Rising Communal Tensions? Assam Government’s Actions Echo 1965 Anti-Muslim Sentiments

New Delhi: This past week, Assam chief minister Himanta Biswa Sarma had announced that his government would issue arms license to the “original inhabitants” and “indigenous” people residing in “vulnerable and remote areas” and those along the border with Bangladesh as a “deterrent to unlawful threats.”

Sarma’s announcement, made after a cabinet meeting on May 28, came as a bolt from the blue to many in that north-eastern state; was met with surprise, shock and criticism, both on social and news media.

Several in Assam have since expressed concern that it might push the state towards lawlessness, and mob justice. If law and order is handed over to the citizen by arming them, won’t it weaken the police, many has since asked? Is Assam Police under Sarma, who is also the home minister, losing control and common citizens have to be armed now for their own safety, some others have questioned.

In a poll bound-state, the Opposition parties are also calling the move of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government a shot at polarising voters to corner a victory because Sarma had categorically named five districts where the special scheme would be applicable.

A large swathe of the population in all those districts – Nagaon, Morigaon, Barpeta, Goalpara, Dhubri and South Salmara – belong to the Muslim community of East Bengal origin. The poll lens that Assam Opposition is using to interpret the announcement has only been plucked out of the trajectory Sarma has taken as a chief minister.

The communal trajectory

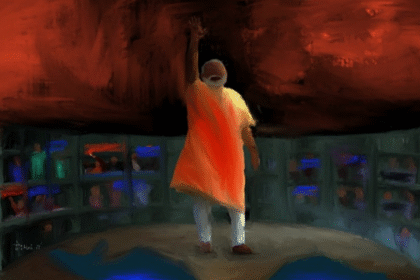

If we look at Sarma’s journey in politics in the last ten years, it is not difficult to understand that it has been designed around communal sentiments – be it delivering a fiery speech as a Congress leader in the Muslim-dominated areas of Assam in 2014 claiming that in Gujarat under Narendra Modi, the water taps carry the blood of Muslims (referred to the 2002 riots); or becoming a vocal proponent against that community after having jumped ship to the BJP.

If in 2014, he had to make that speech in the East Bengal origin Muslim-dominated areas of Assam against the BJP’s prime ministerial candidate to ensure that the community’s votes wouldn’t go to the All India United Democratic Front (AIUDF), now he has to continuously go after the same community so that the Assamese non-tribal and tribal votes don’t flip back to the Congress.

Since Sarma’s arrival in BJP, wherever a Congress MLA is seen strong, is soon ushered into the BJP. This trend has become so common that a large number of BJP MLAs and ministers today are former Congress leaders.

To stop that backward march of voters to the Congress in the 2026 assembly polls, the BJP government’s actions and Sarma’s public statements have progressively been directed at evoking that raw ‘anti-Bangladeshi’ sentiment of the majority community.

Once again, a version of the BJP’s 2016 campaign of ‘jati mati beti’ (community, land and identity) is clearly being worked at, knowing fully well that it usually gives result when Assamese and tribal identity politics are pitted against the common enemy – the Muslim of East Bengal origin.

An astute politician who has to be given credit for the ability to measure the pulse of Assam’s voters, Sarma is aware that the anti-incumbency against his government is on the rise in the state; and in order to keep the BJP’s 2021 voter percentage intact to return to power, he must continue to stick to that ‘anti-Bangladeshi’ sentiment.

It is not surprising then that in the recent weeks, Sarma hit out against Bangladesh’s caretaker chief Mohammad Yunus’ over-ambitious and irresponsible remarks at the strategic vulnerability of Northeast India even though external affairs and foreign policy is out of his government’s purview.

Equally not surprising when his government carried out the arrest of a journalist belonging to the East Bengal origin Muslim community. Sarma led it from the front; in a press meet held after his arrest in Guwahati, the chief minister accused him of belonging to the family of a ‘land grabber’, a term often used to identify the community in Assam since the British era.

The cabinet’s decision to issue arms licenses to a set of people living alongside people of East Bengal origin, was handled by Sarma himself at a press meet. Ditto when it came to implementing New Delhi’s ‘push-back’ strategy of ‘illegal immigrants from Bangladesh’.

Needless to say, this focused one-sided batting of Sarma is to overshadow his growing unpopularity among common people in the state due to allegations of nepotism and ‘land-grabbing’ against his immediate family; the ham-handedness of ministers seen close to him; and growing popularity of Gaurav Gogoi who has also recently been elevated to the post of state Congress chief.

But what must not be overlooked at the same time is a larger story around these developments.

India-Pak war of 1965

To comprehend the larger picture better, one must view some of these developments in conjunction, particularly the state cabinet’s nod to issue gun licenses to ‘original inhabitants’ in areas dominated by Muslims of East Bengal origin citing vulnerability in the border districts, and Sarma admitting that the ‘push back’ decision was at the behest of New Delhi.

These two developments in Assam then must be juxtaposed against the state government’s actions at the ask of New Delhi during and just after the India-Pakistan War of 1965.

