Vantara’s Release of Spotted Deer in Banni Raises Ethical and Scientific Concerns

Bengaluru: On July 15, Reliance-owned Vantara – which runs a rescue centre and zoo, and calls itself an organisation that undertakes ‘conservation’-related activities – in collaboration with the Gujarat Forest Department released 20 spotted deer in a 70-hectare area in the Banni grasslands in Gujarat.

Banni is a semi-arid desert ecosystem spanning around 2,600 square kilometre in Kutch in northwestern Gujarat. It is home to mostly grasses and shrubs. Herbivores such as nilgai, chinkara (or the Indian gazelle) and blackbuck dwell here.But Banni isn’t home to spotted deer.

Ecologists familiar with the Banni landscape said that spotted deer are not naturally found in Banni and releasing them in the area needed more thought and there are several reasons why. Firstly, the deer will not be able to survive the harsh heat of the Banni grasslands. Secondly, if the deer do survive, they could impact the ecosystem. They said that it appears that authorities are setting the stage to introduce African cheetahs in Banni by introducing spotted deer so that the cheetahs have prey to live on.

Spotted deer released in Banni

In a social media post titled “Protecting Biodiversity in Banni” on July 15, Vantara (which runs the Greens Zoological, Rescue and Rehabilitation Centre in Jamnagar in Gujarat) said that in a collaboration with the state forest department, it had released 20 spotted deer or chital in a specially-designated 70-hectare area in the Banni grasslands of the state.

According to a statement on the Vantara website, the joint project “aims to restore and strengthen the biodiversity of one of Asia’s largest and most ecologically important grasslands”.

This “major step” marks a “significant milestone” as it also “reflects a growing synergy between government-led conservation goals and private-sector expertise”, it added.

“This project showcases how partnerships based on shared conservation goals can lead to meaningful outcomes,” Brij Kishor Gupta, director of GZRRC said in a statement. “By combining scientific expertise with logistical support, we aim to strengthen biodiversity in Banni while contributing to government-led efforts.”

According to Vantara, its teams along with the Gujarat Forest Department conducted a joint field assessment before the release, “to evaluate habitat suitability for the deer and to identify key ecological factors for the long-term success of the species”. This assessment has also helped develop “an informed plan to ensure the deer would thrive in the new environment”, per the statement.

Vantara’s widely read post on Instagram said that “habitat checks, expert teams, and custom transport ensured a smooth rewilding process”.

Posters on the cages containing the spotted deer read “Rewild India, An Initiative by Vantara”.

“Rewilding” is the process of bringing back an ecosystem to its natural state, usually by re-introducing species that may have gone extinct but once lived there.

Hot Banni not home to spotted deer

However, spotted deer do not naturally occur in Banni.

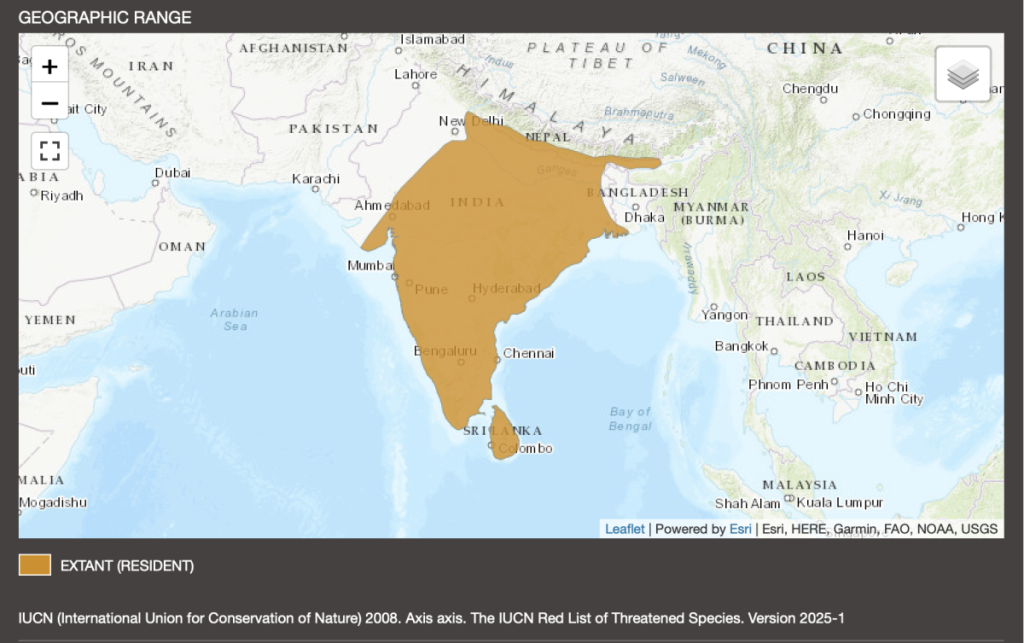

The distribution map for spotted deer in the book “A Field Guide to Indian Mammals” authored by conservationist Vivek Menon excludes the Banni area in Gujarat. The distribution map for the species in the IUCN Red List also excludes Banni.

Two ecologists who are familiar with the Banni grasslands also said that spotted deer do not naturally occur in Banni because of the hot, semi-arid, desert-like nature of the landscape.

“In my years in Banni, I have never seen a spotted deer there nor found any evidence of its existence,” political ecologist Ovee Thorat said.

