Union Govt’s U-Turn on Online Money Gaming Sparks Industry Shock and Policy Reversal

Bangalore: As this article gets written, India’s online money gaming industry has been sandbagged.

Late last week, after President Draupadi Murmu gave her assent, the Promotion and Regulation of Online Gaming Bill became law. With that, India’s booming fantasy sports market, where people put real money on players’ on-field performances, was summarily outlawed.

The Bill didn’t just take industry executives by surprise – it also clashed with the Narendra Modi government’s previous statements on online gaming. Just last July, it was examining a proposal from the Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade to help real money gaming firms draw global investors by exempting 100% FDI from official approvals. This May, the Modi sarkar defended its imposition of 28% GST on the industry before the Supreme Court.

The industry itself was seeking tax relief — and its own sectoral regulator.

There was little sign, in effect, that a ban was coming. As an unidentified executive, described by The Times of India as a top official in one of the bigger gaming companies, told the daily: “What is surprising is that, while (the government) regularly consulted us on most of the issues, there was virtually no discussion this time around on a proposal that has the capacity to decimate us.”

As with most government decisions, this one comes with large fallouts. Quick-takes – like the ban’s impact on gaming companies and their employees or what it will mean for the government’s GST revenues — miss the role these apps have come to play in poorer Indians’ lives.

Much has been written about how India’s small businessmen, in the wake of dropping revenues, switched to stock trading in the hope of higher returns. Similarly, crores of Indians (especially those from poorer families), faced with dwindling opportunities but aided by the spread of UPI, cheap smartphones, cheaper data and familiarity with games like cricket, have turned to online real money games. Some were betting real money on casino games like poker or rummy, while a large chunk of the market slipped into fantasy sports around real world matches, mostly cricket.

Before a match begins, they place a wager on the 11 players who will perform best. Once it ends, gaming firms award points based on how these players performed and a part of the pool — all the money collected as wagers — flows back as winnings. In effect, instead of betting on companies, they bet on players. “It is like day-trading now,” an official at the Federation of Indian Fantasy Sports (FIFS) said on the condition of anonymity. “I was in a village where the help used to vanish at 7 pm. He was choosing his team. Someone in a nearby village had made Rs 45 lakh. And now everyone else is trying too.”

Despite its scale, implications (poorer Indians seeing speculation as their best hope of riches) and media reportage (see this, this, this and this), the industry escaped critical attention. According to FIFS, about 22.5 crore Indians have downloaded fantasy sports apps. Of these, 85% (a little over 19 crore) bet only on real cricket games. That is close to one-seventh of India’s total population — and almost one-fourth of all Indians below 30 years. During the Indian Premier League, participation is said to rise as high as 37 crore.

Most of these participants are cash-strapped. As a 2019 KPMG report found, 40% of people earning under Rs 3 lakh per year play fantasy sports five or more times a week, while only 12% of those earning over Rs 10 lakh per year do so.

Given the odds against winning, most of them made a net loss but, between addictive algorithms, prizes that went as high as Rs 2.02 crore, and no other conceivable way to make money, persisted. The industry they fed grew by leaps and bounds. Back in 2023, a private sector cricket broadcaster in Mumbai pegged the volume of bets at Rs 3,00,000 to Rs 4,00,000 crore (it is higher now).

Along the way, the economics of India’s consumer market and sports (especially cricket) have changed as well, with other attendant consequences.

We should start at the beginning.

UPI, cheap smartphones and cheaper data

The forerunner of Dream11 and its ilk was a well-intentioned show on ESPN called Super Selector. Broadcast around 2002-03, with the intent of boosting interest in non-India matches, it wanted viewers to log into the ESPN website and announce their playing 11. They couldn’t put in money but there were prizes.

It was a time when PC penetration was low. “Even so, demand was so high that the server couldn’t take the load,” said a former executive at ESPN, on the condition of anonymity. In the years that followed, India saw other attempts but those didn’t go anywhere either. Even Dream11, founded in 2008, had a slow start.

It started to make money only around 2015-16. One trigger was the launch of UPI in 2016. “Few people know how to link bank accounts to these platforms,” the executive had said. “Even fewer had credit cards. The growth of Dream11 was unleashed by UPI.”

In tandem, the company also brought in smaller wagers. “Unlike the UK, where people play over a season, you could play here for just a day,” added the FIFS official. “You could also wager smaller sums — not just Rs 1,000 but also Rs 50 or Rs 11. This was sachet pricing. Between that and rising phone and data usage, the number of participants grew. The business expanded into semi-rural and rural markets as well.”

Back in 2023, when this reporter began studying these transformations, he was told the business model here is similar to that of the lottery business, where much of the pool goes back as winnings. If, before a match, one lakh people paid Rs 50 apiece and chose their dream team, Dream11’s total collection would be Rs 50 lakh. “Of this, it would retain 15% as its fees, pay 18% from there as tax (Rs 1,35,000), and hand back the remaining Rs 42,50,000 as winnings,” said the FIFS official.

