Tariff Policy Changes Under Trump Expose India’s Structural Economic Vulnerabilities

Donald Trump’s latest tariff imposition along with an undisclosed penalty on India offers a critical mirror to the complex geopolitical landscape. The intricate and dynamic state of play marks a significant inflection point in the weakening of US-India bilateral relations.

United States’ recent imposition of a 25% tariff on Indian merchandise goods, effective August 1, 2025, is beyond mere commercial friction.

India now seems more alienated than ever before in the global geo-economic landscape, while facing higher protectionist measures from the US and that too at a time when its relationship with China, the other dominant world leader, remains troubled.

The unilateral tariff-action by Trump, who has now weaponised tariffs as a political leverage tool more than an economic measure seeks to achieve two-goals: create uninterrupted market access for US goods into the Indian market – which according to Trump currently face “obnoxious non-monetary trade barriers” – and de-link India’s growing and enduring trade and military ties with Russia (a point that has been made more strongly by other US Republican leaders in the recent past against India).

From India’s own perspective, its statements on not compromising its trade-position and policy preferences by giving away too much to American trade negotiators, while protecting its agriculture, dairy, and MSME sphere, offers strategic clarity. But at the same time, the current tariff imposition leaves India and Modi government on a vulnerable footing.

Questioning the ‘Goldilocks’ claim

A few weeks ago, India’s finance ministry declared the state of Indian economy to be in a “Goldilocks situation”, a rare alignment of moderate growth, subdued inflation and supportive monetary conditions.

Analysts too, taking a narrow, quarterly view of the Indian economy conceded, marking this as a “mini-Goldilocks moment” for its macroeconomic position, spurred by 7.6% GDP growth, peaking interest rates and stable corporate earnings.

A few other macroeconomic observers pointed out that India exiting FY 2024 with a $3.6 trillion economy and an underlying growth of over 7.6% projected a buoyant macroeconomic backdrop for 2025.

Yet beneath this overtly optimistic outlook is a more complex reality. More astute observers of the Indian economy with historical data, question this view which only disguises serious underlying structural imbalances.

Inflation

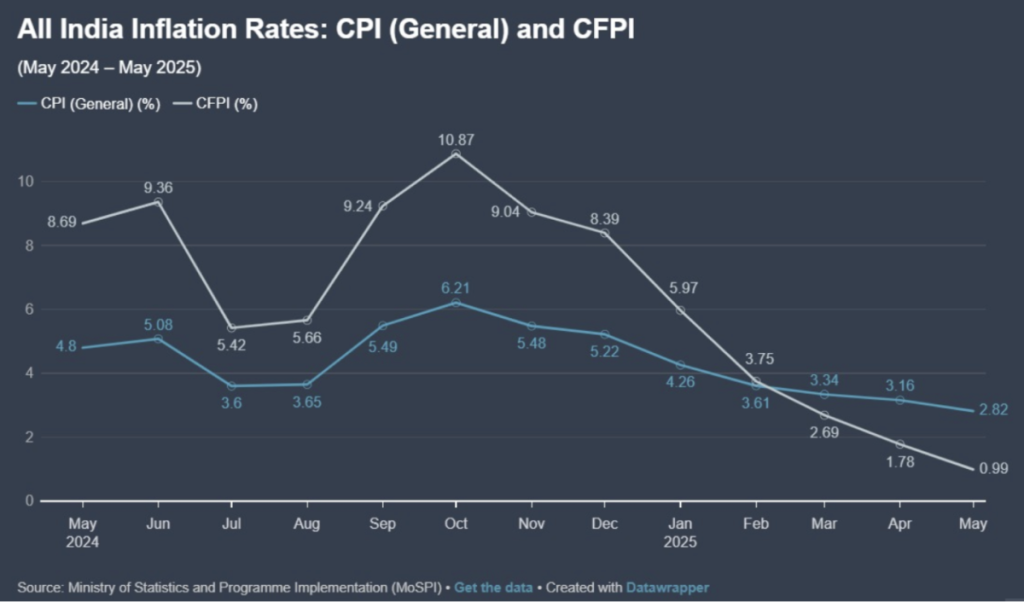

A closer look at the ‘All India Inflation Rates: CPI (General) and CFPI’ chart reveals a nuanced story behind headline price stability. While the CPI (General) indeed showed a commendable deceleration, falling from 4.8% in May 2024 to 2.82% by May 2025, hinting at inflation within the Reserve Bank of India’s comfort zone, the path to this point and the underlying dynamics, warrant significant scrutiny.

