Why Indian Rivers Deserve Legal Rights to Ensure Their Protection and Survival

As North Eastern states experience disasters under flooding, rivers wreaking havoc, parts of the country also see an extreme season with the drying of its rivers having adversarial impact on soil, agriculture, and livelihoods of millions on depend upon it. Rivers and their critical vitality in shaping, managing and nurturing livelihoods have captured imagination of writers, artists, and scholars for centuries.

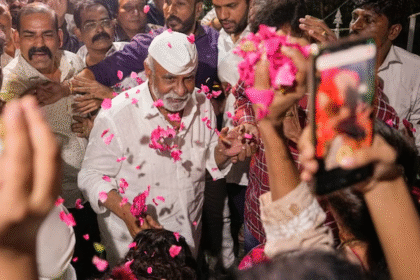

In the ancient Hindu imagination, the Ganga is not a river. She is a mother. A bearer of life. A witness to history. For thousands of years, poets, priests, and pilgrims have also knelt at her banks, offering flowers and ashes alike.

But in the courtroom, such reverence has not translated into responsibility. For Indian rivers today, personhood is poetry – but not yet law.

And yet, the idea is not as far-fetched as it once seemed.

If the river has a legal standing in a court of law

In 2017, the Uttarakhand High Court declared the Ganga and Yamuna “living entities” with the rights of a legal person.

For a brief moment, the river had standing in a court of law.

It could, in theory, sue a polluter, resist a dam, or demand its flow be restored. But the decision was swiftly stayed by the Supreme Court, citing practical difficulties: Who would represent the river? Who would be liable if the river “committed” harm, like flooding? The Ganga returned to her pre-modern role: sacred but silent.

Eight years later, in 2025, the waters are rising again – this time not just in volume, but in voice.

Earlier this year, Rajya Sabha MP Satnam Singh Sandhu too introduced a bill proposing that Indian rivers be granted legal personhood through statute. In a nation where rivers are worshipped yet routinely strangled by concrete and sewage, the symbolism is powerful. But what matters more is the potential shift in power: from human dominion to ecological dignity.

We have reached the limits of technocratic solutions to ecological collapse.

India’s flagship Namami Gange mission, launched with fanfare by the PM in 2014, has spent tens of thousands of crores and built miles of sewage infrastructure.

Yet, the state of the Yamuna river – an important tributary of Ganga – in Delhi remains a chemical soup, where, fish die-offs are routine, and residents routinely gag at its banks. No amount of money can save a river if its right to flow, breathe, and exist is not recognized in law.

In February, a Supreme Court-appointed committee reported that illegal embankments had been constructed through Kalesar National Park, obstructing the Yamuna’s natural flow. On paper, it was a clear violation of forest and water laws. But the implications ran deeper.

These embankments were not just environmental infractions – they were symbolic of a larger rupture: the quiet, everyday mutilation of riverine systems under the guise of “development.” When a river’s path is bent without its consent, it is not merely diverted; it is disenfranchised.

Climate activist Ridhima Pandey, who first came into national consciousness for suing the government over climate inaction stood against the Kalasa-Banduri diversion project in Karnataka. Her protest was against a legal structure that treats rivers as passive infrastructure rather than living systems with embedded rights.

Not isolated acts of environmental negligence but democratic failures in slow motion

These are not isolated acts of environmental negligence. They are democratic failures in slow motion. Rivers may not cast votes, but they irrigate the very geographies our electoral maps are drawn on. To exclude them from legal personhood is to ignore that their depletion undermines the people who depend on them and the constitutional promises made to those people.

Critics scoff. They warn of legal absurdities.

Who defends the river in court? Can a river own property? The answer lies not in abandoning the project but in refining it. Guardianship models – where citizens, tribal councils, or environmental boards act as legal stewards – have worked elsewhere. In New Zealand, Maori iwi serve as co-guardians. India, too, can empower communities that have lived with and for rivers, rather than outsourcing custodianship to bureaucratic boards 500 kilometers away.

It is a reckoning with the doctrine of human supremacy. Our legal system, forged in colonial logic, sees rivers as resources, not relationships. They are either dams to be built or drains to be dredged. But this worldview has failed us. Climate change is not just an engineering challenge; it is a civilisational crisis. The law must evolve.

To grant rivers rights is not to anthropomorphise them, but to decolonise the way we see the world. This is critical for their being and sustenance through a realisation, recognition of rights that matter.

The Ganga, after all, has outlived empires. She will likely outlast this one too. But what shape will she take – choked and canalised, or flowing freely as a subject of law and reverence? Personhood is not a silver bullet. But it is a beginning. A way of saying: the river has been speaking all along. It’s time we learned how to listen.