This money could go back to as many as 80% of participants. “The winner might get 15% of the pool,” the ex-ESPN executive had said. “The runner-up might get 10% of the pool. In all, 80% of the players will get something — Rs 30, Rs 40, Rs 45.” Small losses, he said, are more addictive. “They ensure better retention.”

Further addiction came from ads saying an investment of Rs 39 might yield Rs 1 crore. And, as this reporter was told, from algorithms which could spot slackening users and direct some winnings to them. “The algos are a mystery to everyone,” the broadcaster had said.

Dream11 was asked to comment on the charge that real money gaming is pushing poorer Indians into gaming disorders and that its algorithm can spot slackening users. The firm didn’t respond to the specific questions but shared a statement: “Dream11 has always followed and will continue to follow the law — in letter and spirit. While this change in law has resulted in a loss of approximately 95% of our group’s revenue, we remain committed to building a great Indian sports company, driven by AI and the creator economy.”

The Online Gaming Bill, however, alludes to“serious social, financial, psychological and public health harms” from online money games which, as it adds, “use manipulative design features, addictive algorithms, bots and undisclosed agents, undermining fairness, transparency and user protection (and) promoting compulsive behaviour leading to financial ruin”.

Three years after UPI’s introduction, Dream11’s valuation had crossed $1 billion. It was India’s first gaming unicorn. Seeing its success, others came in. “This is not a business with high entry costs,” the FIFS official had said. “For a crore of rupees, I can start my own fantasy sports app.”

Some, like Mobile Premier League and My11Circle, started with cricket. Thereafter, as these firms came to dominate fantasy cricket, others diversified into games like Rummy, Ludo and Poker. Over time, even Dream11, My11Circle and Mobile Premier League diversified into other sports, including football, volleyball and kabaddi.

In 2021, just three years after its inception, Mobile Premier League too became a unicorn. Six months later, Games24X7, which owns My11Circle and RummyCircle, followed suit.

How cricket changed

Along the way, as with stock market derivatives, the amount of money riding on each match surged well past its on-field cash value.

Take cricket. At one time, bodies like the BCCI made money off ticket sales and stadium advertisements. Then came Mark Mascarenhas and the telecast rights boom. In 2023, for instance, Disney-Star acquired four-year rights to broadcast ICC events in India after bidding just over Rs 25,500 crore.

With online money gaming, the amount of money riding on each match spiked yet again. For most Indians, the first inkling of the sheer volume flowing into these firms came from tax notices. After securing a court order that classified online money gaming as a game of skill, the industry was paying 18% tax on the 15% it retained as earnings — compared to games of chance, which are taxed at 28%.

The Directorate General of GST Intelligence, however, took a stricter stance. It demanded 28% tax on the total value of bets placed, rather than on retained earnings, raising a massive tax demand of Rs 1.12 lakh crore against 71 online gaming companies for FY22-23 and half of FY23-24. This reflected a betting pool of Rs 4,00,000 crore (over 1.5 years) across those firms, in a sector now estimated to include 400 companies with an annual growth rate of nearly 28%.

As it swelled, this firehose of cash changed cricket itself.

App-users could wager only on the days matches were being played. To get around this, as a former member of the BCCI told this reporter, online money platforms began sponsoring league tournaments at cricket associations – in both the Indian hinterland and overseas.

Most of these were simulacrums of IPL. Unlike it, however, most didn’t make money. “In IPL, the cost of a team is Rs 7,000 crore-Rs 8,000 crore,” the FIFS official said. “Promoters make about Rs 350 crore to Rs 400 crore each year as their share of IPL revenues and another Rs 200 crore-Rs 250 crore as advertising. Which means they recover their investment in about ten years.”

In contrast, state league teams are much cheaper – about Rs 3 crore-Rs 4 crore. Most of the time, owners don’t recover this money. “Advertising barely covers players’ costs,” the FIFS official said. “They sometimes make money trading teams or content themselves with bragging rights.” Some, as the former member of the BCCI said, even tried to bet on these matches, deriving additional insight into each match given their team ownership.

What is more incontrovertible is that India began to see more cricket matches. On the day we met, the FIFS official rattled off the names of ten league tournaments and said: “Most of these were not around five years ago.”

With all this, as the firehose thickened further, firms in the betting sector began to feel the pinch.

New enemies

Online real money gaming firms had benefitted from a 2017 Punjab and Haryana high court order which ruled that fantasy cricket, requiring knowledge of the game, was a game of skill, not chance.

This distinction was material. Not only did games of skill pay lower GST (18%) than games of chance (28%), the order was also expected to distance the sector from gambling and reduce political risk. Nonetheless, it was a polarising order. “The difference between skill and luck is whether you can repeat your performance,” said the head of a Mumbai-based investment fund. “If you cannot, this is not skill.”