Throughout much of 2024, the Consumer Food Price Index (CFPI) consistently ran significantly higher than general inflation. For instance, in October 2024, when CPI (General) peaked at 6.21%, CFPI surged to an alarming 10.87%. Even in August 2024, with CPI at 3.65%, CFPI stood at 5.66%.

This persistent divergence is critical because food accounts for nearly half of the consumption basket for an average Indian household, particularly for lower-income groups. High and volatile food inflation, driven by factors like unseasonal rains, supply chain disruptions and global commodity price fluctuations, severely erodes the purchasing power of the common citizen.

Economists like Pronab Sen have argued that policymakers such as the RBI should focus on core inflation rather than headline CPI inflation, because core inflation excludes volatile food and fuel prices and better reflects the sustained burden of price increases across essentials like housing, education, transport, and personal care.

For an average family, the meaning of 10% food inflation is a direct and painful cut in real income, forcing them to either compromise on dietary quality, incur debt or drastically reduce other essential expenditures.

The eventual dip in CFPI to 0.99% by May 2025 (while welcome) must be viewed in the context of the preceding periods of severe pressure. The volatility itself creates uncertainty and hinders household budgeting and savings, directly countering the stability implied by a “Goldilocks” environment.

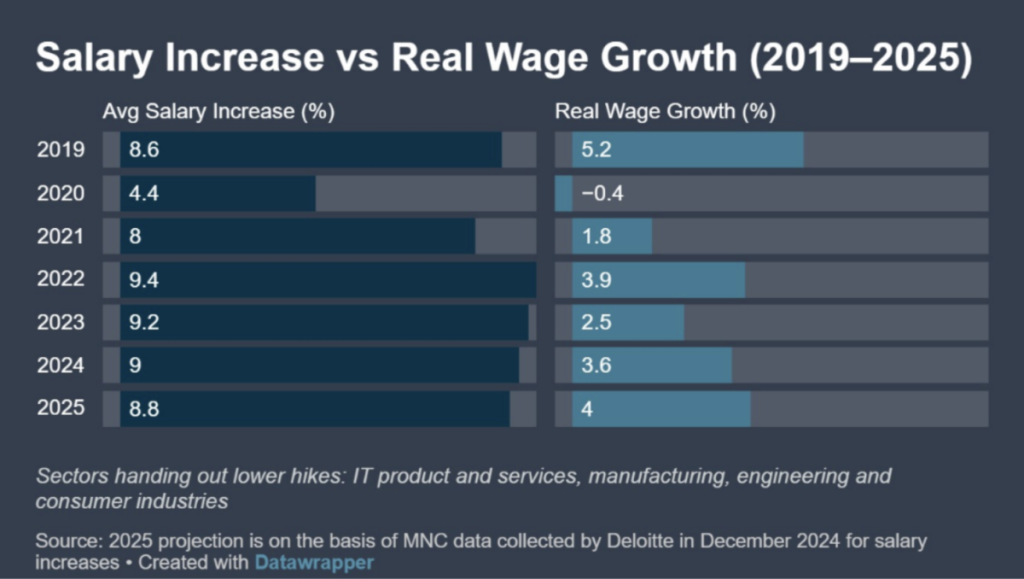

This inflationary pressure on essentials directly impacts the everyday reality captured in the “Salary Increase vs Real Wage Growth (2019-2025)” chart, which delivers one of the most compelling arguments against the “Goldilocks” perception. This data powerfully illustrates the chasm between nominal salary hikes and the actual improvement in purchasing power. For instance, in 2023, while the average salary increase was a respectable 9.2%, the real wage growth stood at a mere 2.5%.