Thorat worked in Banni from 2013 to 2019, studying the history of interventions (for conservation and development of Banni) in the landscape and their outcomes, as well as grasses and ecology.

“Banni is a semi arid, highly stochastic system characterised by droughts and floods. In no way can a species such as spotted deer that is known to depend on year-round fodder and water availability survive here without constant and intrusive or heavy handed management,” she said.

Another ecologist who is familiar with the Banni landscape but did not want to be named said that the introduced spotted deer would not survive the harsh, hot summer of Banni, when the semi-arid desert environment touches temperatures of 50° Celsius.

“They will not survive,” the ecologist cautioned. “Deer cannot survive in such hot environments. Sure, spotted deer do occur in hot regions such as Sariska and Ranthambore in Rajasthan, but there they can take cover under trees and there are still water sources they can depend on.”

But what if authorities provide shade, food and water, and help the spotted deer survive the Banni heat? Then there’s another worry: invasion. Thorat pointed out how spotted deer are now an invasive species in the Andaman Islands. The British introduced a few animals here in the early 1900s. But biologists now consider it an invasive species, as its numbers have increased. Spotted deer are also invasive in many parts of the world. For instance, spotted deer populations in some protected areas in Argentina have increased so much that they are permitted to be culled.

“All of this [introducing spotted deer in Banni] feels like a repeat of colonial practices that ignored the violation of complex ecologies and cultures,” Thorat added. “What is that part of Banni going to be if not a highly managed zoo? What about unaddressed issues of rights of the communities dependent on this land? If this is what we call “rewilding”, where is the science and ethics?”

And local communities in Banni are highly dependent on the grasslands here. The Maldharis, a semi-nomadic indigenous community live in Banni. The large, open grassland expanses in Banni are crucial grazing pastures for their livestock, which the Maldharis depend on for their livelihoods.

Cascades, other contenders and cheetahs

“The introduction of spotted deer into the Banni ecosystem is not just a relocation – it is a milestone in ecological restoration. Deer play a critical role in the food chain and help in maintaining the balance of herbivore and carnivore populations. Their presence also encourages the growth of native plant species by acting as natural grazers. Over time, this contributes to the regeneration of local grassland ecology and strengthens the overall health of the habitat,” Vantara’s website read.

Vantara is right: deer are crucial components of ecosystems. But this is not a blanket rule: it is highly context- and species-specific. Studies such as this one show that grazing by deer can also flip the balance the other way, including by increasing the abundance of exotic plants. In India’s very own Andaman islands, ecologists found in 2013 that areas inhabited by spotted deer – an introduced species in the islands – showed faster rates of forest degradation than areas without them.

Introduced species tend to have “cascade effects”, Thorat said. Cascade effects are ecological changes that can happen when one component of a food web is altered. Introducing spotted deer in Banni, for instance, could lead to changes in plant composition in the grasslands, Thorat said.

How does that work?

Just like people have food preferences, some herbivore species tend to favor specific types of plants or grasses for foraging. Introducing a new species of herbivore into an ecosystem can reduce the availability of these preferred plants for other native animals, disrupting the delicate ecological balance that exists in the area.

Such imbalances can have ripple effects across different animal groups. For example, a 2015 study found that the introduction of spotted deer in the Andaman Islands led to a reduction in understory plants—small vegetation growing beneath larger trees. This shift in plant structure caused a five-fold decline in forest floor and semi-arboreal lizard species, showing how the deer’s presence had a cascading impact on an entirely different taxa.

If spotted deer were to increase in number in Banni and take over larger parts of the grassland, the changes in plant composition may affect the already-meagre population of chinkara or Indian gazelle in the area, Thorat said.

“The deer could also compete with other smaller species that depend on grasses such as lizards, small mammals,” she added.

If authorities wanted to really rewild the Banni grasslands, there was another, more apt contender for reintroduction: the blackbuck, a species that used to thrive in Banni. Releasing blackbucks would have been a better and more scientific move because the species once occurred in fair numbers in the grasslands but don’t anymore due to poaching, said the ecologist who did not want to be named.

“It just looks like the stage is being set for the introduction of African cheetahs in Banni,” the ecologist added.

That’s because authorities have been trying to do exactly this – bring in spotted deer from other protected areas – into Madhya Pradesh’s Kuno National Park where India’s ambitious African cheetah introduction programme is underway, as prey for the cheetahs there. In October 2024, a senior park official told the Free Press Journal that they had “demanded” 500 spotted deer each from Kanha, Bandhavgarh and Madhav National Parks, and that Kuno had already received some from Pench and Kanha.

Plans are afoot to introduce African cheetahs from their current homes in Madhya Pradesh into Banni, according to news reports. In fact, a day after Vantara and the Gujarat Forest Department released the spotted deer in Banni, Gujarat’s top forest official told PTI that Banni was ready for the cheetahs. Jaipal Singh, the Principal Chief Conservator of Forests (Wildlife), Gujarat, told PTI that a 600-hectare area in the Banni grasslands has been set aside for the cheetahs. A breeding centre is already set up here, and efforts are underway to “further enhance the prey population of chital and sambar”, he added.

A move like introducing spotted deer in Banni required more thought, application of science and ethics, the ecologists said.

“If anything, a step like this requires critical thinking and caution and not celebration,” Thorat said.

Also Read: Poll Numbers Plunge as Trump’s Connections to Powell and Epstein Resurface