Even as the industry dug moats, a new challenge came from elsewhere. “Once Dream11, etc, started, the lottery business began to fall,” said the Mumbai-based broadcaster. “This is not a surprise. It is the same fix – the lure of cash rewards but in the shape of cricket, which makes for better engagement. People running state lotteries got hammered.” So did operators in India’s informal satta markets.

At this time, India saw two coincidences. Santiago Martin, described as India’s lottery king, had made headlines in 2024 for buying the most electoral bonds. Of the Rs 1,368 crore worth of bonds he bought, Rs 509 crore went to DMK between April 2019 and January 2024. In 2022, the DMK government promulgated the Tamil Nadu Prohibition of Online Gambling and Regulation of Online Games Ordinance, a bill which then ran afoul of governor R.N. Ravi, who held his own consultation with gaming industry executives and sent it back.

Martin also sent Rs 100 crore to the Bharatiya Janata Party between October 2021 and January 2022. A little over a year later, the online money gaming industry received a bodyblow. Online games, skill-based or chance-based, were placed in the 28% GST slab in the 50th GST meeting in July 2023. Compounding matters, as the FIFS official said, this 28% would be levied each time users bid – at the point of entry. “So Rs 100 becomes Rs 72 after paying Rs 28 to the government,” he said.

The Wire wrote to Martin asking him to comment on industry speculation that a quid pro quo had taken place. We had not received a response by the time this article was published. It will be updated when he responds.

What is more incontrovertible is that, in October 2023, retrospective GST notices went out. Even as firms fought these notices, the sector began to see consolidation. “Dream11 began paying that Rs 28 out of its pocket,” the FIFS official said. “Users will bet multiple times, adding to their pool whenever needed. Making 15% off each of these transactions, Dream11 figured it could recover that 28%.”

Smaller firms, however, could not subsidise participants. With that, users began switching less between apps. “Just 42% reported revenue growth following the GST amendment,” reported Economic Times. “This represents a notable shift from the industry’s prior trend of exponential growth.” Even firms like Mobile Premier League downsized.

There were yet other headwinds. Fear that the Punjab and Haryana order might get overturned, however, had persisted. “If it is overturned, this industry will close,” the broadcaster had said. “Which is why investors are staying away.” In response, as this article said above, the Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade pushed a proposal to help the industry draw global investors by exempting 100% FDI from official approvals.

Through these troubles, money kept flowing in. Projections for 2033 placed its size at a whopping Rs 34,66,130 crore. Drawn by such numbers, global betting firms like DafaBet and DafaNews began sponsoring league matches as well. DafaNews, for instance, sponsors Salem Spartans, a franchise in the Tamil Nadu premier league. “In countries with legalised betting, you have firms like Bet365 etc,” the Mumbai-based broadcaster had said. “DafaNews works in countries where betting is not allowed.”

With that, India’s speculation economy around cricket came to stand on three pillars — fantasy sports; firms like DafaBet; and local bookies. All of them hoovered up money from the hinterland and moved it to a few. As this report published last year in Scroll says: “In 2024 betting apps (were) projected to earn an average revenue of $292 (around Rs 24,000) from every user.”

With that, not only did India’s consumption economy take a pounding, Indians slipped into addiction and paid large costs, as the video below shows.

Endgame

It’s against this backdrop that the Bill has to be seen.

For now, apps have halted operations. Dream11‘s homepage says: “As per The Promotion and Regulation of Online Gaming Bill, 2025, cash games and contests have been discontinued on Dream11.” Mobile Premier League’s homepage is no different. Lawyers are proposing legal challenges saying, among other things, that the Bill fails to distinguish between games of chance and games of skill.

In its statement, however, the firm said it will “sharpen our focus on scaling our other Dream Sports portfolio companies, namely FanCode, DreamSetGo, Dream Game Studios, and Dream Money, as part of our mission to ‘Make Sports Better’. Some of this has been reported by newspapers. Dream Money, for instance, is a personal money management app which will allow investors to invest in gold, fixed deposits and SIPs — a move that suggests it will pivot away from its core users.

The costs that follow run significantly beyond the travails of these firms. Within cricket, sponsorship for tournaments is drying up – with attendant implications for local cricket players. Revenues of firms offering UPI payment services will be hit as well. The government’s about-turn itself remains puzzling – in part because the Lok Sabha passed the Bill after seven minutes of discussion. The next day, the Rajya Sabha did so without any discussion whatsoever.

long the way, the opportunity costs of its delay went unexamined.

Over the last ten years, tens of thousands of crores slipped out of consumer markets, dropping instead into gaming apps. Even more seriously, India’s poorer youngsters, in the grip of joblessness, came to believe that speculation is their best bet for multi-bagger returns.

Between the middle-class’ rush into stocks and poorer Indians’ beeline for real money gaming apps, India became a land of speculators.

What happens next is unclear.

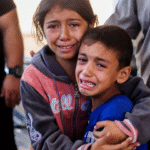

Also Read: Gaza Crisis: Save the Children Warns Thousands of Kids Too Malnourished to Cry Amid Ongoing War