Decline in real wage growth

More critically, in 2020, real wage growth turned negative, registering -0.4%, even as nominal salaries saw a 4.4% rise. Even the 2025 projection of 4% real wage growth against an 8.8% average salary increase indicates that half of the nominal gain is still being eroded by inflation.

This numerical gap translates into a tangible daily struggle. A 9% salary hike sounds promising, but if inflation is 7%, their actual ability to buy goods and services increases only by 2%.

This “silent squeeze” diminishes household savings, forces families to cut back on discretionary spending, and can lead to increased reliance on debt, particularly for those in sectors like IT product and services, manufacturing, engineering, and consumer industries, which are noted to be handing out lower hikes.

The International Labour Organization (ILO) and various labour economists have consistently pointed to challenges in job quality and stagnant real wages in many emerging economies, including India. Without substantial and sustained growth in real wages, the consumption demand, which is a critical driver for the Indian economy, remains constrained, undermining the foundations of a truly buoyant and broad-based economic recovery.

Unequal income distribution

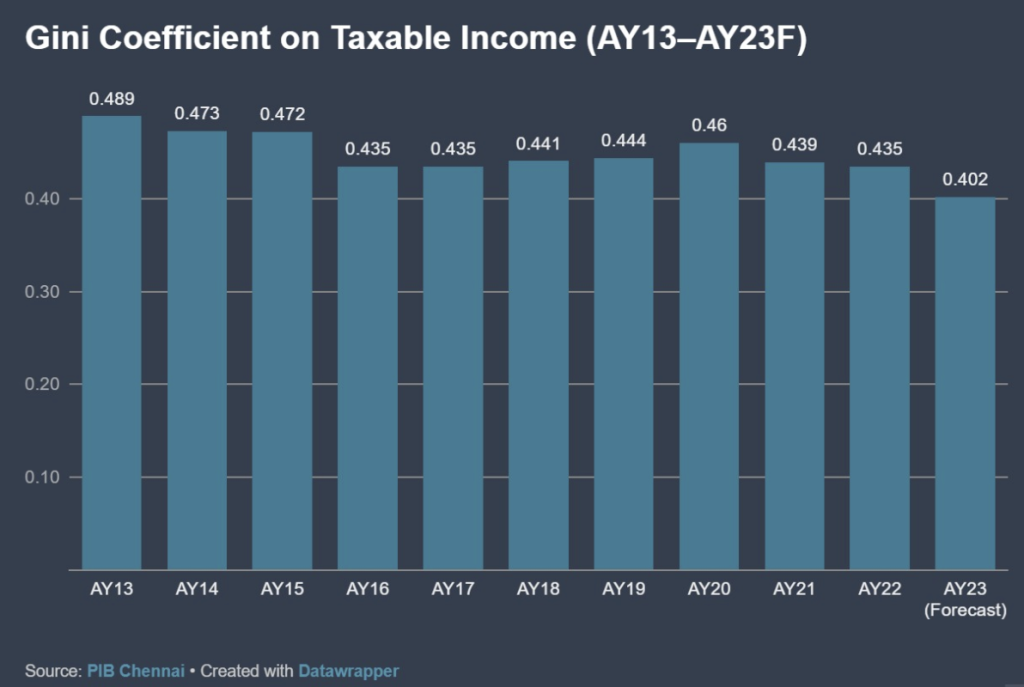

The unevenness in economic gains also finds reflection in the “Gini Coefficient on Taxable Income (AY13-AY23F)” chart, which offers a glimpse into income distribution. The Gini coefficient, a measure of inequality, shows fluctuations over the decade, starting at a high of 0.489 in AY13, dipping to 0.435 in AY16, and forecasted at 0.402 for AY23. While a declining Gini coefficient on taxable income might suggest some improvement, it is crucial to recognize the limitations.

Taxable income primarily captures the formal sector and those above a certain income threshold, potentially missing the vast informal sector and the broader distribution of wealth.

