Ajmer district, Kanku Devi Bhil lives in a bare stone house on the edge of Kaanpura Chaurana village in Devaata panchayat. Bhil is a widow. Her son Maadhu died of cancer. She lives with her husband’s family, in which all male members have migrated for work. The men dig wells in Maharashtra, while her 12-year-old grandnephew works as a wage labourer in hotels in Gandhinagar in Gujarat, the neighbouring state.

The family is extremely poor, “Antodaya” or poorest of poor category as per the state ration records. Bhil, who is 68 as per her Aadhaar records, got a monthly pension of Rs 500 but it stopped in December 2022. When Bhil tries to authenticate using Aadhaar, her biometrics don’t work because her hand shakes. Those whose biometrics do not scan can receive a one-time password, but Bhim does not own a mobile phone.

Once a pension is stopped, it cannot be reopened without verifying the individual’s Jan Aadhaar data, say officials. Ranjit Singh, a local activist trying to help Bhil, said they ran into the problem that though her husband Kisna Ram is dead, he still shows up in her Jan Aadhaar or household ID records. Ram had died on January 7, 2018; the date is listed in the corner of a photo framed by his family at the time.

“At the time of his death, Bhil did not get his death certificate made. Now it is not easy to get it, years later. She has to request the tehsildar to make it, but his office is 25 km away. She cannot walk, she crawls, and the family has barely any cash left,” said Singh.

Showing just how pervasive the problems are, across the state highway from Bhil’s village, in Nayagaon in a neighbouring panchayat, Neni Devi Jangid remained cut off from pensions for two years. She was declared “Out of State” when she could not authenticate herself digitally, as she too suffers from tremors. She is over 70. She holds five ID documents that put her year of birth between 1944 and 1953. Her son Balu Singh Jangid, who drives an e-rickshaw, took her to e-mitra and block offices four times. As the family recounted their struggle, Jangid sat quietly trying to drink from a steel bowl, but her face and frail hands shook continuously.

Shankar Singh, a senior activist, grew up in central Rajasthan villages. He organised and took part in protests for a pioneering transparency law passed by the Rajasthan government in 2000 and co-founded MKSS. He said the switch to digital technologies was concentrating power in Jaipur and exacerbating inequalities.

“Bhil and other backward class families live in deep distress. You can tell it is so simply by looking at their bare homes, seeing their children who frequently have malnutrition.” Singh added that there was lack of timely and adequate redress. “For them, this pension is a life support. But in the switch to the “machine”, in the era of the “online”, nobody knows and nobody explains who has the power to alter and correct or fix these life-threatening errors and provide relief.”

Further centralisation

Agarwal, the former director in the Department of Social Justice and Empowerment who oversaw the distribution of the pensions, said digital authentication was necessary as earlier when the department would ask local officials at the block level to verify the pensioners’ status, they in turn would ask the field functionaries. But added that “grassroots workers often have their own political leanings and this makes the process dicey and complex”. He said that 95% of pensioners’ deaths had been found by the automated processes.

The IT department officials said besides using automation to remove those who may have died from welfare lists’, they had started to experiment with using algorithmic checks to detect fraud.

“After we synced Jan Aadhaar data with Aadhaar demographic data, we ran checks on the pension applicants to see if anyone had altered their date of birth in Jan Aadhaar and what updates had they made in Aadhaar,” said an official in the Jan Aadhaar authority. “Then, we looked for whether they had changed their date of birth just before applying for an old age pension.”

The fraud instances detected in over nine million pensioners were extremely low – just a handful. “We found 7-8 individuals who committed forgery, thus making themselves appear old enough for pensions in Karoli or Dausa districts.” He added that of the eight cases thus detected during verification, half the fraud claims had already been rejected by the pension officials through other checks. But this direction of policy was commended and encouraged by New Delhi.

“The news appeared one front pages,” he said. “Even the PMO and officials of the Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI, the central agency managing Aadhaar) got in touch and enquired how we had caught this fraud.” Earlier, a resident could change their demographics such as age in Jan Aadhaar, the family database, but now it had been centralised and only the Aadhaar birth date would be considered valid, he added.

Village and block officials said that the centralisation led to absurd situations. Kailash Chand, a rozgar sewak who implements rural development schemes locally in Dewata panchayat said he estimated that nearly 10% of those eligible encountered difficulties verifying online. But locally it was very difficult to provide any redress. “Once a pension was cancelled, we had little to no power, even if the person making a true claim stood before us,” said Pani Devi, sarpanch of Devata panchayat near Beawar.

The block development officer of Bhim, Rajsamand district, for example, sent multiple letters requesting Jaipur officials to reinstate pensions documents over minor discrepancies. One letter says, “Gangadevi” of Baar panchayat’s name has been changed to “Ganga Singh”. Her gender has wrongly changed from female to male and this is creating a mismatch which they cannot rectify. Another instance states that in Bhim panchayat, elderly Chhog Singh cannot access pensions as his date of birth in pension records makes him 99 years old, but as per Jan Aadhaar he is 88 years old. The qualifying age for old age Below Poverty Line pensions is 58.

Feeling helpless or uncertain, rural staff communicated problems like these to Jaipur through every medium: emails, WhatsApp, telephone, physical letters. It led to such a flood of complaints that the RajCOMP Info Services Limited (RISL) devised a solution: it created another website, a “Request Logger” portal, with instructions to communicate using only this.