Unlike 1971, Assam was not directly affected by the 1965 Indo-Pak war as it played out in the western frontier. Like in 1965, the state is also not directly affected by the post-Pahalgam skirmish with the neighbouring country. And yet, like we are seeing its effect on Assam politics and the government actions, in 1965 too, it had played out in a similar fashion.

Noted Assamese academic Monirul Hussain had highlighted in his critically acclaimed book The Assam Movement – Classes, ideology and Identity, that during the India-Pakistan War of 1965, though Assam was not directly affected, many Muslims from the state were pushed back into what was East Pakistan on suspicion of being infiltrators.

“A large number of Muslims including known Congressmen were arrested in the wake of the Indo-Pakistan War of 1965,” he had pointed out. The author had underlined that the government’s action had hugely ruptured the Hindu-Muslim relations in the border state.

Like it is now, that decision to ‘push-back’ people termed as infiltrators (now illegal immigrants) from East Pakistan (today Bangladesh) was also at the call of New Delhi.

Hussain had described how that push-back had played out in the society then: “First, many Assamese Hindus started to feel that their hidden fears of the Muslims of Assam working against the interests of the country were true, and second, at the same time, Muslims had the uneasy feeling that despite knowing their loyalty to India, their neighbours – the Asamiya Hindus did not protect them against such unwarranted arrests.”

If we place the current developments with those of 1965, we can only surmise that history may be repeating itself in Assam. Hussain had also stated that during 1965, the “alarm of a war-like situation” with Pakistan was “created by the Asamiya bourgeois press.”

“This was also carried to the floors of the state legislature. Some members repeatedly demanded expulsion of ‘lakhs’ of Pakistani infiltrators from Assam.”

Significantly, Hussain had held up that those repeated demands hinged on propaganda in Assamese media had led to the introduction of Prevention of Infiltration from Pakistan (PIP) scheme in the state. The statistical data published in his book of Nowgong (now Nagaon) district alone provided by the superintendent of police shows that as per that scheme in 1965, 20,189 persons were “forcibly deported to East Pakistan or pushed across the border.”

This time around, we see the government drawing legitimacy for the ‘push-back’ from a Supreme Court order.

After the 1965 war, Hussain pointed out that the fear against Muslims of East Bengal origin was found to be “not objective” and therefore, “the PIP scheme had to be abandoned.” The then chief minister B.P. Chaliha was on record having said on the floor of the house in 1969 that no more infiltrators were found in the border state.

When the India-Pakistan war broke out in 1971, the’ push-back’ was brought back but used only as a strategy to keep out Pakistani spies which was then a real fear.

Chinese Aggression of 1961

Prior to the 1965 ‘push-back’, Assam had seen a round of similar deportation carried out on sheer suspicion. It was in 1962, of people of Chinese origin living in Upper Assam, particularly in and around Makum town. Well-known Assamese writer Rita Chowdhury’s book Makam poignantly encapsulates those turbulent times.

The way geo-politics had played out in 1962, there was a strong sense in New Delhi that the Northeast would soon be captured by the Chinese. B.N. Mullick, who was the director of the Intelligence Bureau (IB) during the Chinese aggression, had written in his notable book, The Chinese Betrayal, that he had himself informed the then prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru on November 20, 1965 that “the Army headquarters was going to submit a plan that day to withdraw troops entirely from Assam and that this plan would be put up before the Cabinet at 3. p.m.”

Mullick was told of that plan by Army headquarters that morning and he also learnt that there was divided opinion about that plan. Nevertheless, it would be placed before the cabinet. An upset Mullick immediately went to Lal Bahadur Shastri who was then the home minister and told him to not support Army’s plan as he feared if a go ahead was given, the Chinese could come to North Bengal too.

Though Nehru is oft-accused by the BJP-RSS of abandoning Assam during the Chinese aggression, Mullick’s book has held up the fact that it was a thought that had sprung out of the Army headquarters, and not proposed by Nehru.

That development from 1962 is important now to also perhaps get a hold on the Assam cabinet’s May 28 decision to issue arms licence to the “indigenous” people. Though Sarma had explicitly said that the decision was made particularly “due to the recent developments in Bangladesh”, he didn’t (perhaps couldn’t) categorically say that it too was at the behest of New Delhi. Like he had said about the ‘push-back’ decision.

Mullick’s book stated that if the Army headquarters’ plan was to be approved by the Nehru cabinet, then he would resign as director, IB (DIB) and enter Assam “to organise a people’s resistance movement (against the Chinese) and not return till this area was reconquered for India.”

Nehru had approved of that idea in a conversation he had on November 20, 1965, noted Mullick, and also mentioned to him that Biju Patnaik had already approached him to go to Assam to organise a similar people’s resistance. Mullick agreed to take Patnaik on board. Together, they were to board a plane organised by the Air Force the next morning to execute the plan.

The duo did land up in Assam as planned the next morning but the plan remained unexecuted as the Chinese had announced ceasefire on the early morning of November 21.