A recent essay by ORF authors Garima Nain and Ria Kasliwal describe India’s post‑pandemic economy as a multi‑speed or K‑shaped recovery, where certain segments, particularly the affluent and those in specific industries, thrive, while others lag.

While the number of billionaires in India has surged, real wages for many at the lower end of the income spectrum have struggled. This persistent inequality can undermine social cohesion, limit access to quality education and healthcare for a large segment of the population, and ultimately stifle long-term inclusive growth.

When a significant portion of the population feels left behind, despite robust GDP numbers, the notion of a universally beneficial “Goldilocks” state becomes deeply questionable.

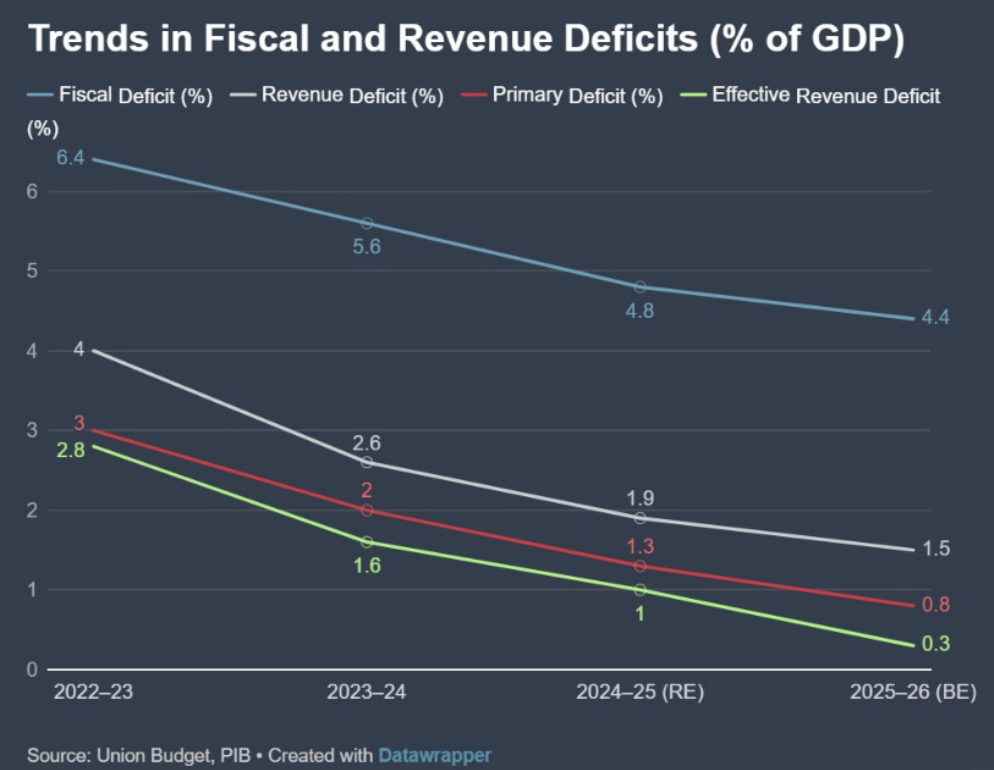

Adding to these domestic pressures, the “Trends in Fiscal and Revenue Deficits (% of GDP)” chart showcases the government’s fiscal position and its trajectory. While there’s a clear commitment to fiscal consolidation, with the Fiscal Deficit projected to decline from 6.4% in 2022-23 to 4.4% in 2025-26 (Budget Estimate), and the Revenue Deficit decreasing from 4% to 1.5% over the same period, the absolute levels of these deficits remain substantial.

The Primary Deficit, which indicates the current year’s borrowing excluding interest payments on past debt, is also projected to fall from 3% to 0.8%. However, for a developing economy like India, sustained high deficits can pose several macroeconomic challenges. They necessitate significant government borrowing, which can potentially crowd out private investment by increasing demand for funds and putting upward pressure on interest rates. This could deter private businesses from investing and expanding, thus limiting job creation and overall economic growth.