“We started receiving 400 to 500 complaints daily,” said a staff of the company Aurionpro in Jaipur. “Now, it has reduced to around 100 complaints daily.” A circular of the IT department lists the categories of problems as mainly Aadhaar or Jan Aadhaar related, such as after eKYC(electronic Know Your Customer verification processes such as in banks), name spellings, gender or age show errors, errors in original demographic data in Aadhaar have got replicated into pension records, or the same mobile number has been linked to in multiple Jan Aadhaar ID records.

Decisions by machines

Despite the widespread disruption experienced by the most vulnerable, the state policy is gearing towards relying more on automation, with reduced human intervention.

Rajasthan is set to incorporate Artificial Intelligence (AI), a set of technologies that mimic human intelligence, specifically Machine Learning (ML) algorithms, to complete auto identification and removal of welfare recipients from lists such as the pension registry. Beneficiaries’ data will be used to create a Rajasthan Data Exchange, where aggregate, anonymised datasets from public schemes will be made available to companies and researchers at a price, say officials. In the 2024-25 budget, deputy chief minister Diya Kumari had announced a Rs 150 crore budget to build this.

“For private players, this data is a goldmine,” said an official overseeing the bid process. “Companies such as start-up enterprises want to know how to pitch their product line in a region, how to build a business model. We want to monetise ‘Big Data’ and let private companies pay for it. It will be like how you make purchases off Amazon in a cart then you pay for it. Similarly, here you choose data sets of a district and pay for the data on the parameters as you choose, such as income, education.”

This January, RajCOMP Info Services Limited (RISL) of department of IT invited seven corporations as eligible to bid for a five-year contract to build such an algorithmic system. Companies included IBM India, Accenture Solution, Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu, EY (Ernst & Young), Japan’s NEC’s India company, Coforge and Kyndryl. The project, called Services Management with Artificial Intelligence and Real Time System, or SMART, will begin in August.

As per the bid document, the government already collects in Jan Aadhaar information on 66 attributes (22 of them mandatorily) from residents – who their family members are, their income, expenditures. The companies are invited to use large-scale and interoperable databases, combining extensive data about residents held by 117 state departments to build their digital profiles, along with their profiles of their families and businesses.

The goal is that over time, this ML system will create the social welfare registry, such as the pensions list. These companies will match the given information on individuals and their families as per specific rules and thresholds to create profiles. The bid document states these “360 degree profiles” would become “golden records” on residents. It – without irony – states that data profiling will be used as the “single source of truth” on individuals.

Globally, experts say, questions remain over whether algorithms ought to be used in the welfare sector at all. ML AI has often been described as a kind of mathematical “black box” in which neither the developers nor the welfare recipients it was applied to can tell how it arrived at a decision. There have been multiple instances of what a recent MIT Tech Review news article described as “algorithmic misconduct”.

While the officials spoke of only auto-inclusion, publicly available bid documents state that Rajasthan wants to go further and use AI to remove the ineligible, determine eligibility criteria, and decide which documents are needed to prove eligibility. Further, over time SMART will start to use AI and predictive modelling for modifying the schemes as per budget constraints.

“The uses of AI, ML can take these functions well beyond what we have already achieved,” said a senior IT department official. “The government will have a clock running starting from everyone’s birth. When the resident become of age, such as if she turns 55 years old, she may not even have to apply and her pension would start on its own.”

When asked why the state government did not already do so, when it had all these data recorded and interlinked and already used it to remove beneficiaries, the official said that they did not consider their databases mature enough for auto-inclusion.

“We do not do so as of now because we can see there are many data upheavals,” said the official. “We can’t say with certainty for any beneficiary that this is exactly right, because the in-between link is the local e-mitra, who runs the village kiosk. The e-mitra has converted himself into an agent between the corrupt government servants and residents. For a mere Rs 500-1,000, he does anything for anyone.” As a way to fix this, the official, said the government would reduce the number of e-governance agents by less than one fourth of present, or hire fewer larger firms to manage e-governance.

A second way in which the state wants to use AI is to create a Rajasthan Data Exchange to share what it calls “non personal data” and make it available to start-ups, commercial enterprises, research institutions, said an official. Such data exchanges as policy were promoted by the union government in budget documents.

Shrinking space

Rights activists said that all these changes are occurring when programmes for individuals who society marginalises, such as these non-contributory pensions for the poorest from marginalised castes, remain as unpopular as before, portrayed as doles or freebies. Social security budgets are stagnant or reduced. The Union government uses 2001 census figures to determine beneficiaries, even as the number of people who needed it have grown.

Rizwan Ahmed of the Pension Parishad pointed out that this scheme is centrally sponsored, and state governments are supposed to match the Union government’s contribution. Between 2014 and 2025, the Union government’s allocation to the scheme reduced from Rs 10, 547 crore to Rs 9,562 crore, he noted.

In a period of over 100% inflation, central allocations were thus reduced in absolute terms and cut by more than half in real terms. It left state governments with a greater financial burden, even as the states are asked to demonstrate widespread use of digital tools and show savings. In the guise of administrative efficiency, state governments such as Rajasthan or Telangana then used software tools to further centralise power and cut back on welfare.

Rajasthan’s civil liberties and transparency activists warned that tech-solution ism has already devastated welfare in recent years, even as government’s and companies’ focus remained on just having more and more data on residents.

“Whether in name of Aadhaar or Jan Aadhaar or AI, it seems the aim is to remove all human intervention and to rely only on technology. It is an effort to evade accountability,” said Vineet Bhambhu, an engineer and transparency activist. “It seems the machine will decide – is this person who she says she is.”

Also Read: Tigray on the Brink: Ethiopia Faces Resurgence of Conflict as TPLF and Federal Tensions Rise