Furthermore, a high public debt-to-GDP ratio (which stood around 81% for the general government in 2022-23, significantly above the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management (FRBM) Act target of 60%) implies a substantial portion of future revenues will be diverted to servicing this debt. For the average citizen, this translates into reduced fiscal space for critical public spending on social sectors like education, healthcare, and infrastructure, or potentially higher taxes in the future to manage the debt burden.

Taken together, these critical indicators, volatile food inflation eroding purchasing power, persistent income disparities despite growth, stagnant real wages for the majority, and a tight fiscal space, paint a picture far more complex than the harmonious “Goldilocks” narrative suggests.

The perceived macro sweet spot, touted by some, is not universally experienced, and its underlying fragilities are becoming increasingly apparent.

The socio-economic realities on the ground, consistently analysed by a broad spectrum of economists, reveal that the journey towards inclusive and sustainable prosperity for all Indians remains an uphill climb. Indeed, for those willing to look beyond the headlines and delve into the granular data, the myth of the macro sweet spot is cracking open.

Assessing the potential impact of tariffs in exposing structural risks

India’s growth picture rarely emerges from its exports. It imports way more that what it exports and has had a surplus of trade with US merely for skilled-human capital mobility reasons.

With India’s goods trade with the US totalling approximately $129 billion in 2024 and a rising trade deficit on India’s side, the new tariffs represent a notable external shock for trade-focused sectors too apart from the short-term effects of this on India’s rupee value and foreign investment position.

Beyond the immediate impact on merchandise trade, any ripple effects of these tariffs, once into effect, may extend across broader macroeconomic terrain, influencing investor sentiment, rupee valuation, and GDP forecasts.

More than that, India’s weak export competitiveness across sectors at a broader level might be acutely challenged over the coming months, and these rising trade barriers are expected to contribute to persistent depreciation pressure on the rupee.

The Indian rupee recently dropped close to Rs 87 against the US dollar, triggering Reserve Bank of India (RBI) intervention to stabilise markets. Despite such intervention, analysts often view the rupee as overvalued by approximately 8%, a factor limiting export competitiveness.

While central bank intervention is anticipated to continue, it may not necessarily provide strong appreciation support. India has judiciously spent tens of billions in reserves (e.g., net purchases of $1.7 billion) to smooth volatility.

Furthermore, the broader political friction, linked to US concerns over India’s enduring ties with Russia and its “Make in India” policies, compounds risk to the bilateral relationship, which one can see as the more serious collateral damage of the latest tariff announcement.

It represents a low-point in Trump-Modi’s projected ‘friendship’ at a time when the Indian government is being questioned in the Monsoon Session of the Parliament over the role of the US, as claimed by Trump repeatedly, in the recent India-Pakistan conflict.

No trade partnership with the US and a less-entwined American bond will further alienate India and its ‘Vishwaguru’ ambitions even more, given its preexisting troubles with China at the border, at a time when both the US and China are emerging as dominant anchors in an increasingly bi-polar world order.

India’s own economic weaknesses and relatively low export-competitiveness level across sectors, driven by a low private investment-growth position, present little opportunity for it to carve a niche for itself, while trying to diversify partnerships, and seek favourable terms of trade in FTAs with the EU, UK and other critical trade partners.

At a time when consumption demand is low, jobless growth position continues to expand while inequality rises, India seems to offer little in its bargaining chips beyond an ‘enormous market size’, which is less appealing to those seeking greater trade with a sound macro-economically positioned partner.

India’s economic liberalisation history is also triggered by crisis episodes of 1991 and the 1998 sanctions, suggesting a historical precedent for transforming adversity into an opportunity. A potential disruption with the American government may offer a strategic opportunity for structural adaptation and enhanced resilience, forcing a critical re-evaluation of existing vulnerabilities and forging pathways to greater self-reliance. The will, however, to do so at a large level, appears weak in the current Modi government, which is more obsessed in securing power at all costs than in engaging meaningful economic reform.